Dean norris ’85 is headed home by limousine after finishing a photo shoot with—he kids—“a few underlings from the network”: CBS Entertainment president Nina Tassler and CBS Television Studios president David Stapf. The 50-year-old actor seems to be taking the media attention he’s receiving in stride.

“Under the Dome turned out to be a huge summer success,” he explains matter-of-factly. “And it was profitable from day one, so it was a big game changer from a business standpoint.” A rare summer triumph for network television, CBS’s Dome, based on a Stephen King science-fiction novel, was anchored by Norris as “Big Jim” Rennie, a power-hungry local politician in a town suddenly cut off from the world by an invisible barrier. Season two will begin production in March.

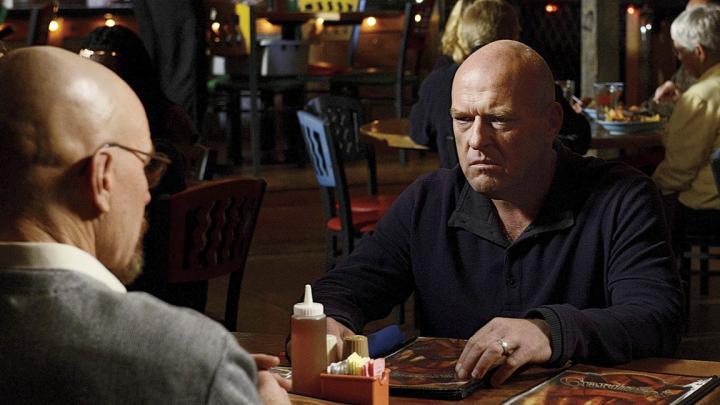

But Norris is perhaps best known for playing Drug Enforcement Administration agent Hank Schrader on AMC’s cable series Breaking Bad, which won 10 Emmy Awards during its seven-year run, including Outstanding Drama Series in 2013.

In an industry often criticized for emphasizing youth and good looks over talent, Norris’s leap to leading man in middle age sounds improbable. Yet his stardom is well earned, especially considering his many credits for performing smaller film and television roles as a character actor in the past quarter-century, in shows from The Equalizer and NYPD Blue to CSI and The Mentalist. “I was slotted into [parts playing] cops and military and CIA,” he recalls. “There was always plenty of that out there, so I was able to make a good living just going from show to show and movie to movie.”

Norris grew up in South Bend, Indiana. “It was the Rust Belt,” he says. His grandparents were Hungarian and Polish immigrants who worked in the factories that fed Detroit auto plants and, luckily, retired before the oil embargo of the early 1970s changed the industrial landscape. His father, who owned a furniture store, played in a band on weekends, like many of his other relatives. By the age of nine, Dean was sitting in on guitar and getting a taste for performing. “When I got older,” he remembers, “I realized I wasn’t good enough as a musician to make any money.”

His first performance was in Richard III; at age five, he played a young prince in a Notre Dame University production. There were other roles at the university and as a high-school student, but Norris says it was his Harvard experience that truly prepared him for the career that lay ahead. “I remember one day when I literally had three plays in my head at the same time,” he recalls. Typically the social-studies concentrator acted in five or six plays a year: on the Loeb main stage, in the Loeb Ex’s black-box theater, and in House productions. The professional American Repertory Theater was freshly arrived in Cambridge from Yale, so he also got the chance to understudy or take on small roles there—superb training for the demands he later faced.

“You have to be able to get into different characters quickly,” Norris says of his job. “Because if you’re guest-starring on a show, you get one or two takes and that’s it. And for me, so much of that came from doing theater, where you don’t have takes.”

After attending the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, Norris moved to Los Angeles in 1988. “I always knew that I’d be a middle-aged actor,” he says. “Even at 25, I was playing 35. It wasn’t until 35 or 40 that I grew into my age.”

But television has evolved to his benefit. Norris credits NYPD Blue and actor Dennis Franz in particular for bringing more grit and intensity—not to mention better acting—to the small screen. The show welcomed actors he calls “real-looking people.” And today’s cable shows have further exploded the strictures once imposed by the networks because, as Norris says, “all of this talent moved [to cable television] from independent movies, which are very difficult to make any more.” Norris likens film to the short story and serialized cable to the American novel. “With Breaking Bad, for example, it’s like you have 62 chapters that tell this long and complicated story—and to then think I’m going to do a movie? It’s like a moment in time.”

As for being a “character actor” in the future, Norris asserts, “I think if you act, you act,” adding, “Those lines have blurred. That’s a term left over from when you had good-looking Hollywood guys and everybody else.”