In 2001, a research assistant at the Harvard Medical School-affiliated McLean Hospital noticed an intriguing pattern. One of her tasks was to escort study participants to and from a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine where they received brain scans. All of the participants had bipolar disorder and were depressed; the scans involved an experimental form of MRI that measured the effect of medication changes on their brain chemistry.

“The research assistant noticed that people came out of the MRI saying, ‘I feel much better,’” remembers Michael Rohan, an imaging physicist at McLean and lecturer at Harvard Medical School (HMS). The assistant shared her observations with the lab director, who consulted Rohan because of his expertise in the biological effects of electromagnetic fields (see “Magnetically Lifted Spirits,” May-June 2004, page 18). Why, they wondered, might this type of MRI trigger a sudden lift in mood?

Rohan immediately zeroed in on one particular waveform within the MRI because it pulsed at a speed and strength that he suspected could affect neuronal activity. He built a small prototype that produced the waveform, and colleagues then conducted a “forced swim test,” an animal study frequently used to test antidepressant medications. “Rats who have been given an antidepressant are more likely to swim or climb, instead of just floating and resting,” Rohan explains—and the rats exposed to his device swam and climbed more than the control animals. That suggested he had identified something significant.

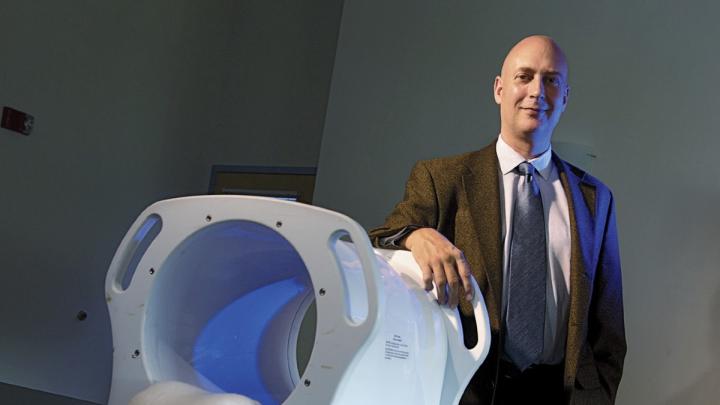

He then set to work designing a device to administer this low-frequency magnetic stimulation (LFMS) to humans, and received review-board permission to test it. The resulting machine looks a little like a miniature MRI machine, but is just 14 inches wide and can sit on a tabletop. The patient lies on a gurney, head positioned on a headrest; the device then slides down over the top of the head to about the eyebrows, “so that patients can see out,” Rohan explains. “We wanted people to feel very comfortable.”

In an article published this past summer in Biological Psychiatry, Rohan and his colleagues—including senior author Bruce M. Cohen, Robertson-Steele professor of psychiatry—describe their study of 63 people diagnosed with either major depression or bipolar disorder. People received either one 20-minute treatment with LFMS or a sham procedure, and took standard mood-assessment tests before and after treatment.

Both groups experienced immediate and significant improvement in mood: people in the placebo group showed a five-point improvement on a 17-point scale, while the treatment group had an eight-point improvement. That suggested, Rohan says, that researchers managed to “capture and separate out” the placebo effect. “People who come to McLean Hospital and get to try new technology feel better just because they walked in the door,” he says. Once the placebo effect has been stripped away, the remaining three-point change is similar to the improvements many people see after taking an antidepressant medication for six weeks.

This lag time is a troubling limitation of existing therapies. Current medications take at least four to six weeks to improve mood, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), though effective, require multiple treatments each week for a month or more before results appear. In contrast, patients who received one LFMS treatment felt better immediately, suggesting that the new option could help people in crisis. “We don’t have anything like that right now,” Rohan says. Furthermore, there are no reported LFMS side effects so far, whereas ECT can trigger memory loss and TMS often causes scalp pain.

The study wasn’t designed to examine how LFMS works, but Rohan hypothesizes that the device sends electric fields into cortical regions of the brain, where they may affect the dendrites, fibers that transmit information between neurons and play a key role in mood regulation. He stresses that the procedure needs further study; he’s now running a new trial of bipolar patients to determine how long the improved mood from LFMS lasts, and how frequently patients need the treatment.

Since his findings were published, Rohan has fielded frequent queries from families desperate to help loved ones with treatment-resistant depression. Given the need for new options, it’s surprising that it’s taken almost a decade to conduct initial studies on the LFMS device, but the National Institutes of Health “is reluctant to fund new discoveries,” Rohan explains. His current work is supported by grants from private foundations.

Rohan can’t offer concrete hope to families yet: “It’s really not the best choice to pin hopes on something that’s unproven so far,” he says. “But regardless of what happens clinically, this opens a new area into how to work with the brain.”