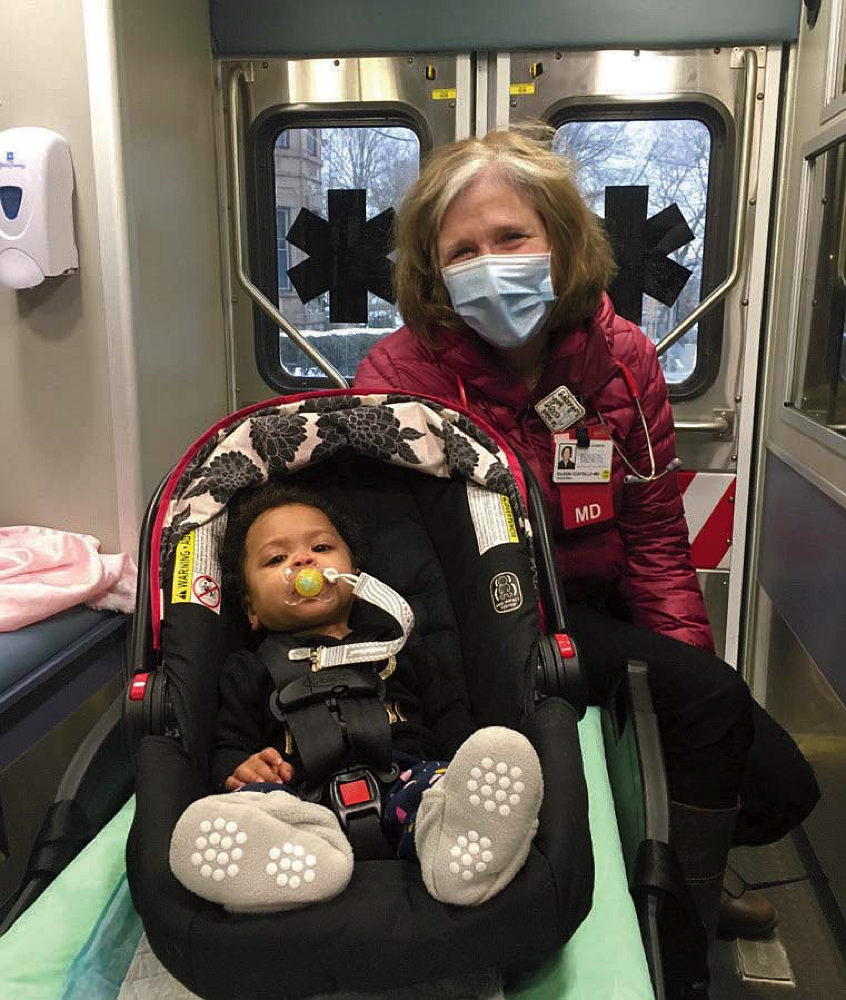

The ambulance rolls onto a treeless street in Boston, stopping at a triple-decker across from a defunct bar and an asphalt lot. The medical team greets Crystal, exiting the house with her son in a baby carrier, and helps them inside the tight, cozy space. It’s Jasiah’s four-month exam, and because Crystal has missed several appointments, physician Eileen Costello ’80, chief of ambulatory pediatrics at Boston Medical Center (BMC), has come to her. Crystal is part of SOFAR (Supporting Our Families through Addiction and Recovery), a multidisciplinary treatment program Costello and her team created in 2017 to pick up where intensive ob-gyn care ends. “For the vast majority of our moms,” she says, “getting pregnant was a catalyst for recovery, so when we meet them, most are in their first year, which is an extremely high-risk time for relapse.”

Costello knows that Crystal previously lost custody of two older children, but that now, at age 30, she counts four years free of opioid addiction, and is determined to raise Jasiah herself. Living in an apartment shelter with three other moms and their children, she takes her clean life a day at a time.

One reason she missed her appointments, Costello learns, is that her older brother, despite a year of sobriety, died of an overdose two weeks earlier. Crystal relays the story—how their father, 13 years clean himself and the legal guardian of his son’s three small children, was coping. How he chose to cremate her brother, who took a bad fall when he shot up “and his face was messed up, so he didn’t want to scar the children by them seeing their dad that way.”

“It’s just been rough,” Crystal admits.

Costello looks pained. “I’m so sorry.” She and the nurse are right there, listening, while unzipping Jasiah from his snuggly. “Hi, angel boy,” Costello goo-goos at the baby. “He is looking awesome, Crystal! Look at his eyes, so bright and beautiful! Yes, yes!” She examines the gurgling, smiling boy who has inherited his mother’s heart-shaped face.

She asks about Crystal’s living situation, her cravings and anxiety, her grief. How is Jasiah eating and sleeping? “He’s a little chunky monkey, which is good,” she says, noting that he’s already teething. Costello also wonders, “What about your dosages?” Crystal is trying to reduce her daily methadone, but Costello discourages decreasing too fast: “You don’t want to feel terrible. And six to 12 months postpartum is a really high-risk time for relapse. If you’re feeling good and not having cravings—”

“I want to keep it that way.”

“—take your time. A lot of that urge to ‘Get off, get off’ is because of the stigma of treatment.” Costello stops examining Jasiah, looks at Crystal, and says emphatically: “If you’re still on it in five years, that’s okay with me. As long as you’re strong in your recovery and mothering your baby, that’s the most important thing.”

The mobile unit was established in April 2020 to help keep children current on vaccines against rubella, tetanus, and other common childhood diseases, after pandemic restrictions halted routine visits to BMC’s outpatient units. “Suddenly only 10 percent of our families were coming in,” Costello reports. “I was worried that in another year we’d have a huge cohort of unvaccinated kids in the city, with whooping cough and measles, which are especially contagious, and that would be very dangerous.” The unit—essentially a house call on wheels—has been hugely successful. More children have been vaccinated, including against flu, than in the previous year. The ambulance also supports the Medical Center’s Project REACH, a COVID-19 response that helps supply isolated families with diapers, wipes, clothing, toys, and food.

BMC was founded as Boston City Hospital in 1864 (the first municipal hospital in the United States) and has long focused its mission on health equity through pioneering programs like Project RESPECT (Recovery, Empowerment, Social Services, Prenatal Care, Education, Community and Treatment), which covers ob-gyn and neonatal care for recovering mothers before SOFAR takes over. For Costello, joining BMC in 2016 meant overseeing primary care for 14,000 of the neediest children across the city.

“We see kids from newborns through their early 20s,” she reports, “and about 90 percent of our population is on public insurance.” They struggle with the range of poverty-related challenges: paying for medicines and utility bills, finding transportation and quality housing. “The other day,” she says, “I saw a baby who had been bitten by a mouse in her crib.” Every child visit includes questions for caregivers, she adds, like “‘Is there a time when you cannot put food on the table?’ I probably write more prescriptions for the hospital’s food pantry than I do for amoxicillin.”

In addition to about 235 SOFAR patients, Costello treats children with developmental delays or spectrum disorders. That expertise grew naturally after her oldest son was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder in 1991, as the phenomenon was gaining wider recognition and study. She was working at a Dorchester neighborhood clinic then, seeing developmentally atypical children and hearing about sensory integration, weighted vests, and different therapies from their parents at the same time she was learning how to care for her own son. She ultimately completed a mini-fellowship in developmental and behavioral pediatrics at BMC, and co-authored the pioneering 2003 book Quirky Kids: Understanding and Supporting Your Child with Developmental Differences, with NYU professor of journalism and pediatrics Perri Klass ’78, M.D. ’86. (They became friends during residency at Boston Children’s Hospital.)

She says the updated edition of Quirky Kids, which appeared in February, speaks to the desperation of so many parents who have spent the pandemic home alone with challenging children “when the routines and structure critical to everyone—but especially those on the spectrum—was so thoroughly disrupted,” and the outside support network of doctors, therapists, day care, and schools disappeared. By now, Costello’s been treating kids on the spectrum for two decades and “because I’m interested, talk the language, and walk the walk, parents would refer each other to me.”

That closeness to her patient families has always prevailed. After Dorchester, she joined the Southern Jamaica Plain Health Center, around the corner from where she and her then-husband Matthew Gillman ’76 (they are now amicably divorced) were raising their three boys and a foster daughter. She’d also see these families at the grocery store and Little League games, and still enjoys running into former patients around the neighborhood.

Now, she rides the subway to BMC. Walking into the bustling lobby, she feels like “these are my people. This is where I belong—this is the reason I went to medical school.” She traces this affinity partly to growing up within an extended family in Hyde Park, a solid working-class corner of Boston. Her father and two brothers were firefighters, and everyone was linked to city government and politics. In fact, her outspokenness on her public high-school’s biracial student committee, formed to help smooth the transition to controversial court-mandated school integration through busing, inadvertently got her to Harvard. The confrontation began in 1974, at the start of her senior year when “there was just so much hatred that I started getting threats, and my parents were afraid for me.” They scrambled to find another school, and she ended up on scholarship at Thayer Academy, in Braintree. There, a guidance counselor “saw things in me that I didn’t see myself,” and pushed her to apply to Harvard.

Harvard “loves stories like me,” she says: a student of modest means gets a golden education ticket. “But it really did change the course of my life. I had a ball.” She made “a lifetime of friends” and her work-study jobs included assignments as a research assistant for Jerome Kagan, now Starch research professor of psychology emeritus, and at Massachusetts Mental Health Center, under psychiatrist, psychologist, and behavioral economist George W. Ainslie, M.D. ’69. Concentrating in psychology and social relations, she completed pre-med requirements mostly in summer school. After graduating, she spent a year in Taiwan as a Luce Scholar, affiliated with Veterans’ General Hospital in Taipei. Once back in Boston, while applying to medical schools, she also explored (and rejected) a possible career in teaching. “You have to have the capacity to be in a room all day with, you know, 25 12-year-olds who want to torture you,” she says, laughing. “It’s so much harder than being a pediatrician!”

Save for that fellowship and medical school at Northwestern, she’s never lived or worked outside the city: “I’m such a Boston girl, no doubt about it.”

Devotion to her work also springs from her own family’s experience with addiction. Costello tells all her “SOFAR moms” about her own father’s efforts to stop drinking at age 50, through Alcoholics Anonymous. Even after years of sobriety, he still attended meetings, she recalls. “My mom used to say, ‘Jimmy, why are you still going?’ and he said, ‘I just need to keep hearing the message.’” Time spent there, with his community, was time he used to spend drinking, and “he sponsored other people, helped them, and we didn’t even know all of that until his funeral and all these people came out.” His nascent recovery, during her teenage years, was transformational for the entire family: “That’s why I believe in recovery. I believe people can do it.”

Photograph by Nell Porter Brown/Harvard Magazine

But they need built-in support structures. Most opioid-crisis funding and research for children, she says, has centered on the prenatal and neonatal periods. But after studying patient records, Costello realized that these mothers’ connection to that multidimensional medical care faltered not long after they and their babies left the hospital. Now SOFAR, part of BMC’s pediatric primary-care clinic, kicks in at that juncture, and follows kids through young adulthood. The program’s first two years were funded by grants ($50,000 and $35,000, respectively) from the pediatric department’s Center for the Urban Child and Healthy Family, but now SOFAR relies on donations and money raised by its seven-member team (including two general pediatricians and a developmental and behavioral specialist). Costello, a yoga enthusiast, annually completes the 25-mile Rodman Ride for Kids, generating about $10,000.

SOFAR mothers and parents learning to develop the insight, patience, and maturity to care for difficult children on the spectrum face similar struggles, although recovery in itself is a far more precarious venture. Becoming sober is like experiencing a rebirth, Costello says: many of the mothers she knows have lived under bridges, in parks, in cardboard boxes. “I have patients in long-term recovery and they say, ‘I can’t believe that used to be me.’” But as recovering new moms, they are also entering a new world, a sober world, at the same time as their infants (who may need treatment for symptoms of opioid withdrawal). Their burgeoning new identities as sober women and mothers converge, Costello says, and “both are a full-time job.”

Moreover, some 80 percent of SOFAR mothers have dual diagnoses: mental-health and substance-abuse disorders. And almost all have intergenerational dual-diagnoses within their immediate families. Costello, who thought about specializing in psychiatry before choosing pediatrics, considers mental health as important as physical health, if not more so, and asks: “Did they start using drugs to medicate a mental illness, or did the lifestyle they were living while they were using predispose them to mental illness and trauma? Do they have PTSD because of what has happened to them as a result of using drugs and living that high-risk lifestyle?”

Something in the vulnerability and resilience of these women draws Costello in. “And you really have to work hard to gain their trust, and for them to believe that you actually care about them and their babies, and you’re not just trying to take their babies away, which I think the rest of the world is, right?” she says. “There’s so much judgment. And they love their babies as much as anyone else.”

Even so, she knows that individuals in recovery are an extremely challenging population to treat. “Addiction is a chronic disease of the brain,” she says, “and lapses are almost expected as part of recovery.” BMC attracts dedicated, mission-inspired practitioners—“People are here because they want to be here,” she says, “because if you didn’t want to be here, the work is just too hard.” And sometimes, that hard work and passion aren’t enough. The cases, the human suffering, the fates of children, are wrenching. “We get so connected to the kids and moms, obviously,” she adds. “And if the mother relapses and the kid is totally traumatized—all of us have broken down in tears about it.”

Everyone supports the need to step away, and to remember “that no one can do this kind of work forever,” she continues, then pauses. “But, you know, one of the joys of being a pediatrician is knowing that kids are pretty resilient and they’re very responsive to the right kinds of interventions. And that’s what everyone here is working toward: trying to create a better future for the kids we see, trying to make sure they don’t become the next generation in their families with substance-abuse disorders. So, I think you have, we have, that kind of power to help kids and families develop coping skills other than picking up.”

At the end of the ambulance exam, as Jasiah is packed back into the baby carrier, Costello tells Crystal how glad she is to have seen them both in person. “I’m incredibly sorry to hear about your brother. You’ve had unspeakable traumas in your life, my dear. I mean, unspeakable. It’s really nothing short of a miracle that you’re sitting here talking to us, clean.”

“Yeah,” Crystal nods, “when I was pregnant with him, I went through some awful domestic violence. There were days when I didn’t think we were going to make it, you know? But he’s in jail now.”

“And you have a gorgeous son.”

“I’ve come a long way, man.”

“Yes, you have. You’ve already hit bottom—10 times.”

“It can only go up.”

“Yes. Good.”

“That’s what I say. Every day, even if it’s a bad day. I say, ‘Tomorrow will be better.’”

It’s close to Jasiah’s nap time, and after a hug from Costello, Crystal goes back inside the triple-decker. The medical team re-boards the ambulance and readies for the next visit, to see a seven-month-old girl and her young mom, who relapsed two weeks earlier. “She was not with the baby when she used, and she called and let everybody know this happened and she felt terrible about it,” Costello explains before the visit. “The fact that she was so open and so contrite. And so like, ‘This is not who I want to be. I don’t want to be doing this’…is to us a very positive prognostic sign.” But Costello is worried.The mother is fragile, on edge. “Those are the people,” she says, “we want to keep closest to us.”