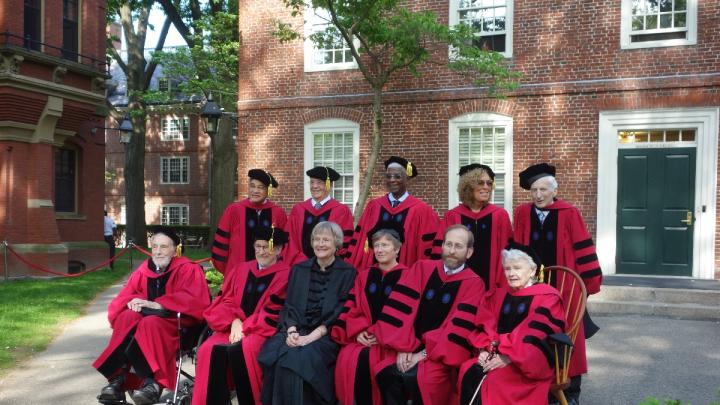

During the Morning Exercises of the 365rd Commencement, on May 26, Harvard planned to confer honorary degrees on six men and three women. Among them are:

- a lawyer who has pioneered cases ending discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation (now also a lecturer at Harvard Law School), and a moral philosopher known for her thought experiments (including a famous argument about a woman’s right to control her body and to terminate a pregnancy);

- a biographer of Langston Hughes and Ralph Ellison, an eminent African found-objects sculptor, and the former leader of Brazil;

- a film director, producer, and screenwriter whose credits include the 1997 historical drama Amistad, about a mutiny aboard a slave ship, and the preeminent historian of slavery and abolitionism; and

- a stem-cell scientist, and an astrophysicist who has made leading contributions to the study of black holes and the “cosmic dark ages”—the period after the Big Bang, before the universe was lit.

Two of the guests will add honorary doctoral degrees to their earned Harvard doctorates.

There is no obvious candidate this year for the role of honorand-performer, a recurring Commencement motif during President Drew Faust’s administration—à la soprano Renée Fleming last year, trumpeter Wynton Marsalis (2009), tenor Plácido Domingo (2011), poet Seamus Heaney reading his famous Harvard villanelle (2012), hugger extraordinaire Oprah (2013), and soul singer Aretha Franklin (2014). But perhaps Harvard Band members will riff on composer John Williams’s movie scores.

The honorands are listed below in alphabetical order, not in the order of conferral of degrees, except for filmmaker Steven Spielberg, who by custom, as guest speaker at the Afternoon Exercises, will receive his degree last during the Morning Exercises. For details on the conferrals, check back for coverage of the morning ceremonies later today.

El Anatsui, sculptor, Doctor of Arts. El Anatsui, born in Ghana in 1944 and based in Nigeria for much of his career, has become a preeminent West African artist, widely recognized for sculptures and shimmering, tapestry-like wall hangings made from found objects, such as the discarded tops, seals, and neck labels from bottles of distilled spirits. They have been compared to mosaics and kente cloths, changing with each installation.

A biography posted by the Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, notes that his sculptural- assemblage work “defies categorization,” as his use of discarded bottle caps and cassava graters “reflects his interest in reuse, transformation, and an intrinsic desire to connect to his continent while transcending the limitations of place. His work can interrogate the history of colonialism and draw connections between consumption, waste, and the environment, but at the core is his unique formal language that distinguishes his practice.” His assemblages, held together with copper wire, “are both luminous and weighty, meticulously fabricated yet malleable. He leaves the installations open and encourages the works to take different forms every time they are installed,” in part because, he has said, “I don’t want to be a dictator. I want to be somebody who suggests things.” As a result, “In morphing to fit various installation spaces, Anatsui’s sculptures, which are often wall-based, challenge long-held views of sculpture as something rigid and insistent and open up his work to exist on its own terms. ‘I work more like a sculptor and a painter put together,’” as he explained himself in an interview that accompanied a solo exhibition at the Sterling and Francine Clark Institute in 2011.

Locally, the Museum of Fine Arts owns Black River (2009), which it describes as a “metallic tapestry” which, when installed, recalls a “topographical map.”

Mary L. Bonauto, lawyer and civil-rights advocate, Doctor of Laws. Attorney Mary L. Bonauto has been a leader in the effort to eliminate discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identify. Long associated with GLAD (Gay & Lesbian Advocates and Defenders), where she has been civil rights project director since 1990, she was lead counsel in the Goodridge case; in its 2003 ruling, the Supreme Judicial Court made Massachusetts the first state to legalize same-sex marriage. She was one of three attorneys who argued Obergefell v. Hodges before the U.S. Supreme Court; the resulting 2015 ruling determined that state bans on same-sex marriage are unconstitutional.

She is a 2014 MacArthur Foundation fellow, and Shikes Fellow in civil liberties and civil rights and lecturer on law at Harvard Law School. At the honorands’ dinner in Annenberg Hall Wednesday night, President Drew Faust called her “one of the civil-rights champions of our time.”

His Excellency Fernando Henrique Cardoso, sociologist and former president of Brazil, Doctor of Laws. Fernando Henrique Cardoso, professor emeritus of sociology and political science at the University of São Paulo, served as president of Brazil from 1995 to 2002—the first incumbent to be re-elected to that office (following a change in the constitution allowing successive terms), reflecting the effect of economic and political reforms he implemented, which ended hyperinflation and rooted out corruption while beginning to address Brazil’s historic inequality and promoting privatization of government-owned enterprises.

The grandson and son of generals, Cardoso sympathized with leftist politics as a student and professor, and fled Brazil following a military coup in 1964, teaching in Chile and Paris. The co-author of Dependency and Development in Latin America, he entered public life as an elected senator in the early 1980s, and became foreign minister (1992) and finance minister (1993-1994) before being elected president.

The conferral of his honorary degree highlights the University’s ties to Brazil. It follows the recent announcement of deepening support—for Brazilian students enrolling at Harvard, and for research on Brazil by University scholars—from long-time supporter Jorge Paulo Lemann ’61, the billionaire banker and investor.

David Brion Davis, historian, Doctor of Laws. In a year when the University formally began recognizing its former deep engagement with American slavery, it seems appropriate to recognize David Brion Davis, Ph.D.’56, widely considered the preeminent historian of slavery and abolition in the New World.

Yale’s Sterling Professor of American History emeritus (equivalent to a University Professorship at Harvard) and director emeritus of the Gilder Lehrman Center—Yale’s center for studies of slavery, resistance, and abolition—he is best known for a sweeping trilogy: The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (1966), which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize; The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (1975), which was awarded the Bancroft Prize, the highest honor in the field of history, and the National Book Award; and The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Emancipation (2014), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for general nonfiction. Challenging the Boundaries of Slavery, published in 2006 by Harvard University Press, traces slavery throughout world history; it originated as the Nathan I. Huggins Lectures at Harvard. He received the National Humanities Medal in 2014, and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences’ Centennial Medal in 2009. Faust referred to his pursuit of history, in his words, as “disciplined moral reflection,” and noted his observation that abolition had been the “greatest landmark of willed moral progress” in human history.

Elaine Fuchs, stem-cell biologist, Doctor of Science. Elaine Fuchs is Lancefield professor at Rockefeller University, where she directs the laboratory of mammalian cell biology and development, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

In nominating Fuchs for the 2015 E.B. Wilson Medal, the highest honor awarded by the American Society for Cell Biology, in recognition of her pioneering exploration of the basic principles of stem-cell biology, Amy Wagers, Forst Family professor of stem cell and regenerative biology at Harvard, wrote that during the past 30 years, she had “performed ground-breaking work that has led a revolution in our understanding of the biology of mammalian skin and revealed broad paradigms that regulate tissue regenerative stem cells across organ systems.”

A 2009 winner of the National Medal of Science, Fuchs is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine, among other affiliations.

Her laboratory website notes of her studies of the epidermis and stem cells that “As basic scientists with an interest in applying our knowledge to human medicine, we chose skin as a model system, because skin epithelium is one of the few tissues of the body whose human and mouse stem cells (keratinocytes) can be maintained and propagated in culture. This feature has been exploited for nearly three decades in the successful treatment of burn patients with epidermis generated from cultured stem cells.”

Her Howard Hughes biography describes the work this way:

To heal from wounds and deal with daily wear and tear, skin constantly regenerates itself. Stem cells are key to this renewal process. Using molecular and genetic approaches in cultured cells and mice, Elaine Fuchs’s work sheds light on how skin stem cells make and repair tissues, and how this process goes awry in genetic diseases, cancers, and proinflammatory disorders.

Fuchs’s team has uncovered many molecules that guide cell divisions in developing skin and control cellular movements during wound repair in adult skin. Some signals turn skin stem cells on, telling them when to make hair and when to repair injuries. Other signals direct stem cells to stop making tissue.…Their research suggests that the behavior of stem cells within tumors is determined by the stem cells’ genetic mutations as well as differences in the tumor’s microenvironment. The combined effects of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors produce hundreds of changes in gene expression in cancer stem cells that are not present in normal skin stem cells. Fuchs’s team wants to study how these changes transform a controlled program of stem cell self-renewal to a chaotic one.

Fuchs’s faculty home page proceeds in a particularly accessible way from the basic facts about the epidermis to the challenging scientific problems and opportunities that arise from working with the skin:

The skin epidermis is what allows us to survive as terrestrial beings. It acts as a saran wrap seal to our body surface, excluding microbes and retaining body fluids. Subjected constantly to mechanical stress, epidermal cells protect themselves by producing an elaborate cytoskeleton that connects to specialized cellular junctions and enables the cells to form adhesive sheets of resilient tissue. The epidermis also produces protective appendages, such as feathers in birds, scales in fishes and hair follicles in mammals. Finally, in order for the epidermis to survive normal wear and tear as well as injuries, it must constantly self-renew, making it one of the body’s reservoirs of stem cells. Given their proximity to the body surface, epidermal cells are also subjected to harmful UV rays, and not surprisingly, epidermal cancers are the most common of all human cancers.

…[W]e are trying to understand how the multipotent stem cells of mammalian skin give rise to the epidermis and hair follicles.…Elucidating the normal process of tissue development is an important first step in understanding how these processes go awry in genetic skin diseases, including cancers.

Arnold Rampersad, biographer, Doctor of Laws. Arnold Rampersad, Ph.D. ’73, now emeritus, was a professor of English at Stanford, where he holds the title of Kimball professor emeritus in the humanities; he also taught at Rutgers, Columbia, and Princeton. A leading scholar of race and American literature, and African-American literature, he has written about W.E.B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. ’95 (the subject of his Harvard doctoral dissertation); edited the Collected Poems of Langston Hughes for the Library of America; and published acclaimed biographies including The Life of Langston Hughes (two volumes, 1986 and 1988), nominated for the Pulitzer Prize, and Ralph Ellison (2007), a National Book Award finalist. He has also written about Arthur Ashe and Jackie Robinson.

A MacArthur Foundation fellow (1991-1996), Rampersad was awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2010. The description of his work accompanying that honor noted the “surprise” that this leading American biographer was born and raised outside the country: “Growing up as a schoolboy in Trinidad, I received an education in literature that some people might dismiss as ‘colonial,’ ” Rampersad recalled. “It nevertheless served me well in dealing with the complexities of American biography.” Of his Du Bois work, he recalled:

I thought that Du Bois was extraordinarily important and complex. My life was changed in a basic way by my first reading of The Souls of Black Folk. And while the historians who had written about him had done good jobs, I believed that they had missed his genuine essence—which is, in my opinion, the grandly poetic imagination he brought to the business of seeing and describing black America and America itself.

He pursued biography, he said, “because I saw the African-American personality as a neglected field despite the prominence of race as a subject in discussions of America. African-American character in all its complexity and sophistication was, and still is, by and large, a denied category in the representation of American social reality.”

His interest in Ellison reflected his own life, Rampersad said, having “come of age just as my native country was marching toward political independence from Great Britain.” In this light, he perceived black American artists as “colonials in their own country, struggling against a greater power for political and cultural independence—relatively speaking—and for freedom of expression.” Reflecting on the changed circumstances of African Americans, he told his interviewer,

[T]he life of the African-American writer has changed dramatically. In part through holding positions at programs in creative writing and departments of English at universities, the black writer has gained a solid presence on the literary scene that has replaced the fugitive nature of expression and publication forced on blacks over the centuries, especially in the slave narratives but continuing into the twentieth century. That presence does not guarantee fine writing but it has led, in my opinion, to an assurance that bodes well for the future. Black literature was described a long time ago as a “literature of necessity” rather than one of leisure. That element of necessity still exists but it does not dominate as it once did. Black American literature as a cultural phenomenon has reached a level of stability and maturity that the circumstances of American life once routinely denied it.

Rampersad, traveling from Stanford, had a big East Coast week: Yale made him an honorary Doctor of Humanities at its graduation on Monday, May 23. Harvard’s graduate school conferred its Centennial Medal on Rampersad in 2013.

The Right Honourable Lord Martin Rees of Ludlow, astrophysicist and cosmologist, Doctor of Science. Martin John Rees, Baron Rees of Ludlow, Astronomer Royal and past president of the Royal Society, is both a leading astrophysicist and an important popular writer on science. His Royal Society biography notes that his theoretical work has ranged from the formation of black holes (the subject of a new initiative at Harvard) to extragalactic radio sources. He is recognized as among the first scientists to predict the uneven distribution of matter in the universe, and proposed tests to determine the clustering of stars and galaxies. He has made valuable contributions to understanding the end of the so-called “cosmic dark ages,” after the Big Bang, when the universe was “as yet without light sources”—before the first stars formed.

Lord Rees served as master of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 2004 to 2012; as an undergraduate, he had studied mathematics there. He remains a fellow of Trinity College and emeritus professor of cosmology and astrophysics at Cambridge.

Judith J. Thomson, moral philosopher and metaphysician, Doctor of Laws. Judith Thomson, professor emerita in MIT’s department of linguistics and philosophy, where she was Rockefeller professor of philosophy. She has pursued studies in ethics and metaphysics, and critiqued utilitarianism. Her book The Realm of Rights (Harvard, 1990) probed the meaning of the concept of a right as the basis for a systematic theory of human and social rights. She is known for employing “thought experiments” to tease out philosophical points; one of these underpins her 1971 essay, “A Defense of Abortion,” which examines a pregnant woman’s right to control her own body (as opposed to focusing on the status of a fetus). In the thought experiment, she imagines an adult woman captured and tied into the circulatory system of a famous artist suffering a kidney ailment—for nine months. The constraints imposed to save the artist’s life raise issues about the autonomy of the woman and her right to control her body—and the resulting conflicts. The essay understandably has been widely discussed among moral philosophers and bioethicists.

Thomson has also probed such challenging issues as assisted suicide and preferential hiring. Many of her important essays appear in Rights, Restitution, and Risk: Essays in Moral Theory (Harvard, 1986).

Steven Spielberg, filmmaker, Doctor of Arts. Steven Spielberg has directed, written, and produced movies ranging from the historically serious and shattering Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan to massively popular entertainments such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Jurassic Park, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Jaws. Harvard’s news office indulged in a bit of fun, teasing the announcement of his role as afternoon speaker at Commencement by releasing a video trailer using University venues and familiar audio clips from the movies.