The late filmmaker Richard Rogers '67, Ed.M. '70, who died of cancer in 2001 at age 57, was a passionate and productive artist. His documentary films range from Quarry (1970), a slice-of-life look at youths diving, swimming, and lounging around a beautiful abandoned rock quarry in Quincy, Massachusetts, with a late-1960s rock soundtrack and looming shadows of Vietnam, to Pictures from a Revolution (1991), which follows photographer Susan Meiselas, Ed.M. '71, as she returns to Nicaragua 10 years after documenting the Sandinista overthrow of Somoza. There were literary portraits like his 1988 William Carlos Williams, done for PBS; quirky films like 226-1690 (1984), a "minimalist soap opera" drawing on a year's worth of messages on Rogers's answering machine; and the historical re-enactment of A Midwife's Tale (1996), based on the diary of a Colonial midwife that 300th Anniversary University Professor Laurel Thatcher Ulrich expounded in her 1990 book of the same name.

Yet there was one film Rogers was never able to finish, despite 20 years of shooting and collecting footage, much of it centered on his own family and the Hamptons town of Wainscott, where they had a summer house. It was left to his student Alexander Olch '99 (Rogers taught filmmaking for many years at Harvard and was director of the film Study Center) to create The Windmill Movie from the miles of uncut film and video left behind. "There was a very good reason why he let this one go," says Olch. "Dick completed 18 films, but this was the only one that really gave him trouble, because the subject was on the other side of the camera." In fact, Olch's most basic decision was figuring out that the film was about Rogers, not Wainscott; it's a choice Rogers himself, who constantly fretted about being too self-indulgent, was unable to make.

The film, which opens at the film Forum in New York City on June 17, with national release and HBO broadcast to follow, tells its subject's troubled life story. It's a collage-like portrait of "a compellingly charming and vivacious guy, a WASP Woody Allen," says Olch. The nonlinear narrative skips around among decades from the 1920s to the present; the director tracked down people who had footage of Rogers and shot new footage himself, including scripted scenes with actor Wallace Shawn '65, the late filmmaker's friend. Olch wrote and read the voice-over narration, taking on his mentor's persona. He compares the movie's structure to a Russian nesting doll.

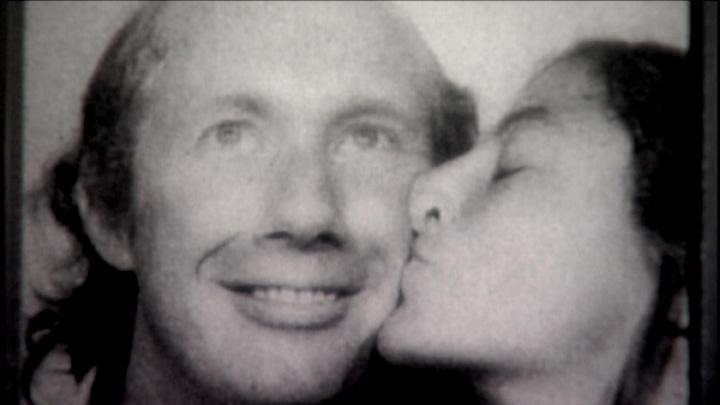

Indeed, The Windmill Movie unfolds on many levels. There's a summertime portrait of a wealthy Hamptons community, with tennis, swimming pools, private beaches, and swank cocktail parties on a lawn with a small windmill, which gives the film its title. There's a dysfunctional-family narrative fleshed out by interviews with Rogers's dyspeptic mother and patrician father, who shot film footage in the 1920s that Olch includes. (He marvels that it took "three generations to make this movie.") There's an absorbing portrait of Rogers's massively self-doubting, self-critical persona, played out within his enviable, well-appointed lifestyle and hectic, nearly farcical sexual and romantic life. (His relationship with the celebrated Magnum photographer Meiselas spanned more than 30 years, but, as the film shows, there were passionate interregna with other partners; the couple finally married near the end of Rogers's life.)

Then there is the embedded meta-movie about filmmaking, including the very movie we are watching. We see Rogers filming Meiselas as she herself takes a photograph; there's a cut of Meiselas struggling with a huge microphone, recording the soundtrack while Rogers films a garden party. Many scenes find Rogers editing film at his console. We see Meiselas, who produced Olch's movie, unpacking old boxes of film--the very footage we have been viewing. Unsteady handheld shots add a home-movie feeling, as do the onscreen countdowns that partition sequences. "These are things you usually don't get to see as a viewer," Olch explains. "I want you to see the dust on the old film, to hear the crackles of the sound. It's supposed to feel unexpected and messy. Pulling the curtain back on that is a metaphor for pulling the curtain back on Dick Rogers and his story."

Olch made his first film in third grade and by middle school, he says, "I walked around with a trench coat and fedora, thinking I was Fritz Lang." He began work on Windmill by "doing everything correctly, making just perfect cuts," he says. "But it was so boring and so flat. I started looking at sequences I had rejected, and there seemed to be an energy in the reject pile; the movie's style sort of grew out of that, and began to convey the experience I had going through all these boxes of film."

The two filmmakers had bonded quickly as teacher and student; Olch first saw Rogers banging open a metal door into a Harvard hallway, "discoursing like a tweed-jacketed studio boss from the 1940s, tufts of red hair flowing from the sides of his otherwise bald head." Rogers's first words to Olch were, "Seventy-fourth Street. Collegiate," nailing both the home address and private school of his new student. (It turned out that the two men had lived in adjacent buildings on East 74th Street in Manhattan.) For two artists to join forces in this way may be unprecedented in cinema.

"Would that I could say there are ghosts or spirits where I will lurk," intones Olch as Rogers, facing death, "but there is only this, this movie where, just for an instant, I will be alive in this little world, this little séance of flickering light and no one, not even the heavens, can take that away from me." Shortly before Olch reads these words on the soundtrack, we see Rogers asking his wheelchair-bound father, who has lost some of his memory after a stroke, "Where do the memories go?" The Windmill Movie offers one, very personal, answer: they are preserved on film.