Lei Liang’s Xiaoxiang, a finalist for the 2015 Pulitzer Prize, is not the virtuosic tour de force one might expect of a saxophone concerto, a form showcasing technical skill. Liang’s starring instrument trembles, croons, and cries, traversing the unsettling musical landscapes. Expressions of grief come in waves and paroxysms that overwhelm the senses. The composition was named for a region in China’s Hunan Province and inspired by the story of a villager whose husband was killed by a local Communist official during the Cultural Revolution. With no means to seek justice, she wailed like a ghost in the forest behind his residence every evening—until they both went insane.

“This woman was wailing because words didn’t mean anything anymore,” explains Liang, JF ’01, Ph.D. ’06. “I wanted to find a way to give silenced voices like hers another chance.”

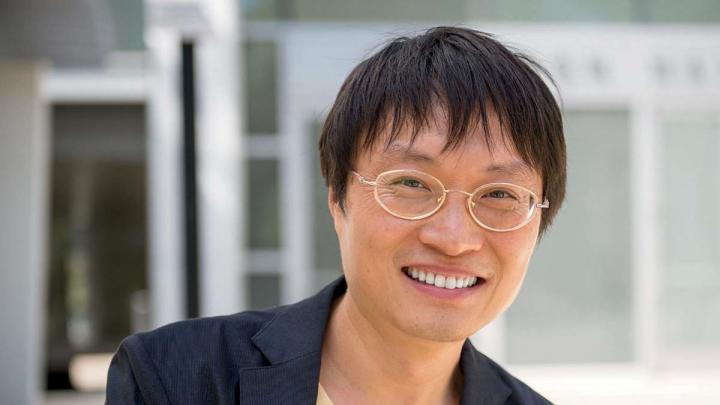

Xiaoxiang typifies his concerns with the politics of history—forgotten visions of the past, and those erased by the state—in his native China. He traces much of his own professional and creative course to one decisive event. “I’m here in America because of Tiananmen Square,” says the 43-year-old composer. “I was a protester.”

Under other circumstances, Liang might simply have been a prodigy: his upbringing in Beijing included piano lessons, and he started composing at age six, when he grew bored with his practice pieces. His mother, Liang-yu Cai, was the first Chinese musicologist to study American music in the United States. Liang says he “grew up” in the archives of the Music Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Arts where she taught, and where his encounters with field recordings gave him an early and unusual connection with China’s past. His father, Mao-chun Liang, a professor at the Central Conservatory of Music, pioneered the study of music during the Cultural Revolution; for a time after the unrest in Tiananmen Square, he was banned from publishing.

For two months, Liang protested in the square every day, until, as violence erupted, his parents locked him in his room; a family friend, concerned for his safety, made arrangements for the 16-year-old to study piano at the University of Texas, Austin, and attend a local high school on scholarship. Living with a family of fundamentalist Christians was a culture shock. “They had no radio, no TV,” he remembers. “I played piano for hymns during early-morning prayers.” But Liang’s relocation also began a process of reimagining China from outside its borders. Being allowed to roam the University’s library—the first he’d ever seen with open shelves—blew his mind.

“I’m here in America because of Tiananmen Square. I was a protester.”

Liang earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in composition from New England Conservatory (NEC), in Boston, while working in construction, walking dogs, and waiting tables in Chinatown. “I was famous at NEC for being one of the poorest students,” he says. “At McDonald’s, one hamburger was $3.25. I had $1 a day to live on, and many formulas for how to survive.” He kids that, even with today’s increased cost of living, “I still think it’s possible.”

At NEC, his principal teacher, Robert Cogan, instilled in him both thoughtfulness and a willingness to take his time in study. At Harvard for his Ph.D., Liang worked to “build his musical muscle,” developing the skills to materialize his ideas. It was a transitional period for the composition faculty. “Every semester, there was a new visitor: Harrison Birtwistle, Magnus Lindberg, Chaya Czernowin, Lee Hyla,” he recalls. “So I was able to take lessons from everyone and loved it.”

Yet the person he considers his single most important teacher was not a composer. Ethnomusicologist Rulan Chao Pian, an expert on Chinese traditions and one of Harvard’s first 10 tenured women faculty members, housed him for eight years and shared her personal treasure house of rare volumes and recordings with him. He states unequivocally: “I was reminded by Rulan Pian how wide this world is.”

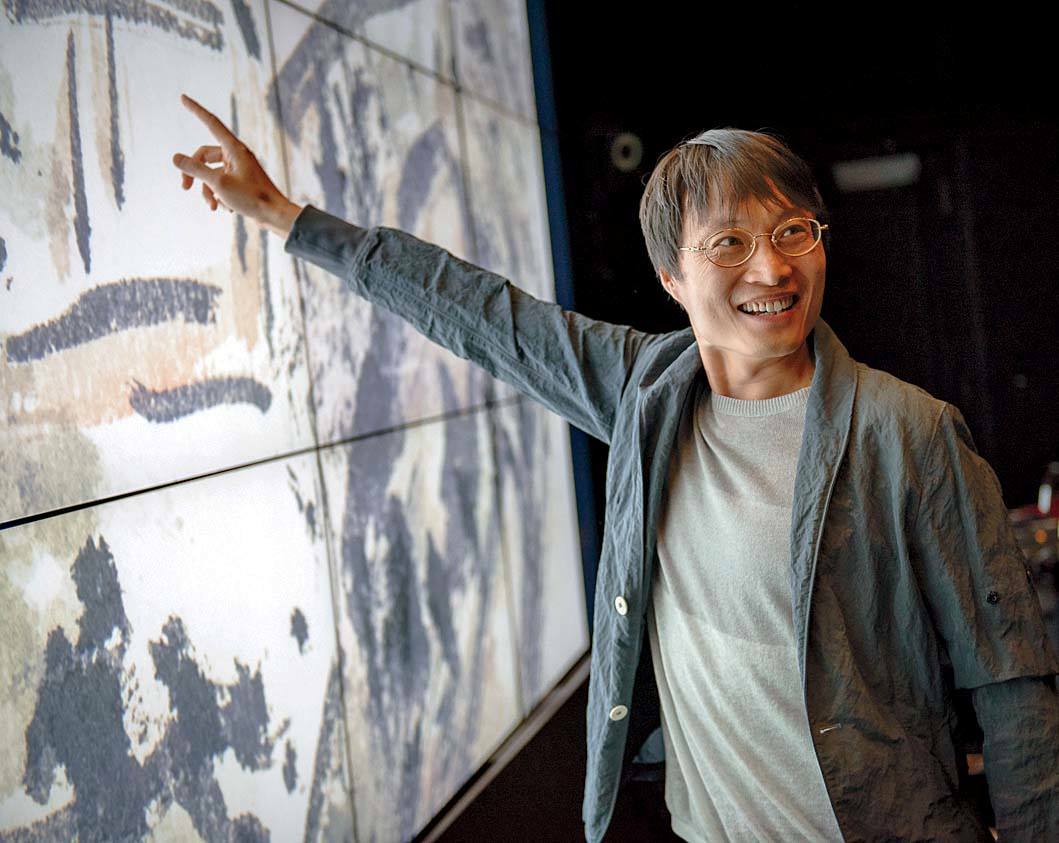

Liang with a scanned painting by Huang Binhong, the basis for a new orchestral work

Photograph by Alex Matthews/Courtesy of Lei Liang

Now Liang’s own breadth of knowledge and depth of understanding can be felt in each of his compositions. Cuatro Corridos, a chamber opera about human trafficking, drew from the stories he heard while waiting tables alongside undocumented Chinese immigrants. Hearing Landscapes, a multimedia performance in which a series of compositions accompany high-resolution, multispectral scans of landscape paintings by twentieth-century master Huang Binhong, allows Liang’s sense of geography to take on physical dimensions. Sound moves through a multichannel 360-degree space, taking its direction from the brush strokes of Huang’s calligraphy. A new commission based on these paintings, titled A Thousand Mountains, A Million Streams, will be premiered by the Boston Modern Orchestra Project in 2017.

While composing Xiaoxiang, Liang found a field recording of a folk melody from the area of Hunan where the murder and ensuing incident took place. He’s not usually one to borrow musical material, but “stories like these,” he points out, “have been part of Chinese literature since the Song dynasty, for over a thousand years.“ During a particularly striking moment in the concerto, that melody bursts forth, offering the listener temporary solace from the concerto and its anxious hauntings.