Edward Gorey ’50 might have hated Gorey: The Secret Lives of Edward Gorey, a new dramaturgical take on the writer-illustrator’s life. Not because the play is bad — to the contrary, playwright and director Travis Russ has crafted a story with the same shifting texture, poignant darknesses, and unexpected delights as one of Gorey’s own works. But to the extent that an audience member might leave the theater feeling acquainted with Edward Gorey, the historical, human figure, he may well have considered that an insult. Knowability was anathema to him.

Toward the beginning of Russ’s play, a recording of one of Gorey’s final interviews resounds throughout the theater. “Is there anything people don’t understand about you?” the interviewer asks. “Yes…no,” Gorey responds. He gives an equally ambivalent answer to the follow-up—is there anything he would like to help people understand? Gorey answers, simply, that he would like to be read.

And he is: Gorey’s spindly, peculiar creatures have populated countless childhoods, including mine. But Gorey himself kept carefully out of view throughout his life. He famously wrote under more than 200 pseudonyms, typically gothic anagrams of his given name, like Ogdred Weary and Raddory Gewe—“Why be one person when you could be hundreds?” the play’s Gorey character cheekily asks.

In Russ’s play, three versions of Gorey—one college-aged (played by Phil Gillen ’13); one a young adult; and the other an old man —bound about the stage, pulling artifacts from towering, overstuffed shelves and lovingly spinning out the personal history each contains. Gorey was famously a recluse, especially later in life. Though his books are often categorized as children’s books, Gorey neither had nor particular liked children. He had no publicly acknowledged romantic relationships, and only a smattering of rumored ones —with men, though when confronted about his sexuality, he consistently demurred. As a young man at Harvard and in New York City, he shrouded himself in full-length fur coats and dazzled with fingers full of rings; he cultivated eccentricity, alternately claiming to hate interviews and using them to spin out new fabrications and embellishments on the story of his life. Later, he retreated more literally, holing away in a rickety house in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts. He took in boarders in the form of stray cats and a family of raccoons, but rarely saw people. Instead, he surrounded himself with objects, ranging from the functional to the inexplicable: 22,000 books, 93 VHS tapes of The Golden Girls, 73 door knobs, a box of antique post-mortem photographs of babies.

It was among these accumulations (Gorey called them collections), on display in his house-turned-museum in Yarmouth Port, that Russ initially got the idea for the play, about seven years after Gorey’s death in 2000. The tour, Russ remembers, was barely 20 minutes long. Despite the abundance of objects Gorey left behind, interpreting their significance is nearly impossible. Combing through the museum’s materials, compilations of Gorey’s correspondence, and the few archival records of his early life, Russ struggled to compose a coherent portrait of a man who apparently wanted nothing more than to remain an enigma. Ultimately, quotations and imagined monologue, fiction and fact (and Gorey’s statements, which were often somewhere in between), are all woven together into a fast-paced, chimerical text.

The resulting play, Russ admits, could be demeaned as “academic.” It is explicit about its hypertextual references, and in its difficulty determining a true narrative of Gorey’s life, it lays bare some of theater’s inherent falsifications. A linear story with a typical, satisfying arc of conflict and resolution, Gorey certainly is not. But, Russ argues, such a structure could never capture the singular character of Gorey, who lived so many of his own stories at once. The fourth wall is gleefully, repeatedly shattered, and the characters speak to one another across time, each chiming in on the others’ stories to corroborate or correct the narrative. As the play goes on, the three Goreys come to seem more and more like a family. Their happy rehearsal of history— affectionately retreading the familiar stories, tweaking and squabbling here and there—recalls nothing so much as married people building their shared mythology, a safe world all their own.

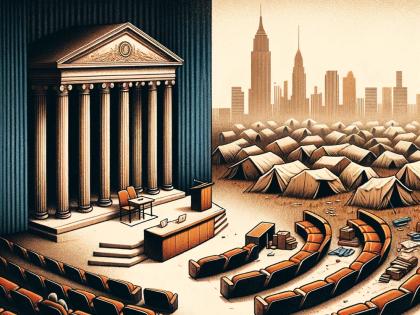

Russ recalls learning that the real-life Gorey kept his friends separate from one another—so friends discovered their mutual friendship only when they encountered one another at his funeral. It’s tempting to read all the smoke and mirrors as a kind of shield against internal pain or fear of the outside world. To some extent, Russ indulges that instinct, fashioning narrative resolution from a sparse historical record. Gorey’s rumored infatuations, in the play, become fact: first with Harvard roommate Frank O’Hara, then, most notoriously, with New York City Ballet choreographer George Balanchine. Gorey did attend every show that Balanchine choreographed at the New York City Ballet, and had the autographed programs to prove it. In the play, he rhapsodizes about “genius that makes times stop.”

Soon after, the middle Gorey delights in Christmastime rituals of solitude: people-watching from the window of a New York City diner and marathons of silver-screen ingenues. But when Balanchine leaves the city, Gorey becomes dissatisfied with the elaborate self-sufficiency he’s fashioned for himself and heads to Yarmouth, hinting at a loneliness he’d rather not confront. “Did something happen to me? When was it?” the youngest Gorey demands, quaking, as he comes to realize what his future holds. The older Goreys don’t answer, except to sigh, “Oh, kiddo,” and lay on sympathetic hands. A theatrical audience may eagerly fill the silence with its own extrapolations.

The truth, such as it exists, might be more complicated. Rather than lonely, Gorey often claimed to be basically disinterested in romantic partnership, even attributing some of the childish appeal of his books to asexuality. “I never said I was gay, but I never said I wasn’t,” the real-life Gorey said. At its best, the play welcomes this and other contradictions, allowing them to share the spotlight Gorey seemed both to shy away from and to crave. On the stage, as in life, he remains resolutely unresolved. He was, the play’s Goreys harmonize, in “a category of one.”