Streams of dining-hall workers, students, and supporters gathered in the Yard this morning as Harvard University Dining Services (HUDS) commenced a long-threatened strike. Workers have set up pickets outside undergraduate dining halls, planning to strike indefinitely until the University meets union demands to provide a minimum $35,000 income for employees who want to work full-time, year-round; and to avoid increases in workers’ health-insurance costs. The strike comes after four months of contract negotiations that had made no progress on these principal issues. “No worker who is here and ready to work should be making less than $35,000 a year,” said Michael Kramer, head negotiator for UNITE HERE Local 26, which represents HUDS workers, at a rally in the Science Center plaza this morning. “And yet, despite all of [Harvard’s] wealth, half of the workers here are making less than that, struggling to get by. And Harvard has to the audacity to ask those workers to take on more of the cost of health care.”

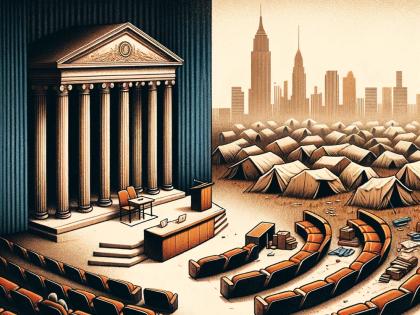

Harvard officials call the union’s demands unaffordable; the unsuccessful contract negotiations follow the University’s announcement last month that the endowment had lost more than 5 percent of its value, or nearly $2 billion, in the last fiscal year. At the same time, the union has galvanized the support of large contingents of the Harvard community by pointing to the University capital campaign’s current success, and the size of the remaining endowment (at $35.7 billion, still the largest in the world). The University points out that the average HUDS worker earns $21.89 per hour, much higher than other food-service workers, and also receives retirement benefits and health-care more generous than the industry standard. But because dining-hall workers are employed for only about seven and a half months of the year, their average income is less than $34,000. Why, the union asks, can’t Harvard use more of its resources to offer dining workers stable, year-round employment?

The union’s $35,000 income demand is still not enough to support a family in the Boston area, according to the MIT living-wage calculator, and the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Cambridge is about $3,300, more than most HUDS workers’ entire incomes. The cost of living in the already high-cost region has grown substantially during in the last decade, with the big-ticket items—housing and healthcare costs—among the highest in the country. The union’s position has resonated among many students, who interact with dining-hall staff members daily: the strike has been endorsed by both The Harvard Crimson and the Undergraduate Council, and dozens of students have shown up at HUDS rallies in the past several weeks. Harvard graduate students, who are now organizing to form their own labor union, have also been a consistent presence.

“Harvard deeply values the contributions of its dining services employees, as evidenced by the fact that they receive some of the most generous hourly wages and benefits for food service workers in the region. The fact that the average tenure of a Harvard dining hall worker is 12 years is a testament to the quality of work opportunities here,” University spokeswoman Tania deLuzuriaga said in a statement. “We have proposed creative solutions to issues presented by the union, and hoped union representatives would contribute to finding creative, workable solutions at the negotiation table. They have been unwilling to do so. Harvard’s negotiation team offered to stay though the night to continue to work on a deal, but Local 26 representatives left at 5:30 p.m. We are disappointed that they have been more interested in planning a strike than working on a solution that meets the needs of their members and the wider community,” she added, referring to yesterday’s bargaining session.

Earlier this week, in an effort to settle the contract and avert a strike, Harvard had offered summer stipends of about $150 per week for workers with between five and 20 years of service at the University, and $250 per week for workers with more than 20 years. The union rejected the offer—it represents a pittance compared to what workers have demanded.

The union also has rejected the health-insurance plan offered by Harvard, which is identical to the plan the University negotiated with the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers (HUCTW) earlier this year. (Members of that union earn significantly more than HUDS workers, with most making more than $55,000). The plan would create a new health-care tier for employees earning less than $55,000, who would pay the least in monthly premiums. Under the current health-care plan, the lowest tier includes all workers earning less than $70,000, who contribute 15 percent of the cost of their premiums. The sub-$55,000 tier would contribute 13 percent. That would make next year’s premiums for workers in that tier, which represents the majority of HUDS workers, lower than they are this year, despite annual increases in insurance premiums. But Local 26 rejects the plan because of its increases in co-insurance: emergency-room visit copayments would increase from $40 to $100, and hospital inpatient and outpatient services from no copay to $100. Doctor’s office visits would also increase slightly, from $15 to $20 next year and to $25 in 2018. To offset these out-of-pocket costs, the University also offers a reimbursement plan that kicks in after a worker has spent $480 on such expenses under an individual health plan or $890 for a family. (See here for a report on the University’s 2017 insurance plans for non-unionized faculty and staff.)

This week, the University offered small modifications to that plan, adding to it modest funding for a flexible savings account of $80 per year in 2018 and 2019, and $40 in 2020. The union has again rejected the plan but hasn’t proposed one of its own. Alternatively, the University has also offered to pay the equivalent cost of its health plans for dining-hall workers who wish to join Local 26’s health plan. Currently, about 300 of the union’s 750 members choose that plan.

The Racial Justice Coalition, a student group at Harvard Medical School, recently released an analysis arguing that Harvard’s proposed health plan is unaffordable under Massachusetts guidelines and significantly more expensive that what HUDS workers would receive on the state insurance exchange. The report shows that a family of three earning $30,000 per year would qualify for a state insurance plan with no premium and no copayments; under Harvard’s plan, the monthly premium would be over $200. But a worker can only qualify for state subsidies if her employer’s health-plan premium for an individual exceeds 9.5 percent of her income; family plans are excluded, and thus most HUDS workers would not qualify for a state-subsidized plan.

Sanjay Kishore, a second-year medical student and a member of the Racial Justice Coalition, stressed that access to affordable medical care is central to the group’s mission. He added, “We believe Harvard should provide access to health care that’s on par or better than what the state of Massachusetts would provide to low-income workers.”

As of this morning, dining halls are being operated by managers, who are not represented by Local 26, and three House dining halls have been closed.