On display through September 30 at the Center for the History of Medicine are selected items from the papers and effects of John C. Rock ’15, M.D. ’18, and other items related to his work.

Rock, a professor of gynecology who taught clinical obstetrics for three decades at Harvard Medical School (HMS), is remembered for two landmark professional achievements, both grounded in the notion that women should have control over their own reproductive systems.

Rock (pictured at right) pursued these two tacks with equally intense conviction, said Margaret Marsh, Distinguished Professor of history at Rutgers University and coauthor of the 2008 biography The Fertility Doctor: John Rock and the Reproductive Revolution, at a March 26 symposium to mark the exhibit’s opening. Marsh said that Rock, a practicing Roman Catholic, believed couples should have as many children as they had means to support, but that they should also have the power to stop their families from expanding.

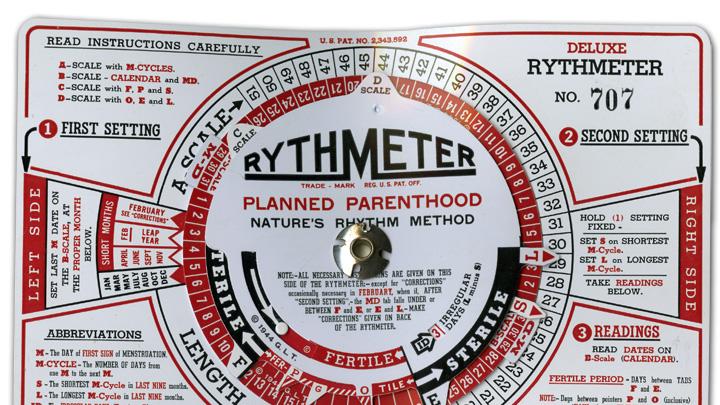

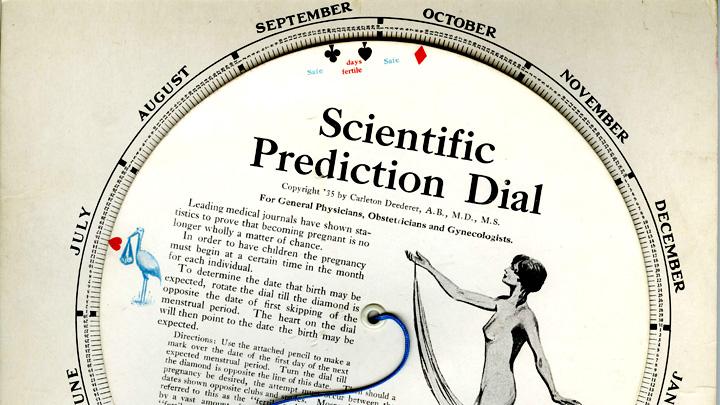

The image gallery includes two samples of family-planning devices from the days before the pill. Rock would have given the “scientific prediction dial” or a similar device to patients in his early days at the Rhythm Clinic, which he founded in 1936 at the Free Hospital for Women (now Brigham and Women’s Hospital). The Rythmeter (circa 1944) came with a more complicated set of instructions. At the time, the rhythm method was the only legal form of contraception in Massachusetts; it was at Rock’s clinic, in the early 1950s, that the first trials of hormone-based birth control took place. Rock advocated for the Food and Drug Administration to approve oral contraceptives (which it did in 1960), and for his church to change its position on birth control (which it did not).

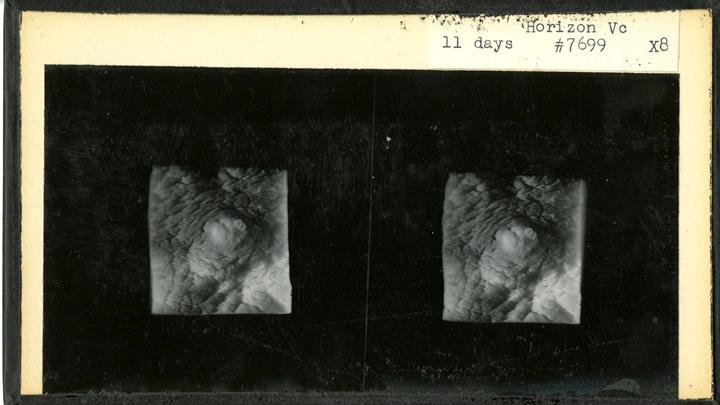

It was also in Rock’s lab that the first successful in vitro fertilization took place. In the image gallery is a photograph of the fertilized ovum from this experiment, which Rock conducted along with HMS colleague Arthur Hertig and laboratory assistant Miriam Menkin in 1944. Research in this area was later banned in the United States; the first in vitro baby, Louise Brown, was born in England in 1978. Since then, more than a million children have been born through this method.