Wendell Phillips on a platform,” wrote Henry Adams in his Education, “was a model dangerous for youth.” In this opinion Adams was not alone among the descendants of New England’s colonial aristocracy. Phillips was Beacon Hill’s premier renegade. Cousin to half the Brahminate, from Oliver Wendell Holmes to Phillips Brooks, he threw over his privileged inheritance to devote his life to social reform as a tireless agitator for the most radical and unpopular causes of his time. So effective was he that an 1867 newspaper editorial pronounced him “the man who as a private citizen, has exercised a greater influence upon the destinies of this country than any public man of his age.”

|

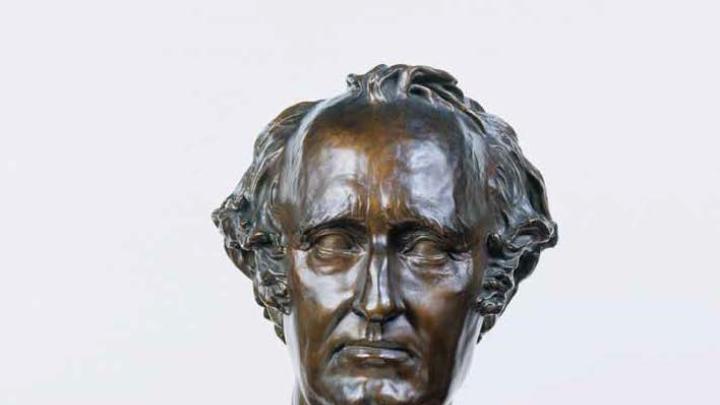

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives |

Born in his family’s home on Beacon Street, Phillips entered Harvard with the class of 1831. Social position, success in his studies, good looks, easy manners, and patrician bearing made him one of the leading men in the College; he graduated seventh in his class of 36 and then entered Harvard Law School, taking his degree in 1834. But he was never much of an attorney, despite opening a law office in Boston the next year. Spared any need to earn a living, he could afford to mark time until the real work of his life should reveal itself. He hadn’t long to wait. Two factors jolted his career out of its apparently preordained and comfortable course: meeting his future wife, and witnessing the upheavals in Boston over slavery that formed part of the prologue to the Civil War.

Phillips and Ann Terry Greene met in late 1835 and married two years later. The daughter of a prominent Boston merchant, Ann Greene is today rather a mysterious figure, but she evidently had enormous influence on her husband. A lifelong invalid who suffered from complaints both painful and obscure, she was nevertheless strong-willed, blunt, and passionately devoted to ending slavery. She had been present on October 21, 1835, when a mob estimated at 5,000 men broke up a women’s antislavery meeting, seized the abolitionist newspaper editor William Lloyd Garrison, roughed him up, tore his clothing, bound him, and paraded him through the streets. That event, and the outrage it produced in Phillips’s fiancée and her friends, began his conversion to abolition.

Boston in the 1830s was hardly opposed to slavery. Much of the city’s wealth came directly or indirectly from turning Southern cotton into cloth, and the business community favored accommodating the slave states. Massachusetts, meanwhile, regarded itself as the birthplace of the American republic and took a proprietary interest in the enduring union of the states under the Constitution. Its conservative political leaders, in particular its Olympian senator, Daniel Webster, believed that disagreement over slavery must not be allowed to weaken that union.

Radical abolitionists stood Webster’s policy on its head. With rigorous logic, Phillips insisted that if slavery was wrong and the Constitution allowed it in any part of the United States, then the Constitution was evil and therefore void: there could be no lawful union with slaveholders. “Our fate is bound up with that of the South, so that they cannot be corrupt and we sound,” Phillips declared in 1837. “Disunion is coming…for the spirit of freedom and the spirit of slavery are contending here for the mastery. They cannot live together….”

He had many opportunities to drive home the frightening and relentless consequences of this argument. After his marriage, he had begun a career on the popular lyceum circuit, which sponsored traveling lecturers. Phillips discussed historical, patriotic, and scientific subjects as well as abolition, and by the 1860s was among the best-known public speakers in the land. In contrast to the conventional long-winded, florid oratory of Webster and his like, Phillips was easy, informal, conversational, almost intimate at the podium and exhibited the unfailing good manners of the gentleman he was bred to be. Yet when he spoke on abolition, audiences found it hard to reconcile the genteel, genial speaker with the militancy and extremism of what he had to say.

Phillips’s attacks on slavery and those who would compromise with it were scathing. He called Webster “a great mass of dough” and the governor of Massachusetts “a miserable reptile.” Abraham Lincoln was “this huckster in politics” and “The Slave-Hound of Illinois.” Such talk infuriated Southern sympathizers and moderate Unionists. They hired brass bands to drown Phillips out or pelted him with eggs and bricks. More than once he had to slip out a rear entrance to elude enraged hearers, and he regularly carried a gun for self-defense. But he never ducked a hostile crowd—in fact, he seemed to thrive on them—and never softened his language.

After the Civil War, many abolitionists felt that they could rest from their labors. Not Phillips. He agitated for full citizenship for freed slaves, women’s rights, fair labor practices, temperance, penal reform, and better treatment for the American Indian. As a kind of elder statesman of radicalism, he kept up his evangel of reform, never ceasing, in his words, to strike “earnest blows on the hot iron of the present.” At his death, he received Boston’s equivalent of a state funeral: thousands viewed his coffin in Faneuil Hall. Not all the city mourned, however. One elderly Beacon Hill gentleman said that, although he did not plan to attend the funeral of Wendell Phillips, he wished it known that he approved of it.

Castle Freeman Jr. is a freelance writer based in Vermont.

A different illustration of Phillips appears in the print edition of this article [see PDF].