Our Towns

I was pleasantly surprised to see that one place the Fallowses covered was my hometown and current place of residence, Sioux Falls (“Our Towns,” by Lincoln Caplan, May-June, page 44). After 17 years as a pastor in a Wisconsin suburb of the Twin Cities, I was also amazed to return here to find that, indeed, the place I’d grown up in, surrounded by descendants of immigrants from Scandinavia and other parts of northern Europe, was populated by tens of thousands of people from Ukraine, South and Southeast Asia, Lebanon, Syria, Liberia, Nepal, and Latin America, and that dozens of languages have enlivened the streets and dining scene. From my pastoral perspective of seeing a very diverse world now represented all around us here in the Heartland, perhaps the article could have been titled, “What the Heaven is Happening in America?”

While I no longer hear the Swedish my immigrant grandparents spoke, I do hear what may well be Swahili. Mirabile dictu!

Rev. Randy Fredrikson, M.Div. ’72

Sioux Falls, S.D.

Then and Now

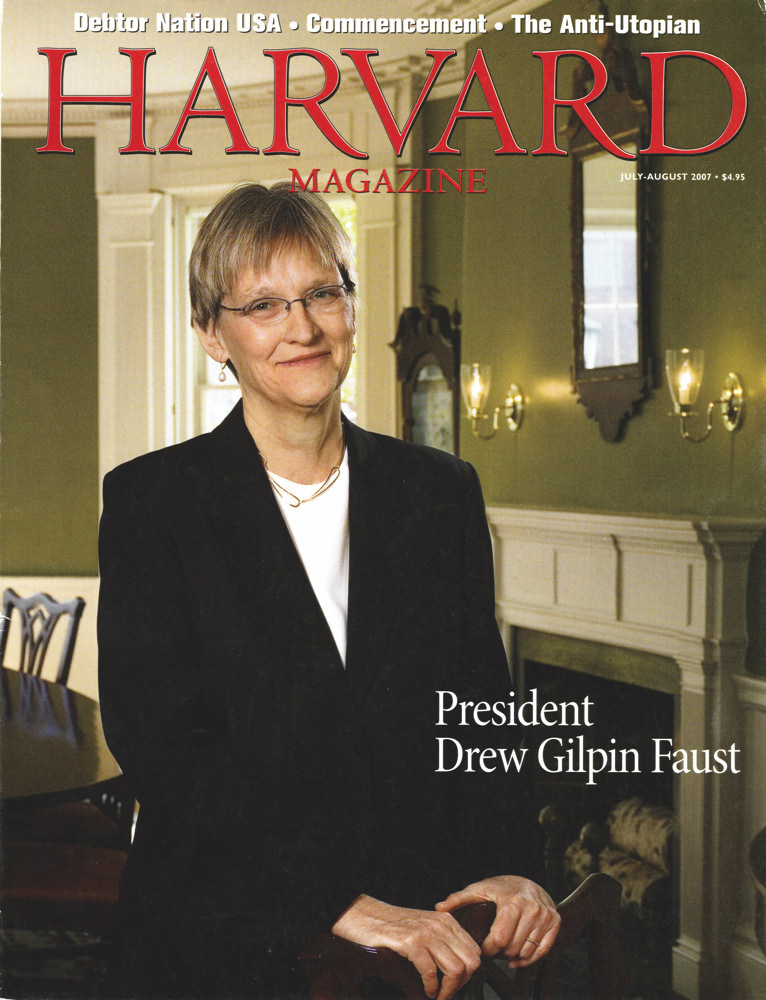

On this issue’s cover (above), Drew Gilpin Faust at Massachusetts Hall, May 9, 2018, and left, as Radcliffe Institute dean and president-elect, April 26, 2007, at Fay House (July-August 2007 issue). Her Commencement address, and valedictory, appears here. An overview of her presidency begins here.

Reading the recent article about puddle-jumping across the country in a private plane, trekking from one big-small-town to another, to get a journalistic sense of what the heck is happening out there, both fascinated and disturbed me. Romance and nostalgia reminiscent of Lindbergh, to be sure. Likely a trifle pricey, though bold and unique in conception.

But the need to criticize Trump administration policies that somehow run counter to what is “in the country’s best interests” confused me. Precisely which policies? The repatriation of trillions of dollars in business profits parked uselessly overseas awaiting reintroduction into our economy by way of tax reform…which we now have? Or the completion of the Keystone pipeline which we hope will avert catastrophic railcar disasters like what occurred in Quebec and Virginia? Is it the aggressive and successful stance taken against rogue militarism in North Korea, Syria, and now Iran? The willingness to protect our southern border with an effective wall and a network of judges doing the business of the people who placed them on the bench in the first place? It must be the positive attitude of our president about the dignity of work and his belief in perpetuating a durable middle class that is supported by rethinking our long out-of-balance pay scales. Surely that must rankle the privileged, the overpaid, overeducated, and the underworked everywhere.

What mental myopia is it that still invests the “best and the brightest”? I know not, but vow to be in-the-face of that self-serving myopia wherever I can. Elitism needs to come to an end, soon, or else colleges themselves may cease to be relevant.

Thomas M. Zubaty ’72

Marstons Mills, Mass.

Lincoln Caplan’s article on the flights of the Fallowses made me angry at first, then just sort of resigned. Your audience of educated Americans does not cotton to anger or any sort of negativity; it’s off-putting, but I fear premature optimism can derail reform. My take-away from this article is that “everything’s going to be OK here in the USA”—that there are many examples across the land of Americans doing excellent things to make America a better place.

I enjoyed reading the Fallowses’ diverse array of examples but…where I have lived during the past five years (Lebanon, Tennessee, countryside and Hoquiam-Aberdeen, Washington), I see an incredible number of troubled, damaged, poisoned people—primarily at Walmart, which is the halfway point on my evening walk. The Walmart customer base in both Middle Tennessee and on the Washington coast tends to be grossly overweight, and far too many are morbidly obese. It is sad to see so many overweight young children and teens in my community. Obesity is a recent problem due to the to the toxicity of much of our “food.” Americans have been and continue to be poisoned by our food suppliers and drugged into oblivion by Big Pharma. I see many victims of drug abuse on the streets of my community.

As Americans try to rebuild, after the middle-class gutting of the past 30 years, they are battling (being cannibalized by) our own large corporations. This makes me intensely angry. I call this Cannibal Capitalism. I would like to see a writer for Harvard Magazine investigate this vast, horrible problem to any degree, i.e. try to answer the questions, “Why are so many Americans obese?” “Why are so many Americans addicted to drugs?” You would, of course, soon find yourself at odds with several big corporations whose profits expand the endowments of our Ivy League hedge funds, er…I mean universities. Do you have the courage to take on these corporate monsters who are poisoning not just Americans but the citizens of the entire globe? It is Harvard’s responsibility to help fix this towering problem.

Jim Blake, M.Arch. ’79

Hoquiam, Wash.

Two gems struck me in the May-June issue: Eunice Shriver’s founding of the Special Olympics (Vita, by Eileen McNamara, page 42), and Deborah Fallows’s dedication to family over career.

Shriver employed her advantages in life to dignify the disadvantaged. Fallows lived the vital truth that “parents are the most important factor in their children’s lives.”

Thank you for recounting their inspiring actions and words.

Martin Wishnatsky ’66, Ph.D. ’75

Prattville, Ala.

Thank you for “Our Towns” May-June, the Fallows exploration of “what the hell is happening in America.” I lived the first 30-plus years of my life in rural, small-town America. In 2016, a mini-version of the Fallowses’ trip put me in one of Wisconsin’s poorer counties, where I grew up. I too felt a sense of renewal, despite all odds. Yes, our [article says “their”] “country is a big, open vessel of possibilities that divergent places are realizing wonderfully in their own ways, despite much better known troubles.” But we still need some shared visions for our country—all of it.

I’m one who senses a “deeper rot.” Not only is national politics and governance “genuinely troubled” as noted, but our most widely shared national belief may be: “For the United States as a whole, the very idea of ambitious ‘national greatness’ projects seems preposterous.” The interstate highway system, let alone the Marshall Plan, feels as ancient as Roman aqueducts. Is rural broadband in the model of the New Deal’s R[ural]E[lectrification]A[dministration] too big a stretch in the twenty-first century?

Our country’s founders, unaided by social media and cable TV, gave geo-graphy political potency beyond populations of voters, e.g. the Senate, the Electoral College, and requirements for Constitutional amendments. They imagined, as we should now, politics gravitating out of shared values, respect and compromise—practical behaviors rooted in empathy, if not sympathy. As Trump embarks on Smoot Hawley 2.0, we see a government no longer capable of navigating issues as complex as trade relationships essential to US agriculture—and the equipment, logistics, and supply-chain jobs it supports—while advancing U.S. interests in other industries and defending intellectual property.

Echoing 1980s James Fallows: the U.S. ought not “try to be more like Japan but instead to be ‘more like us’…,” the article concludes that America needs to be “more like itself again.” No “instead” country is named. I’ll name one Fallows knows well: China.

Do we envy China’s migration of rural people to urban centers; or poisoning its air and water? In our big beautiful country, is it still useful to build sprawling concentric circles of suburbs with soul-sucking commutes to city centers devoted to financial services, media, and advertising? Urban and even suburban space is too expensive to actually make “tangible things” there.

Does it bother anyone else that Silicon Valley, epicenter of the everywhere-connectedness Gospel, is a place of campuses and company towns? No one I know at Google has ever met each other. Years ago I watched engineers in three different time zones design a part for manufacture using shared software in the course of a TED Talk. Anything complex is assembled from parts made all over the world; political messaging for American social media is made in St. Petersburg, Russia. Might we be better off with universal broadband and infrastructure to get around our country more efficiently?

With the financial industry dominating the real economy more than ever, advertising now devolved to surveillance capitalism, and connectivity mostly a corporate content-delivery system that distorts and distracts from actual human connections, don’t we all need to own the cultural, economic challenges facing our country—all of it?

Despite 20-plus years in the Harvard Club of New York City and political affinity for causes called progressive, like equal rights and universal healthcare—drivers of economic productivity and competitiveness if done right IMHO—I sense part of the “deeper rot” is coastal urban hubris that’s gone beyond a mere foil for divisive right-wing politics to the point of enablement.

In 1989 my late wife, a college recruiter, relayed a story told by a recruiter for Vassar about interviewing a high-school senior in Nebraska. The 17-year-old girl articulated more thoughtful insights from taking her steer to the Nebraska State Fair than the recruiter heard from privileged high-school girls’ tours of the Louvre. Nowadays privileged kids’ parents hire “advisers” to assure their children write better essays and give better interviews. In the meantime, the places Fallows calls “our towns’ provide a disproportionate number of men and women in military service to fight our wars, as do communities of often disadvantaged racial minorities. The only good to come from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are young veterans now running for office.

The Marshall Plan reminds me that Americans thought big and different long before Apple’s ad agency told us to think different. We need to get back to that—together.

John A. Skolas, M.B.A. ’88

New Hope, Pa.

Speak Up, Please

Harvard Magazine welcomes letters on its contents. Please write to “Letters,” Harvard Magazine, 7 Ware Street, Cambridge 02138, or send comments by email to yourturn@harvard.edu.

Tax Reform

In his article, “Tax Reform, Round One” (Forum, May-June, page 57), Mihir Desai states: “A major rationale for the corporate reforms is to incentivize corporate investment, prompting…ultimately, greater wages for workers.” The article also notes that that “[t]he most significant individual-tax changes…largely accrue to high-income individuals.”

However, what incentivizes businesses to invest is a perception of greater demand for their goods and services. Lacking that perception, a business will not invest to expand its operations no matter how much additional cash flow tax reform provides. It would be folly to do so. And if the business perceives a greater demand, it will generate or find the funding to expand without the need for a government subsidy.

Further, the given in economics is that consumption—the demand for goods and services—is the most powerful of economic forces. Consumption is what makes economies go ’round. Even economies that rely on exporting their products depend on the demand for those products elsewhere.

Surely, then, moderating the corporate and individual tax changes to favor the lower- and middle-income earners would directly and immediately lodge more cash to spend in those people who most support our economy by their consumption of goods and services. It’s called trickle up economics.

Peter Siviglia, J.D. ’65

Irvington, N.Y.

What would “Tax Reform—Round Two” look like? Round Two exists!—It’s been long buried in Congress, the bipartisan 2017 Fair Tax Act (HR25, S18). The act was first introduced in 1999, thoroughly researched and developed by some 80 leading economists, including a Nobel laureate.

It’s the best tax plan ever, but Congress won’t mention it. Why? Because it abolishes the IRS, and members of both parties would lose their power and money-selling tax favors.

The proposed legislation rids businesses and individuals of the income tax, replacing it with a retail sales tax. Instead of raising government revenue by taxing the relatively few who have income, the Fair Tax Act taxes everyone in the U.S., not only citizens but all who buy services or new goods. For the first time, undocumented aliens and criminals pay taxes, plus the hordes of tourists visiting the U.S. No one avoids paying taxes!

To make the tax truly fair, all citizens receive a monthly sum based on family size—their yearly total depending on the government’s definition of poverty.

With the Fair Tax the government’s revenue may exceed what the income tax now brings in. Prices may drop significantly as the huge, unacknowledged costs of the income-tax system evaporate: businesses and individuals will no longer waste time confirming earnings and justifying deductions; tax-avoidance experts won’t need to be paid; non-productive tax record-keeping will be eliminated; and businesses that collect tax revenue will file a vastly simplified, one-page monthly form.

All will love the Fair Tax—except congressional leaders losing their power!

Richard G. Rettig ’51

Oceanside, Calif.

Mihir Desai’s article on the tax law presented a very enlightening outline of its multitudinous features. I cannot, however, agree that the provision for expensing of new investment in equipment ensures “no distortion to investment decisions.” This provision gives preferential treatment to equipment investment not in line with economic reality, biases decisions among categories of investment, and distorts decisions on investing versus leasing of equipment.

Robert Raynsford, Ph.D. ’66

Washington, D.C.

The article on the tax bill only touched lightly on hidden taxes. When deficit spending raises prices, goods and services are taken from the public, the same thing as taxes. If one is given a tax cut of 5 percent and the price level goes up 12 percent, the tax level actually went up 7 percent. Keynes pointed out that government can live a long time on “note printing,” but the longer it lasts, the worse the eventual outcome.

Edmund R. Helffrich ’49

Allentown, Pa.

Mihir A. Desai’s “Tax Reform, Round One” is a splendid explanation of the new tax law. But he might well have given some thought to whether two of its limitations do violence to the Sixteenth Amendment, from which it purportedly draws its warrant. Here are my thoughts on this constitutional issue.

The new Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) dramatically reduces the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent and also slightly reduces individual rates. It doubles the standard deduction. But it also questionably purports to limit the business interest deduction and fully to bar deduction of “expenses for the production of income,” including fees paid for investment advice.

In doing so Congress ignores the Sixteenth Amendment, in effect treating it as a nullity. The Sixteenth, we recall, was designed to overrule Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., in which the Supreme Court held the income tax a “direct” tax and thus constrained by the apportionment clause. That is, as a “direct” tax it must be allocated among the states in relation to their respective populations. The Sixteenth does this by creating an exception to the apportionment clause for “taxes on income.” All other “direct” taxes remain subject to apportionment.

That brings us to the question as to whether the unapportioned tax laid by the TCJA is any longer a tax on “income” because it disallows or limits deductions that in 1913 (when the Sixteenth was adopted) were universally considered deductions necessary to arrive at “income.” Today no accountant or economist would argue with that settled meaning. If such settled deductions be disallowed, to that extent the tax is no longer on “income” but on gross receipts.

It is unlikely that the Supreme Court would hold the entire Internal Revenue Code unconstitutional. More likely if this issue were presented it would “patch up” the TCJA by holding the limitation on business interest and disallowance of “expenses for the production of income” (including fees paid for investment advice) void. Taxpayers should thus continue to claim these wrongfully barred deductions and be prepared to litigate if challenged.

W.D. Thies, J.D. ’59

New York City

Author’s Query

Historian Jonathan Daly (uic.academia.edu/JonathanDaly) is writing a biography of the late Russia scholar Richard Pipes, Baird professor of history emeritus, who taught at Harvard from 1958 to 1996. Daly would be grateful to hear from anyone who studied, particularly as an undergraduate, with Professor Pipes and is willing to share thoughts and reminiscences about that experience. Contact him at daly@uic.edu or at UIC History, University of Illinois at Chicago, 601 S. Morgan Street, M/C 198, 913 University Hall, Chicago, IL 60607.

Truancy: A Research Agenda

In “The Power of a Postcard: Trimming Truancy” (May-June, page 8), Harvard Magazine touts the research of Todd Rogers, in which using postcards mailed to students’ homes to inform parents of their children’s absences from school was successful in reducing student absenteeism. The article goes on to say, “Schools are paying attention [to this research]. The federal government’s new education law, the Every Student Succeeds Act, has led at least 36 states to select student absenteeism as one of the metrics on which their educational quality is evaluated.”

I applaud Rogers for his work, but I wish we knew the outcome of the reduction in student absenteeism. Do these reformed “truants” become more engaged in the educational process when their absenteeism decreases, thus improving their academic performance, or do these students, who perhaps never wanted to be in the classroom in the first place, become classroom disrupters who prevent other students from learning and thus reduce everyone’s academic performance?

Using absenteeism as a metric is measuring a process; it is not measuring an outcome.

Michelle Hutchinson, D.M.D.-M.P.H. ’87

Marietta, Ga.

Editor’s note: In reporting on the research, we were not expressing an opinion on it. The research continues, and, as Michelle Hutchinson notes, now that Todd Rogers has discovered an effect, it will be interesting to determine its wider influence on schooling outcomes—particularly for those students who attend classes and might not have otherwise.

Shopping Week

It is regrettable that the Harvard faculty is once again talking about eliminating the “shopping period” during which students can try out a number of classes at the beginning of the semester before making a final selection (“Toward Preregistration?” May-June, page 27). The faculty tried to eliminate it in 2003, and fortunately they did not succeed then. The extraordinary value of the shopping period should not be weighed against small inconveniences for the faculty, such as those described in the recent article in Harvard Magazine. The suggestion that students could get the same information from video clips during a pre-registration period as they get from sitting in a classroom during shopping period is misguided and shows a lack of appreciation for the importance of live interactions.

The shopping period is a unique Harvard activity with creative educational benefits. It encourages students to try new areas of Harvard’s wide offerings. This is true for students of all backgrounds, because most students arrive at Harvard with pre-conceived ideas about what they want to study, and they come from secondary schools where courses can be chosen only within certain limits.

In my own case, I arrived at Harvard as a freshman in 1965 planning to take government courses because I had spent the previous summer working at the U.S. Senate. The shopping period encouraged me to explore the richness of Harvard’s course offerings, and I ended up taking an anthropology course, a philosophy course, and a psychology course, as well as auditing a second philosophy course, during my freshman fall semester.

Edward Tabor ’69

Bethesda, Md.

Enabling Expertise

The letters of Don Kingsley and, to a lesser extent, Howard Landis, appearing in the May-June issue (pages 4 and 6, commenting on “The Mirage of Knowledge,” March-April, page 32), betray a fundamental unawareness of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. They both recite how alleged “experts” screwed up presumably better systems that existed before the experts got their hands on them.

But that’s not how the universe works. We are constantly battling the tendency toward disorganization, and there is no evidence whatsoever that the efforts of our experts prior to the “horribles” of the last 30 years fared any better. Failure should not lead to abandonment of whatever expertise seemed most appropriate at the time, but to a renewed and stronger effort to increase the information that will underlie whatever expertise we will appeal to in the future.

More and wider education is the only answer, especially of women!

Bruce A. McAllister, J.D. ’64

Palm Beach, Fla.

Donald Trump and the movements that contributed to his political success are not solely to blame for the distrust, disdain, and cynicism about “experts.” More plausible reasons are: 1) experts who step beyond their boundaries for ignoble motives; 2) corruption among experts (who are as human as anyone else); 3) the mistaken conflation of credentialism with expertise; and 4) the hyperbolically superlative adulation for fraudulent celebrity experts—some famous recent examples including (Harvard-educated) Albert Gore and Barack Obama—which would be comical if their influence weren’t so destructive. Just because Donald Trump can be crude and gauche when he wields his convention- and status quo-smashing sledgehammer doesn’t mean that his targets don’t deserve it.

D. C. Alan ’86

Washington, D.C.

For a perspective on how we arrived at our current climate of rejecting expertise, allow me to recommend an article by Steven Brill (“How My Generation Broke America,” Time, May 17, 2018). To summarize the argument of that article, and with apologies for any misunderstanding I may convey about Mr. Brill’s views, the experts of the last 50 years have spent a disproportionate amount of time, effort, and, yes, expertise in enriching and protecting themselves and their employers.

For example, the rewards for corporate attorneys have vastly outpaced those for attorneys who choose to serve lower- and middle-class individuals or the public interest. Consequently expertise has flowed away from the latter and to the former. Investment expertise, similarly, has flowed away from helping the public avoid destitution and toward creating financial instruments for specialized corporate use. When those instruments failed, the public was left to their own devices but the experts’ employers were bailed out.

Consider the impact of expertise on the public. Dr. Nichols believes that the failures of expertise are “spectacular but rare,” but the victories of expertise are a two-edged sword. The creation and marketing of opioids was a victory for Big Pharma but a tragic failure for many thousands of addicts. The invention of labor-saving devices was a victory for manufacturers but a failure for the displaced machinists. Collateralized mortgage obligations were a victory for investors who held them, at first, but a failure for those whose homes were foreclosed and under water.

Where will it end? The Republic has survived far worse, but only when it was forged in the crucible of an existential threat that extended to the elite and the 99 percent equally. In war and economic crash, the elite and the plebe were in the same foxhole. A modest proposal: universal two-year national service where the elite would at least be working side by side with the 99 percent toward common goals.

Steven Law ’71

Windsor, Conn.

Contraception and Abortion

The May-June issue included a letter from Doug Kingsley (pages 4 and 6), referring to “…bullies in Washington who weaponized the IRS against patriots and forced the Little Sisters of the Poor to offer abortion coverage [Editor’s note: The issue was coverage for contraception.] against their religious convictions.”

The bracketed editor’s note is at best disingenuous. The Affordable Care Act required coverage, under 2011 Health Resources and Services Administration guidelines, for all FDA-approved contraceptive methods [77 FR 8725]—however these include morning-after pills like Plan B® and ella®. Interim final rules that became effective in 2017 noted that FDA “includes in the category of ‘contraceptives’ certain drugs and devices that may not only prevent conception (fertilization), but may also prevent implantation of an embryo, [including] several contraceptive methods that many persons and organizations believe are abortifacient—that is, as causing early abortion—and which they conscientiously oppose for that reason distinct from whether they also oppose contraception or sterilization” [82 FR 47792].

Peter Jacobson ’75

Livermore, Calif.

Yesterday’s (Sexist) News

Cute sexist quips aren’t cute. “Commencement-week protest [in 1973]..., meanwhile, shifts from politics to plumbing as women distressed by the general shortage...of toilet facilities for their sex stage a protest…” (Yesterday’s News, May-June, page 20). That this quotidian problem for women required a protest for it to be addressed, in fact required political action, is a reflection of the pervasiveness and subtlety of sexism.

In the recent movie Hidden Figures the black woman who calculates John Glenn’s trajectory has to run across the NASA campus in the rain to use a segregated bathroom. In the movie Kevin Kostner, the head of the space program, fixes the problem with a sledgehammer to the restrictive signage.

If the problem at Harvard had been addressed by Derek Bok wielding a sledgehammer against restrooms designated as men’s, perhaps we’d look back with more inclusive bravado and less bemused condescension.

John Craford ’68, A.M. ’69

Cape Elizabeth, Me.

Editor’s note: The point isn’t to be cute or demeaning, or to justify sexism. It is to show the kinds of language, policies, and attitudes pervasive at the time. The review of Hanna Gray’s memoir in the same issue (page 72) indicates how recently things were outrageously deplorable for women at Harvard—so people will remember and learn from that.

THIS IS A rain-drenched complement to the piece on Hanna Holborn Gray (“The Academic Heights,” page 72) in the May-June issue.

When my wife, Helene S. Shapo, M.A.T. ’60, was a graduate student in 1959-1960, she was working on a research project that required microfilm located in the basement of Lamont. It was pouring when Helene approached the front door of the library. She was refused entry on grounds of her gender and told that she had to go around to the back to gain entrance, which required a further drenching. Of course there were women in the main part of the library, doing various tasks like shelving books. Helene notes that as a Smith graduate, she was used to having full access to the library.

Marshall S. Shapo, A.M. ’61, S.J.D. ’74

Vose Professor of Law

Northwestern University School of Law

Evanston, Ill.

Rescuing Scholars

Dr. Hanna Holborn Gray is an unfaltering champion of higher education whose perseverance reflected not only that of the ambitious, educated women of the time, but also that of her father and his colleagues, refugees of academic persecution.

The Institute of International Education (IIE) established the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars in 1933 in response to persecution and threat of imprisonment of scholars by the Nazis. The Emergency Committee rescued more than 300 scholars and matched them with American university hosts, who generously offered them safe haven, both for the academies and for their lives. Among those rescued in that first year was Dr. Gray’s father, Hajo Holborn, the Carnegie professor of international relations and history at the Hochschule für Politik in Berlin.

Harvard played a crucial role in the facilitation of the Emergency Committee, hosting many scholars in need during the crippling of German, and later European, higher education in the 1930s and 1940s. That legacy continues today. Harvard is a key partner of IIE’s Scholar Rescue Fund (IIE-SRF), the modern-day iteration of the Emergency Committee; IIE-SRF provides fellowships and support for displaced and threatened scholars from all over the world. Since 2003, Harvard has hosted 26 IIE-SRF scholars from 19 countries and our collaborations continue.

Allan E. Goodman, Ph.D. ’71, M.P.A. ‘68

President and CEO, IIE

New York City

Editor’s note: For more information on a related topic, see “Scholars’ Haven,” May-June 2006, page 72.

Lawrence Bacow

I enjoyed reading the laudatory introduction of Lawrence Bacow as Harvard’s new president (“Continuity and Change,” May-June, page 14). His academic pedigree, belief in the mission of the University, and overall humanity augur well for the future stewardship of Harvard.

Nonetheless, I was troubled by the new president’s quote, as reported in the magazine, that the science of climate change is “set.” Surely, someone who has devoted his career to academic freedom and inquiry would acknowledge that the science of anything is never “set.” Rather, it should represent an unrelenting pattern of analysis, testing of hypotheses, and interpretation of results, leading to further refinement and understanding of the problems being studied. At its essence it is a process of questioning.

In setting the tone for his presidency, my appeal to President Bacow would be to reinvigorate the sensibilities of curiosity, openness, and appetite for discovery that can make an academic community so vital. My worry is that those boundaries have contracted on the Harvard campus in recent years, and my wish is for the opposite.

Brad Keller, M.B.A. ’88

Lake Bluff, Ill.

A “Deplorable”’s View

Re the identification of Angela Davis in the note about the acquisition of her papers (Brevia, May-June, page 25) as “feminist and countercultural activist”: “fake news” involves what is left out as much as what is included. And the Radcliffe Medal to Mrs. William Clinton is the kind of thing a “deplorable” such as myself expects from Harvard these days.

John Braeman ’54

Champaign, Ill.

The Electoral College

Lincoln Caplan (“America’s Little Giant,” January-February, page 56) was spot on when he called the Electoral College “obsolete.” Worse than that, it prevents us from having fair national elections for president and vice president.

The Electoral College today functions as nothing more than gerrymandering at the national level. Stick most of the voters of one persuasion in a few highly populated states, where they win by large margins, concede those states, and then win most of the others with fewer total votes, and sometimes by only a few votes. Voters in gerrymandered states are essentially disenfranchised; they are in the majority, but their votes don’t count. The will of the majority is thwarted, and a minority of the people can maintain political control over the majority.

The Constitution was a compromise, as anyone knows who has studied its history. It is a living document, meant to adapt and change as times change; Madison himself acknowledged that. It was a huge achievement, the best that could be done under the circumstances, and was certainly a big step above having a king who owned everything. Without national unity, the original 13 colonies would have been vulnerable and could have been easily overwhelmed by rapacious European powers (it almost happened in the War of 1812). Many deals needed to be struck to convince all 13 colonies to sign on. The Electoral College was one of those deals.

Another was having two senators from each state, regardless of population. This gave states with smaller populations, many of which happened to be “slave states,” a huge advantage in Congress. One of the main reasons the Republican Party was formed was precisely to address this imbalance of power. By 1850, the slave states had about one-third of the population of the country, and about one-half of those people were slaves, but because of the two-senator rule, they had virtual parity in the Senate. If slavery were extended to the new states entering the union from the West, that advantage would be locked in, and so would slavery.

Abraham Lincoln ran for president on a platform that specifically addressed this question. He believed slavery was wrong, but above all he wanted to keep the Union intact. Many of his fellow Republicans wanted to abolish slavery outright, but Lincoln hoped that by simply limiting the spread of slavery and not outright abolishing it, that practice would eventually die a natural death, and the slave states would stay in the Union. It did not work. Our country fought the biggest war in the history of humanity up to that time, and suffered the most American casualties of any American war, approximately 620,000 soldier deaths, the equivalent of 6 million in today’s population, plus countless “collateral damage” from starvation and disease.

Today, slavery is gone, women have the vote, and the 50 states are no longer separate colonies needing to be lured or cajoled into a coalition, lest they be overwhelmed by foreign powers. But the two-senator rule still gives the minority of the people an advantage over the majority of the people in the Senate. Witness what happened in the eight years of the Obama presidency. One man, Mitch McConnell, a senator from a relatively low-population state, was able to stymie the will of the American people who voted for Obama, and his political agenda, twice with significant margins. He was able to stymie a constitutionally allowed nomination to the Supreme Court and facilitate the appointment, on party lines, of a candidate less reflective of the values of most Americans. This arrangement still gives smaller states plenty of power to exercise their rights as states.

Those who claim “states’ rights” as a good reason to keep the Electoral College are missing some major points. A president elected by a minority of voters can use the tremendous powers of the presidency to override the will of the people of the various states. For example, in 2018, 70 percent of Americans, and majorities in most of the states, want a clean DACA bill, but the president elected by a minority, with help from a gerrymandered Congress, has so far made that impossible. Two-thirds of Americans live in states that have voted to legalize the use of cannabis recreationally and/or medically, but a president elected by a minority has appointed an attorney general from the minority party who is trying to override the will of the people in those states. The same could be said for women’s reproductive rights, where there is tremendous pressure from the minority party to override the will of states where large majorities favor these rights. And states along the shores of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans do not want drilling for oil, with the inevitable spills, right off their shores, but the minority president can override their will. So much for “states’ rights.”

One might make a plausible argument that there should be an institutionalized venue for states to assert their interests as states, and currently that venue is the Senate. But the senatorial advantage should not be transmitted over to the one election we have that involves everyone at the national level, the election of a president and vice president. Today in a national election it takes a supermajority of votes to overcome that advantage; a majority is not good enough. In 2016, a majority of more than three million was not good enough. There was a built-in “thumb on the scale.”

The president and vice president are supposed to serve all the people, not just the people of some of the states, and certainly not just the people from a few “swing” states. It is time to acknowledge that we are, in fact, one country, and when it comes to the only elections we actually have at a national level, all the citizens need to have an equal say. The first three words of the Constitution are “We the People,” not “we the states.”

Michael Traugot ’66

Placerville, Calif.

Postwar German Art

I disagree with Sophia Nguyen’s conclusion in her review, “ ‘Inventur’ Revisits Postwar Germany” (February 9, 2018), of the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue, Inventur: Art in Germany 1943-1955 previously on view at the Harvard Art Museums. I do not think that the particular artists mentioned merit a review that either paints them as heroes in the German Romantic tradition or as victims for the act of simply having to survive, by being willing to use miscellaneous materials as a basis for their art, thus allowing them to continue to practice their craft during wartime. This exhibition is an inventory of artwork created during the final years of World War II and the immediate postwar period. They have not been previously recognized outside of Germany.

Quoting from the exhibition catalogue, Nguyen acknowledges the following: “By necessity, these are artists who were racially and politically accepted (or at least tolerated) by the Nazi regime.” She also asserts that the exhibition “raises questions about complicity with totalitarianism.”

Yet she does not develop this theme nor do the involved artists prior to the war or its aftermath.

Those artists whose work is shown in this exhibition represent only one segment of German society, a part of a Nation State which, Nguyen acknowledged, had a totalitarian form of government. Yet she makes no comment about the fate of those other artists who, by implication, were not “racially and politically accepted.”

Nguyen commends the artists in this exhibition for their resourcefulness and ingenuity in the creation of art in a totalitarian society during wartime conditions. She states, “Even without government approval to make and show pieces, and with resources dwindling, artists found ways to work. Some found means of creative expression under the guise of practical aims…”: for example, one artist who worked in a lacquer factory and was able to pursue artistic goals. He made “a series of panels demonstrating different lacquer effects.”

Nguyen also states that the artists had been in a state of “ ‘inner emigration,’ their art turning inward and private.” Neither Nguyen, nor the exhibition tag (which makes much of this attempted adaptation to circumstances), nor the catalogue, elaborates on its significance as a survival mechanism, or possibly, as a retreat from the political environment in which the artists found themselves.

The complaints of these artists, who had the good fortune of having survived, were to some extent about minutia, for instance, the dwindling of art supplies. The catalogue paints a more vivid picture of these German artists’ as suffering (e.g., destruction of a lifetime’s artwork due to bombing by the Allied forces of their city, or some with forced relocation) without contemplating who initiated the war.

In discussing the artwork, Nguyen points to one piece that was not intended by the artist for public consumption (which was critical of the current German regime), yet she states that other works, for example, ink sketches of the ruins of the city of Dresden “are seemingly straightforward documents of violence and destruction.” There is no mention of the repeated German bombings of London and other English cities. The exhibition tags, like the catalogue, suggest a moral equivalence (e.g., a photograph of corpses in the center of the city) is being drawn between the destruction caused by the Allied bombings and by Germany, without regard to who initially instigated the destruction of cities.

The catalogue has subtle criticism of the Allies: for instance, “an overfilled American prisoner of war camp,” with no mention of how the German government treated others during the war.

Nothing that I have stated above is news. The director of the Harvard Art Museums acknowledged to another university news source, the Harvard Gazette, that “there are some very controversial conversations to be had around this topic.”

If so then, the question is the following: Why the silence at Harvard?

The Harvard Art Museums are a teaching facility. Undergraduates crowded into Menschel Hall on the night of the artist’s talk at the time of the opening of the exhibition. These students are too young to have experienced World War II and its aftermath. The speaker at this lecture, a famous postwar artist, the only surviving artist whose work is in the exhibition, pays a nod to the German-initiated Holocaust, citing the work of Gerhard Richter, a living artist. This was Richter’s famous photograph of his uncle “Rudy” in an SS uniform. This photograph suggests that Germans were introspective after the war, at least Richter was, and, that the young cannot be blamed for the actions of their elders. How many offspring were as introspective as Richter and the artist who spoke at the lecture?

While one can recognize aspects of art for its own sake, such as the “gems” brought out for this exhibition, one must acknowledge the unspoken environment in which these works of art were created.

Questions remain: What are the lessons for this exhibition? Are these works of art to be celebrated without fully describing the milieu of the society in which they were produced?

Barbara W. Tanzer

Newton, Mass.

Solzhnitsyn at Harvard

Forty years ago, I went to Cambridge just to hear him speak (see “Solzhenitsyn in My Inbox,” by Wanda Urbanska, May 21, 2018). Originally I was not going to bother to attend Harvard’s Commencement in June of 1978 just to pick up my master’s degree in political science from the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, department of government. I already had obtained my Harvard law degree in June of 1976 when Daniel Patrick Moynihan spoke. (LOL on that!) By then I was working as a tax lawyer for a downtown Boston corporate law firm, making a lot of money. I was also getting ready to move out here in order to start my chosen career as a tenure-track assistant professor of law at the University of Illinois College of Law in Champaign: no point missing a day’s worth of pay for another Harvard Commencement. (Later, in 1983 I would tell Harvard to put my Ph.D. in the mail, skipped that Commencement, and never bought their over-priced Harvard Ph.D. regalia that makes you look like a Roman Catholic cardinal.)

Then Harvard announced that Solzhenitsyn had been lured out of his exile and compound in Cavendish, Vermont, in order to give its Commencement address. Kudos to Harvard! A unique intellectual event of monumental significance! So of course I immediately claimed my Commencement ticket and decided to chuck a day’s worth of pay that I could have readily used to smooth my transition and relocation to academic life here.

My Russian teacher did the translation. My teacher, mentor, and friend Ned Keenan (RIP) sat on the podium right near Solzhenitsyn. It was not Solzhenitsyn’s intention to “school” Harvard or the United States of America. Rather, he spoke with a good deal of sadness and anguish in his voice. As correctly pointed out, he offered his comments as a “friend”—not as a schoolmaster. That is precisely how at the time I personally received and understood what he had to say. I respectfully submit that is the appropriate way to read and re-read Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard address today.

Francis A. Boyle

Professor of Law

University of Illinois College of Law

Champaign, Ill.

Erratum

“Visiting Hours” (Montage, May-June, page 66) erroneously reported that Jack Lueders-Booth, Ed.M. ’78, was 30 when he decided to pursue photography full-time; he was 35.