The diagnosis of depression rests entirely on symptoms: extreme self-criticism and suicidal thoughts, loss of interest in activities that were once fun and satisfying, changes in sleep patterns and appetite. If these symptoms disappear, a patient is considered fully recovered (although susceptible to relapse). But in a recent study, professor of psychology Jill Hooley found that the brains of recovered patients still show distinctive activity patterns--even though the subjects reported feeling normal.

Hooley specifically sought to examine the way subjects’ brains processed criticism. Using the relatively new technology of functional magnetic resonance imaging, she aimed to update an earlier finding from her own 1976 study, which established that patients who’d recovered from depression were more likely to relapse when living in a highly critical family environment. She and colleagues therefore imaged the brains of subjects listening to criticism from their own mothers in the form of 30-second recorded messages. (Each of the study subjects--11 women with a history of depression and 12 without--heard a total of six messages: two critical, two complimentary, and two neutral as points of comparison.) By capturing the emotional immediacy of criticism from a family member, the study approximated the real world more closely than is typically possible in the lab.

Precisely because of that immediacy, the researchers took care to minimize the chance of psychologically wounding participants or poisoning mother-daughter relationships. The mothers received particularly detailed instructions for the negative messages: the criticisms had to be concerns they had previously raised--“We didn’t want anyone to be broadsided by a new criticism,” says Hooley--and had to be relatively benign. “The last thing we wanted was for mothers to be saying things like, ‘You’ve ruined my life. I wish I’d never had a child,’” she adds. “That’s not criticism--that’s extreme hostility.” The negative messages’ topics included tattoos and piercings; lack of faith in God; failure to send thank-you notes; and being inconsiderate and untidy.

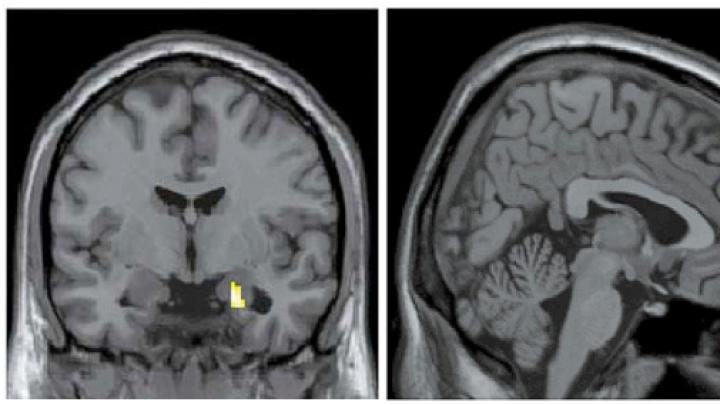

In the images that resulted, the researchers could see that the brains of the formerly depressed subjects processed the critical comments in a markedly different way than the brains of the subjects who’d never been clinically depressed. The images highlighted three brain areas that seem to work together to regulate emotional responses and which had been flagged in previous research as areas of interest to the study of depression. As the formerly depressed subjects listened to the criticism, they showed significantly less activity, compared to the control group, in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a late-developing area involved in planning and working memory, and in the anterior cingulate cortex, which lies deeper in the brain (wrapped around the corpus callosum that connects the two hemispheres) and is involved with a wide variety of functions including assessing the motivational and emotional content of stimuli; response selection; and problem-solving. Instead, their brains showed increased activity in the amygdalae, which lie deeper still in the brain and form part of the limbic system.

What seems to be happening, says Hooley, is that criticism activates the amygdalae in the brains of those who have been depressed, perhaps tripping a primal emotional response and bypassing the more analytical response seen in the brains of subjects with no history of depression. Yet when asked about their mood as they listened to the critical remarks, the formerly depressed subjects didn’t report feeling worse than the control group. They had exhibited no symptoms at all for some time (six months as a minimum to qualify for inclusion, and 20 months on average); they acted normally and felt normal. But their brains told a different story and, says Hooley, “They had no idea this was happening.”

A similar pattern manifested as the subjects listened to the complimentary remarks. Amygdala activation was absent in both groups (understandable, says Hooley, because such activation is often an indicator of fear), but the controls showed activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, while the formerly depressed subjects did not. “It’s as if they aren’t getting the full benefit of the praise,” she says. (Responses to the neutral comments followed a similar pattern.)

She sees an application for her methods in predicting depression risk: during the study, some members of the control group exhibited brain activity patterns resembling those of the formerly depressed subjects. “It makes you wonder what’s ahead for those people,” she says. To find out, she is applying for funding for a prospective study that images subjects’ brains and then follows them over a period of years to see whether brain activity patterns predict depression.

Hooley says her results (published in February in the journal Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging) raise the question of whether it is possible to rewire the brain to process criticism in a manner that is more deliberative and less visceral. Although more research is needed, she suspects future findings will affirm the effectiveness of cognitive therapy--already in use to treat depression--because of its focus on helping patients retrain their brains to respond differently to difficult emotional situations. Absent the ability to protect patients altogether from the “low-grade punches to the brain” of criticism, says Hooley, “we wonder whether we can teach them to be more resilient.”