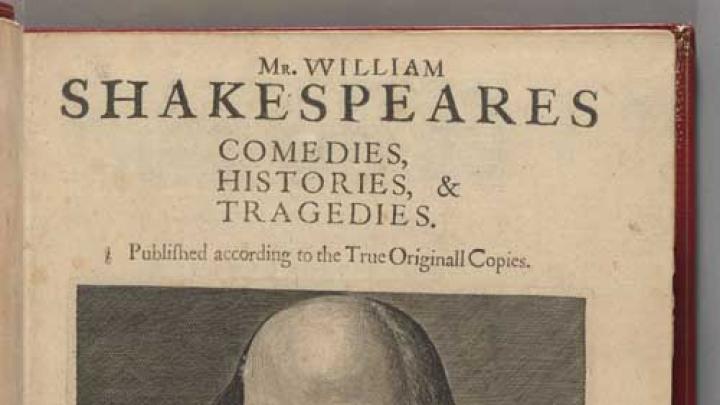

Recently, it was announced that a new copy of William Shakespeare’s First Folio, a collection of his plays published in 1623, was discovered on the Scottish isle of Bute. Fittingly, the Folio—one of just 234 known existing copies in the world—surfaced a handful of weeks before the 400th anniversary of the bard’s death, on April 23.

Though that particular manuscript will likely remain in the United Kingdom, two others can be viewed at “Shakespeare: His Collected Works,” a quartercentenary celebration at Houghton Library. Running through April 30, the exhibition includes more than 80 artifacts pertaining to the playwright’s oeuvre. It particularly focuses on Harvard’s relationship to the Bard, which may extend back in time to the childhood of John Harvard himself. His mother was from Stratford-upon-Avon, the home of Shakespeare; it’s possible that a young Harvard walked by the retired playwright.

The exhibition “reflects Harvard University’s wish to catalogue Shakespeare” for centuries, said Dale Stinchcomb, one of the exhibition’s co-curators. The copy of the First Folio owned by Harry Elkins Widener was bequeathed to the College by Widener’s mother after his death in 1912. Houghton’s other copy, from the collection of Charles Chauncy, the second president of Harvard from 1654-1671, is believed to be the first copy of the Folio to have crossed the Atlantic. The early acquisition of the Chauncy Folio is perhaps symbolic of the lengthy history of Shakespeare editorship at the University. Scholars including George Lyman Kittredge, Harry Levin, and Cogan University Professor of the humanities Stephen Greenblatt have worked on the now-standard editions of Shakespeare read in classrooms across the world, points out co-curator Peter Accardo: “Harvard has had a rich tradition in producing the texts we’ve all seen.”

Beyond the academic sphere, the exhibition displays a number of personal copies of Shakespeare’s works, marked up by their famous owners, like Herman Melville (during the same period in which he wrote Moby-Dick), Theodore Roosevelt (brought along on a safari), and John Keats (in which the poet crossed out passages of Samuel Johnson’s criticism, penning in aptly chosen lines of Shakespeare in response). The body of Shakespeare annotated by famous minds is so large, noted Stinchcomb, that a book of the playwright’s work owned by Abraham Lincoln did not make the cut for display.

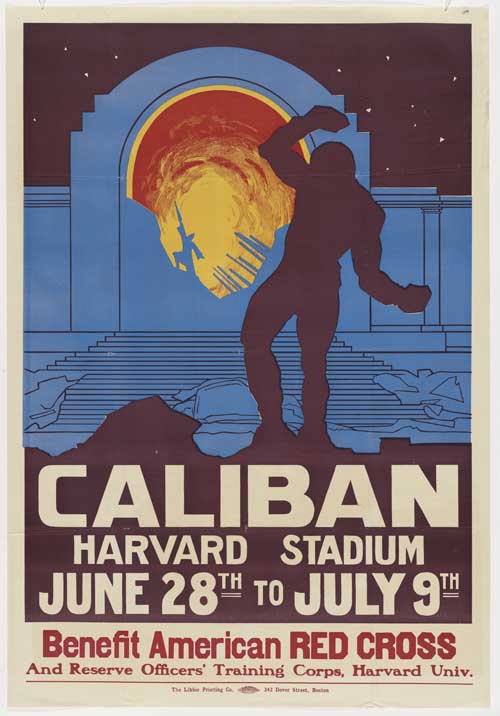

Much of the exhibit is devoted to Shakespeare’s plays as they first were enjoyed: in performance. Actors such as John Lithgow ’67, Ar.D. ’05, have taken part in campus productions and so in curating the exhibition, says Accardo, “We asked a fundamental question: When did Harvard first begin to perform Shakespeare?” The first such performance—all male and in burlesque—is believed to be an 1870 production of Antony and Cleopatra. A photograph from the production, in which one actor has thrown himself into the arms of another, is placed next to an image of a heavily made-up Lithgow as Gloucester in King Lear. As a Harvard undergraduate, Lithgow also played the title role in both Macbeth and Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II as part of a 1964 “Shakespeare-Marlowe Festival.” On one wall hangs a massive poster for a production of “Caliban,” a spin-off of The Tempest that was performed at the Harvard Stadium in 1917. As World War I tore through Europe, celebrations for the tercentenary anniversary of Shakespeare’s death were deferred to the United States. The production—one of unprecedented scale—played to thousands in order to raise money for the American Red Cross. Harvard’s graduation ceremony used to take place at the stadium, and so the Class of 1917—mostly clad in army attire, as America had recently joined the war—walked across the set of the production to receive their diplomas.

The exhibition also boasts a variety of rare photographs, like one of the two existing copies of the Booth brothers performing Julius Caesar for one night only on November 25, 1864, in Central Park, in New York City, to raise money for a statue of Shakespeare that still stands today. Ironically, John Wilkes Booth portrayed Marc Antony, who opposed Caesar’s assassination. The very next night, his brother Edwin Booth began a production of Hamlet that ran for an unprecedented 100 nights; months later, John Wilkes assassinated Lincoln at the Ford’s Theatre, in Washington, DC. It wasn’t until 1923 that the great actor John Barrymore—whose photo is juxtaposed next to that of the Booth brothers—broke Booth’s record, with 101 consecutive performances as the Danish prince.

The exhibition also addresses the history of actors of color in Shakespeare plays. On display is a lithograph of Ira Aldridge, the first black actor to portray Othello in England, and subsequently across Europe, in 1854. Paul Robeson, depicted in a poster mounted across the room from the Caliban poster, became the first black man to play Othello in America, at Cambridge’s Brattle Theater, in 1942. The handkerchief from his Desdemona, played by the legendary Uta Hagen, rests in a display case devoted to actresses of Shakespeare. A mounted photograph of Sarah Bernhardt as a skull-holding Hamlet, acclaimed for both her ingénues and breeches roles, is one of Stinchcomb’s favorite images from the collection, and it has been widely used in publicity for the exhibit.

Shakespearian productions—at Harvard and elsewhere—would not exist without the directing and stagecraft crucial to putting on a play. The exhibition draws from the Harvard Theatre Collection’s vast array of prompt books, featuring annotation from directors, actors, and designers from around the world. Stinchcomb pointed out one such book from Ian McKellen’s 1986 tour of Acting Shakespeare, a one-man show made up of anecdotes about the theater interspersed between great speeches by the Bard. The prompt book, and accompanying playbill and ticket, were likely bequeathed to the library by McKellen himself, and feature an inscription noting that, though it was an enjoyable stop on the tour, the Boston theater McKellen played in “was dirty.” The exhibition also displays striking set and costume designs from across the centuries, from those of Robert Edmond Jones, the foremost American practitioner of the “New Stagecraft,” which favored simple, symbolic unit sets over elaborate realism, to Orson Welles’s 1937 spin on Julius Caesar, which used a large red backdrop to reflect the contemporary tensions in Europe.

The age of both Harvard and its libraries, said Accardo, means that the University’s collections allows them to be “interdisciplinary in a way younger collections can’t be.” At the same time, added Stinchcomb, “it’s been a humbling experience”: the curation process pointed to objects that Houghton does not possess, such as rare editions, letters, and photographs residing in other museums and archives around the world. But as exemplified by the spread of Folios across the world—and the one just newly discovered—“No library,” he said, “can do it all.”