Imagine running the Boston Marathon in 1635, a few years after the city was founded. Your route would have traveled through forests filled with moose, wolves, and beavers, ending in a swim through the swampy waters to the west of the Boston Neck—then a rail-thin strip of land connecting the city to what is now Roxbury and Dorchester. The city’s boundaries were announced by gallows and a wall, marking a dramatic shift from native North America to an outpost of the expanding British empire. Near the finish line, if you looked to the right during your swim, tall hills would have risen from the water. Cattle would have meandered through the grass, grazing in the newly established Boston Common.

Much has changed since then, as shown in an exhibition of maps, “Building Boston, Shaping Shorelines,” on display from the Harvard Map Collection through late April in the Pusey Library Gallery. This collection reveals Boston’s transformation from a home to the Massachusett people, to a colonizer’s fortress, to the city we know today. Those transformations are written into the land itself: Boston has physically spread from a hilly peninsula to a wide expanse of land, like a heap of wet batter slowly smearing out into a flat pancake. Beacon Hill was once around 60 feet taller than it is today, while other hills have been removed entirely, shoveled into the swamp to lift Back Bay out of the water in the nineteenth century. The Boston Neck has widened into an extension of the mainland. As Boston prepares for twenty-first-century sea-level rise, current inhabitants may regret the triumph of those early engineers.

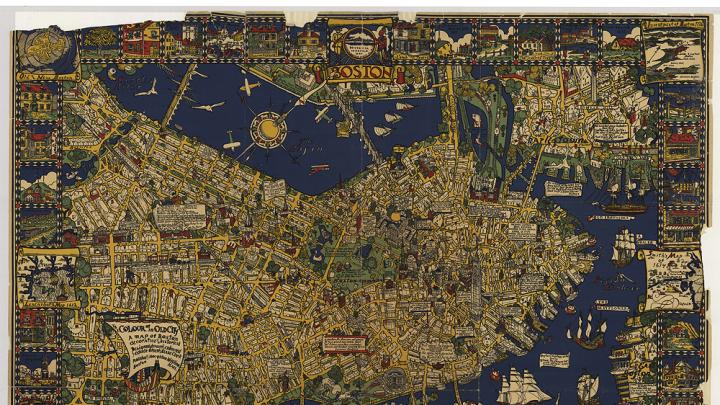

The maps in the collection span a wide stylistic range: some are spectacular artistic achievements; others are about as charismatic as an Excel spreadsheet. My favorite is Edwin Olsen and Blake Clark’s 1926 “The Colour of an Old City: A Map of Boston, Decorative and Historical.” Their ocean is a rich blue, and the buildings of the city are spectacularly detailed and caricatured. Exaggerated landmarks burst from the yellow streets and are announced with all-caps labels. Olsen and Clark overlay the map with panels of poetry and history, creating an intricate and beautiful portrait of the city.

But maps are always political, no matter whether they aspire to be art or objective records of fact (think, for example, about how cartographers today handle Taiwan). Perhaps the most interesting parts of the exhibit are the stories that these maps leave out, or push to the margins—omissions carefully documented by the curators. Though Olsen and Clark’s map does address Native Americans, it leaves out the violence of their displacement and the persistence of indigenous people in New England. In reality, the Massachusett people are still here, speaking their language in the Greater Boston area, but they do not show up on any of these maps. Their conquest, too, is hidden away, both by Olsen and Clark and by other cartographers: to the creators of these maps, expansion seems natural or even destined.

Later maps bear witness to other kinds of injustices, but the damage becomes apparent only if you look closely. A set of insurance maps gives an actuary’s view of primordial gentrification in the postwar decades: the city tore down buildings with low property values to build public housing, only to turn around and deny most of the old residents an opportunity to move into the new buildings (which were de facto segregated until 1988).

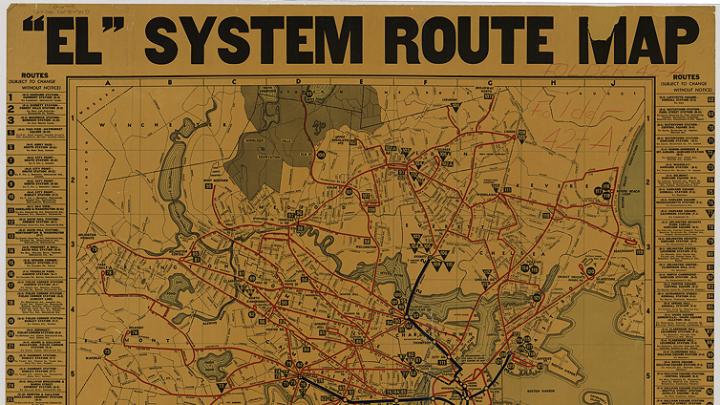

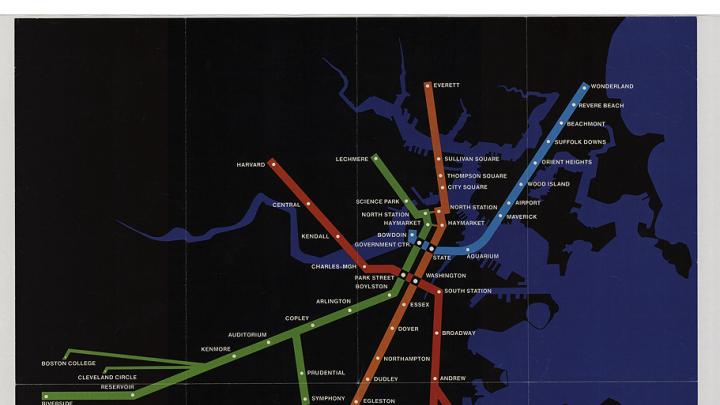

Of course, there is much more to this exhibit than the indirect documentation of historical disasters—Boston’s past is full of triumphant moments, too. Even though they are informational and restrained, the maps depicting the growth of the MBTA seem to burst with civic pride. The exhibit illustrates how Boston’s elevated rail system, the “El,” evolved into an expanding network of T trains and bus routes.

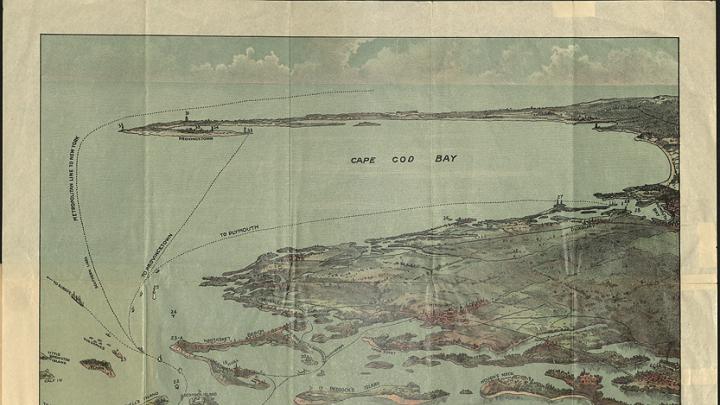

Much of the exhibit shows views of Boston Harbor, some expanding all the way to Provincetown. The early maps focus on the sea, diagramming how and where British Navy vessels could safely anchor. As time goes on, the focus of many maps changes to center on Boston itself, looking eastward to show the Cape on the horizon. If the exhibition conveys one lesson, it is that Boston has never stayed still: not the people, not their perspectives, not even the land.