Though virtually unknown in mainstream American culture, Li Shizhen (lee sher-jen) is virtually a household name in China. A kind of patron saint of Chinese herbal medicine, widely lauded by historians and practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), he is widely represented in popular and scholarly media. Movie star Jet Li recently named him one of his personal heroes, and he has been the focus of comic books, popular songs, TV dramas, and films. This is all rather impressive for a sixteenth-century doctor who lived, worked, and died in south China in relative obscurity.

Li was born in an area now known as Qichun, in Hubei Province. His father had big plans for the boy, but young Shizhen was sickly and for various reasons kept failing the civil examinations that would have brought him (and his family) a prestigious post in the state bureaucracy. Luckily, he had a backup: his grandfather had been a traveling doctor, his father was a doctor, and that appeared to be his career path as well. He studied the medical classics, apprenticed with his father, treated local townsfolk, and eventually became successful enough to secure some brief yet high-profile positions in the capital and to befriend a few influential scholars. He wrote several short medical treatises on everything from mugwort to pulse diagnosis, composed some poetry, and made a decent living for himself, his wife, and his sons.

But this is not what put Li’s face on the walls of medical colleges or his name in the speeches of Mao Zedong. None of it would have mattered had he not spent the last half of his life researching and writing an enormous book that became his magnum opus, the Bencao gangmu (ben-sow gong-moo)—an encyclopedic work in the tradition of bencao (materia medica) literature, which includes works explaining the qualities of the various substances used in making medical drugs: plants, animals, stones, clothing, household implements, and assorted other materials. One of the most ancient forms of medical writing in China, a bencao was often composed or revised at the behest (and with the financial backing) of an emperor. Instead, Li took it upon himself to spend decades traveling—interviewing hunters and fishermen and local healers—reading omnivorously, and trying various treatments for his own patients until he had compiled enough information to satisfy himself that it was time to sit down and compose an encyclopedia of his own. He spent 10 years writing his enormous book, and perished before it was published. Only due to the hard work, editing, and perseverance of his sons and grandsons was the Bencao gangmu finally printed in 1596, three years after his death.

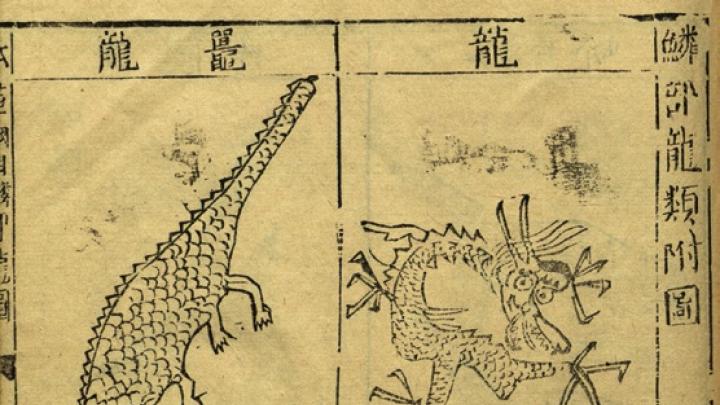

But what an amazing book it was! The largest and most complete work on materia medica of its time, the Bencao gangmu contains 52 chapters of descriptions, stories, poems, histories, and recipes for how to use and understand everything from fire and mud to ginseng and artemisia, turtles and lions, and even human body parts as medical drugs. Li was a man obsessed: convinced that the only way to properly use something as a drug was to understand as much as possible about it, he stuffed everything he could find into his bencao, from as many different books as he could get his hands on. He experimented both on the creatures around him and on himself, recording his experience getting “half-drunk” in local bars and trying out remedies on patients to test the hypotheses of other doctors, poets, and scholars. In the pages of his book, one can find prescriptions for dragon bone, stories of corpse-eating demons and fire-pooping dogs, instructions for using magic mirrors, advice for getting rid of locusts, and recipes for excellent fish dinners.

Of course, we don’t hear much about the dragons and demons anymore. As with most historical icons, Li’s name and story have been resurrected many times since his death to serve many different purposes. In posters and films, he was recast in the image of a wandering people’s doctor in the 1950s. As a result, most people today know of him as the father of Chinese pharmacy, a humble doctor who recorded the herbal knowledge of the people around him and preserved it for posterity. His image consecrates the walls of many TCM colleges in China, and scientists continue to test his recipes and translate his sixteenth-century pharmaceutical insights into the drugs and terminology of modern biomedicine. Modern authors often attempt to confirm Li’s early medical use of plant, animal, and human-based medicines (from toads to ephedra), his clinical practices, and his prescriptions for drugs to treat epilepsy, gynecological diseases, and many other maladies.

Li might have been amused by such efforts to standardize and normalize his ideas and practices. There wasn’t one correct remedy for an illness, as far as he was concerned, and he recorded his thoughts of ghosts, phoenixes, and miraculous transformations in the same pages as his recipes for ginseng and chamomile. As he reminded aspiring doctors, there are often no clear answers when attempting to understand nature. We can only keep trying, learn from our mistakes and observations, and be open to phenomena and stories we might initially consider strange or impossible. He ended his book with a statement to that effect, and to the end of his life he struggled to make the statement known.

![From <i>Li Shizhen: Weida De Yaowu Xuejia</i> [Li Shizhen: Great Scholar of Medical Drugs] (Tianjin: Zhongsheng Shudian, 1955), 60. Needham Research Institute, Cambridge, England Li prepares to dissect a pangolin, from a popular pamphlet, <i>Li Shizhen: Great Scholar of Medical Drugs</i> (1955).](/sites/default/files/styles/topic_teaser_mobile_d7/public/img/article/1209/p32_01.gif?itok=fHW4Ob6Q)