The museum gallery is a space designed to be in permanent flux. In 2008, artist Michael Asher sat down with 10 years of exhibition blueprints from the Santa Monica Museum of Art, reviewing the designs of 44 shows that had gone up in the main gallery. He then reinstalled the underlying armature of each and every temporary wall, now only metal skeletons stripped of the drywall that formerly gave them substance. All past configurations were present simultaneously, filling the room with a dense metallic labyrinth. The original walls had been built to disappear into the background, in order to highlight the art they displayed; Asher’s reconstructions exposed the transience of that art, and the off-putting flexibility of the space it inhabited. Looking at images of the work feels like catching a glimpse of something the institution wants to hide: the bones of the gallery itself.

A similar sensation comes up in conversation with Justin Lee, an architect based in Somerville, Massachusetts,* who designs exhibitions for the Harvard Art Museums. He knows the new museum better than anyone, having designed the building as project architect while affiliated with the Renzo Piano Building Workshop, which Harvard hired to renovate the museums. Lee earned a master’s in architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 2004, so when the workshop took on the project, he was the natural pick for the job. (As a student, Lee lived on the corner of Prescott Street and Broadway, mere feet away. Each morning and evening, he strolled past the museums’ previous incarnation, unaware that he would effect a drastic change in the landscape of his design education.)

To Lee, the museums’ activities fall roughly into two categories. First, there’s the internal: the business of collecting items, and then researching, storing, and preserving them. Then there’s the more visible task of making these works available for visitors to experience. Harvard Art Museums’ attachment to a university further complicates matters: the museum caters first to the needs of students, classes, and instructors, and second to those of the general public. The space was specially designed to facilitate each of these functions without inhibiting any of the others, he explains. The building channels different groups—staff, students, and the public—along distinct routes, designed so each type of museum-goer becomes invisible to the others. You see only what you are supposed to see.

He points out the elevators as an example: if you visit frequently, he says, you’ll notice that one set of doors never opens. Though it looks like the other two, this particular lift is for staff moving art between the research centers on the upper floors and the compact high-density storage below ground. The button visitors press will never call it. On days when one of the other two public lifts is out of service, a flip of a switch makes that special third lift available to museum-goers, none the wiser that they’ve been given special access to something normally off-limits. Lee’s work requires him to deeply consider how people move through buildings—or rather, how buildings move people. His explanation is reminiscent of the body’s circulatory and lymphatic systems: two entirely separate circuits of sealed-off channels carrying distinct substances through a single body. Good architecture makes navigating a space fluid and unconscious.

Since the renovated museums complex opened its doors, Lee (who started his own studio, Justin Lee Architecture + Design, in 2015) has designed their exhibitions.* He’s responsible for translating vast curatorial dreams and concepts and narratives into concrete physical space. Exhibition designers are always playing catch-up, he says. By the time he arrives on the scene, the curator has already been researching and conceptualizing an exhibition for months, if not years. Usually there are far more pieces that fit well with an exhibition’s theme than can actually fit into the space. Every piece has a different story to offer, a whispered message which, together with all of the other works, crescendos into the overarching narrative of the show. It’s the curator’s job to decide which message to send; Lee’s is to make sure each little voice is heard.

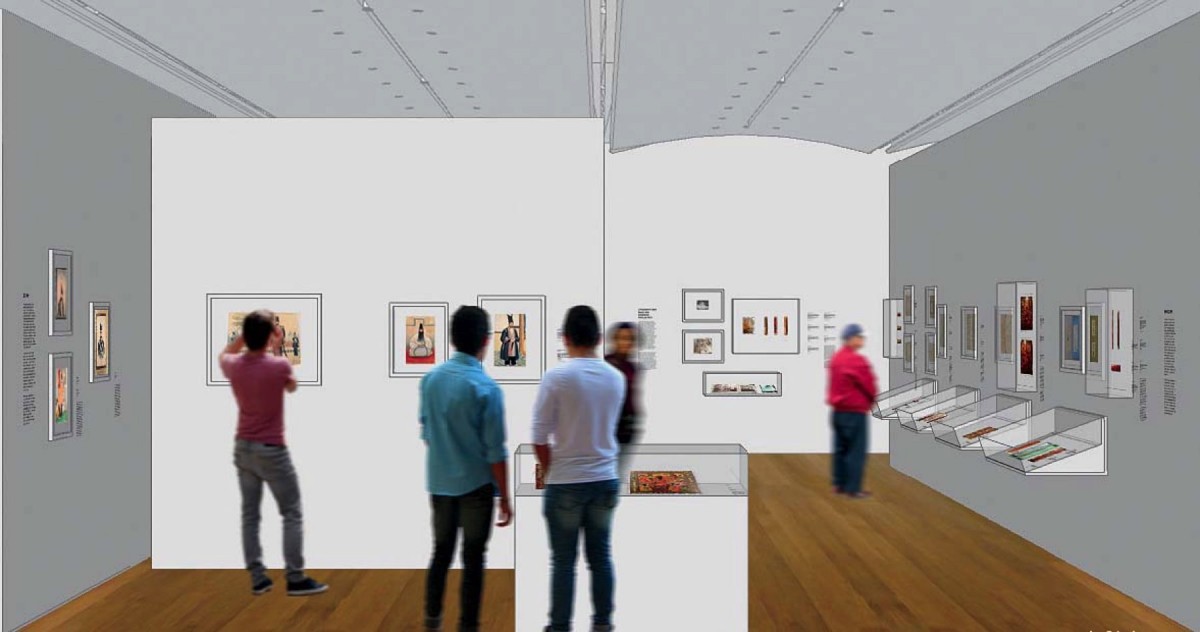

Sketches © Justin Lee Architecture + Design

When he’s designed an exhibition well, he says, no one can tell he’s done anything at all. When he’s visited spaces by designers who flaunt their personal style, his experience of the art got lost beneath thinking about the layout. This isn’t his way. If his gallery space does its job right, it enables visitors to get lost in the artwork, oblivious to the room around them, and then to find their way out again.

Lee has worked on diverse exhibitions, including “Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia,” which ended this past September, and “Inventur,” a show on 1940s and ’50s German art that will open in February. On view in May is “The Philosophy Chamber: Art and Science in Harvard’s Teaching Cabinet, 1766-1820” (see “The Lost Museum,” page 42), featuring some of the earliest items Harvard collected. In the beginning, the museum was a single large room. Well-to-do patrons and ordinary citizens who traveled the world would return with mysterious trinkets and artifacts and add them to the College’s holdings. Rarely did these early collectors know anything about the items on display; objects were categorized merely by their date of arrival. Knowledge of the world, as embedded in these artifacts, was not yet differentiated. As the collection grew, its caretakers learned more about its contents and about how to classify and categorize them accordingly; the campus grew and divided in tandem with its museum. Various buildings sprang up to house the newly distinct departments, and the museum’s contents were scattered across campus. In the exhibition, Lee is interested in breaking down these barriers to allow these objects to once again inhabit the same space, centuries later.

Indeed, permeability is a major ethos of the post-renovation museums. Passersby should be able to tell clearly from any vantage point what the building contains, and be able to enter from both sides. The individual rooms of the galleries should melt into one another, facilitating a seamless viewing experience. Daylight is crucial: Lee doesn’t want a labyrinth of sealed, artificially lit ice cubes. For him, blocked daylight provokes suffocating claustrophobia that disorients visitors and detracts from the art.

The building has its own set of rhythms. Visitors float in and out; Lee’s exhibitions materialize and dematerialize on seasonal cycles. The museum itself gets renovated and eventually will be renovated again. The institution is designed to accomplish the paradoxical task of harnessing transience to ensure permanence: it has to make the slice of the past with which it has been entrusted both secure and accessible. Lee makes it look effortless.