This is an English garden, to be sure, with plantings arranged to mimic natural settings such as ponds or meadows or woodlands—very unlike the geometric, clipped formality of French or Italian gardens. “I must congratulate you—you’ve built an English garden outside of England,” observed an elderly British visitor a few years ago. But this isn’t just another well-tended bower: in 2008, the Smithsonian Archive of American Gardens added the property to its national archive, and on “open days,” organized by The Garden Conservancy, hundreds of visitors from neighboring states have admired its riches.

The splendid garden fills a verdant acre at the home of Ilona Isaacson Bell ’69, RI ’89, and Robert Bell, Ph.D. ’72, in Williamstown, Massachusetts. (She is the main gardener, he an actively engaged appreciator; a few hours a week of hired help aids with weeding and other maintenance.) The house is a century-old carriage barn remade into a residence, which the Bells acquired in 1978. Both teach English literature at Williams College, and appropriately enough, their cultivated landscape has several embedded literary references. A line from Andrew Marvell’s poem “The Garden” (“A green thought in a green shade”) surmounts a wooden window frame in the center of things; not surprisingly, Ilona Bell specializes in Renaissance poets like Marvell, John Donne, George Herbert, and Mary Wroth. The Bells named a stone statue of a seated lion “Aslan,” after the central character in The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis—also a Renaissance lit scholar; another statue depicts Titania, the queen of the fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. And one of the garden’s “rooms” is a white garden (based on white foliage and flowers) designed in tribute to a room at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent, England, the creation of Vita Sackville-West, a lover of one of Ilona Bell’s favorite authors, Virginia Woolf.

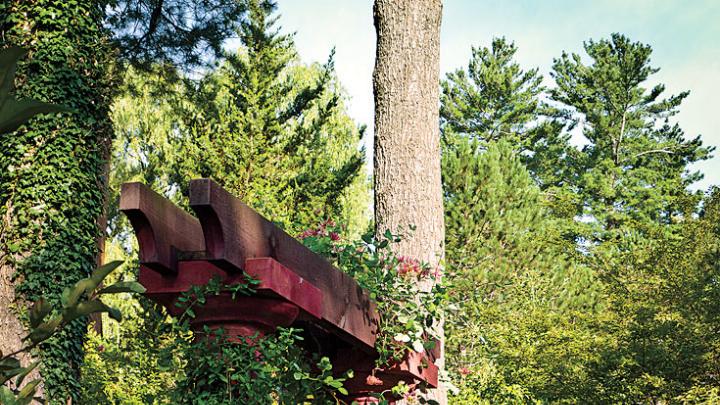

Seeing Sissinghurst in the 1970s “was a revelation,” Bell says. “The complexity of the design—each room had a different mood, tone, color scheme, architecture. In England, a garden room is an enclosed area, often surrounded by walls that can be eight or 10 feet high. Here, I’ve tried to create a distinctness to each area.” Rather than brick walls or high clipped hedges, as at Sissinghurst, she used a pergola, for example, to separate her extensive kitchen garden from the neighboring water garden, where goldfish swim among water lilies and lotuses in a small pond piped to allow a burbling flow of water. A folly composed of a few “ruined” columns defines another space (“I call it ‘Bob’s folly,’ ” she explains, “but he calls it ‘Ilona’s folly.’ ”) The wooden window, a classic garden element, helps frame the central space, and supports climbing vines.

As in many English gardens, the Bells grow various trees (including a gingko and a weeping beech), shrubs, and perennial flowers. Their “hot border” features flowers selected for their deep warm hues like red, gold, and fuchsia; Bell studs the border with annuals like canna, perilla, and red salvia to keep the heat turned up as the seasons change. The garden is constructed so that there is always something in bloom in every space. But with thousands of plants, it’s challenging (despite an inventory on Bell’s computer) “to keep it all in your mind—to remember what’s blooming on May 1, or June 15, and how they all go together.”

As someone immersed in the literary arts, Bell readily sees the garden as an art form—created in partnership with Mother Nature and involving a temporal dimension, over seasons and years. It satisfies the senses of sight, sound, touch, smell, and even taste (the Bells eat some flowers, as well as their homegrown vegetables). She has explored its dimensions in a lengthy essay, “Superego in Arcadia: Gardening as Performance,” which appeared in a special issue of The Southwest Review in 2010. “The trouble with the garden as art,” she explains, “is that as soon as you get it the way you want it, something gives up the ghost. One of our hemlocks got diseased and had to be removed—that changed everything.”

She does have some advice, though, for those seeking a perennial philosophy. “If you want a garden to look good,” she says, “you have to pay more attention to the leaves than the flowers, as they are there all season long.” No matter the season, the endless project never loses its allure. “I like the imaginative complexity of the challenge it poses,” she says. “There are so many elements in play.”