Tony Saich begins his magisterial account of the hundred-year history of the Chinese Communist Party (with publication timed for the centennial, this July) with a conundrum. The CCP today has almost 90 million members. With branches in more than 4.5 million grass-roots organizations, including companies, universities, hospitals, high-tech parks, and neighborhood committees, the party is thoroughly embedded in Chinese society. So, too, is it inseparably intertwined with the Chinese government, from the highest echelons of the nation’s political leadership down to the lowest levels of local bureaucracy. But, as Saich, Daewoo professor of international affairs, quite rightly acknowledges: “The party’s longevity, size, endurance, and ability to overcome seemingly impossible odds make it a very distinct political organization. Yet, it is difficult to define precisely what the CCP is.”

Should we understand the CCP most fundamentally as a sui generis mode of social control, surveillance, and ideological indoctrination: the modern-day, Sinecized apotheosis of Leninist-style political organization? Or, is the party something more like what in most societies we would term the “establishment,” a loose network of elites from across diverse spheres of social life—business, education, the arts, the military, politics, etc.—who share little in common except social status, influence, and vague loyalty to the hierarchies of the status quo? From yet another tack, should the party be seen more abstractly as an institutional legacy and moral extension of the nation’s founding: something (perhaps akin to the U.S. Constitution) that can’t be challenged in terms of its intrinsic legitimacy, but that can be repurposed, updated, and reconfigured to meet the evolving interests and aspirations of society at large or particular constituencies within it?

While From Rebel to Ruler provides space for all of these interpretations, none gets to the heart of what this book is about. For Saich, the answer to the question of what the party is, or at least what about the party really counts most, is the organization’s senior-most leaders, their political visions, and the policies pursued to realize those visions. Rich in empirical depth and vast in coverage, the book is in many ways a traditional political history, one that focuses on the major leaders (Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, etc.) and major events (the Long March, the Great Leap Forward, Cultural Revolution, Reform and Opening, etc.) of the past hundred years. In this sense, it is not unlike a traditional political history of the United States organized around presidential administrations, nationwide elections, and momentous policy shifts.

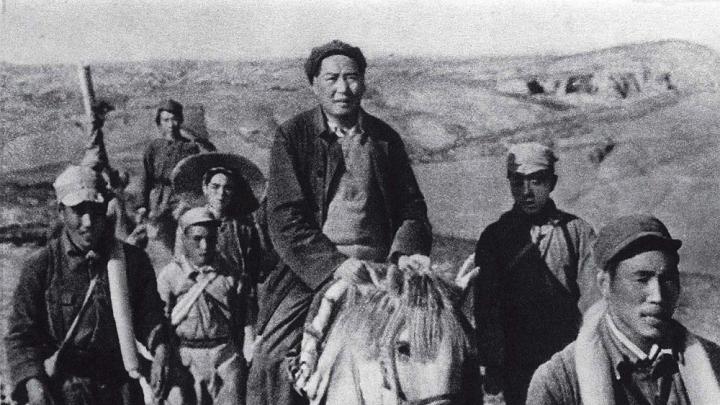

Peasants on a communal farm in the 1950s, during the Party’s disastrous “Great Leap Forward” campaign

Photograph by Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

In this case, though, what an extraordinary account of elite politics Saich has to tell. On the basis of a host of primary sources and his own crystal-clear analysis, he identifies themes extending from the genesis of the CCP in the early 1920s all the way through the rule of Xi Jinping over a rising global superpower today. Immediately striking among these themes is the omnipresence of struggle: struggle against the foreign-controlled police and local warlords in the 1920s who were determined to root out subversive leftist political activity; struggle against the rival Nationalist Party (KMT) for revolutionary and national leadership; struggle within the party among various elite factions, especially early on pitting those more closely linked to the Soviet-controlled Comintern against those, like Mao, whose ideas and experiences were more home-grown; continued struggle within the party under Mao’s leadership after the official establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949; and struggle against all manner of foreign threats, including a cataclysmic rift with the Soviet Union in the 1950s and ’60s, and a deepening conflict with the United States today.

With struggle has come the additional theme of profound sacrifice and bloodshed: near total annihilation in the face of the KMT’s 1927 “White Terror”; near total annihilation yet again at the hands of the KMT during the Long March retreat of 1934-35; ghastly battlefield losses in the Anti-Japanese War (World War II) and the War to Resist America and Aid Korea (Korean War); millions of deaths stemming from the famine induced by the Great Leap Forward, a grievous error by the party itself; and at least another million lost through the internecine violence of the Cultural Revolution, yet another grave leadership error.

But, struggle and sacrifice have generated still another theme, the party’s almost mythic capacity for resilience, endurance, and re-creation. At so many points during its century-long existence, the CCP appeared to be in its death throes, whether as a result of external attack or self-inflicted internal strife. Yet it has not only survived, but has led China to a level of worldwide power and influence that just a few years ago, let alone a century ago at the party’s inception, would have been unimaginable.

What do these historical patterns and legacies mean for governance in China now? At least two points underscored by Saich stand out.

First, despite dizzying ideological zigzags over time, and equally head-spinning volte-face with respect to policy practice, China’s political leadership today still goes to extraordinary lengths to insist on its own infallibility and inevitability. As Saich beautifully documents, whenever the party has undergone major internal power struggles—Yan’an in the early 1940s, the post-Mao shift to opening and reform in the early 1980s, and the rise of Xi Jinping in the context of a massive anti-corruption campaign more recently—no effort has been spared to totally rewrite history, erase inconvenient truths from the past, and thoroughly massage the facts so as to justify both the historical inevitability and moral rectitude of the leadership cadre that emerged. Saich writes:

The party believes that it possesses the ability not only to correctly interpret the past but also to outline the future, and this belief has led the party to declare its infallibility. Thus, when mistakes are made, blame must lie either with members of the party following the incorrect political line and leading party members astray, or with “outsiders,” especially foreigners, meddling in party affairs.

It comes as no surprise today, therefore, that although China’s leaders are at times tolerant of a modicum of debate within mainstream society, they brook no real dissent, and often seem to perceive threats from almost every corner imaginable. That said, it is somewhat vertigo-inducing that in its continuing effort to manage the historical narrative, the CCP’s present leadership posits a line of legitimacy and greatness extending from Xi Jinping not just through Mao Zedong, the ostensible father of the Chinese revolution, but all the way back to Confucius and Chinese high antiquity—the very targets of the Chinese Revolution itself!

That leads to a second point raised by Saich. For all the fragility of China’s governance model, and for all its costly blunders past and present, the CCP enjoys a relatively high degree of legitimacy among Chinese citizens. Saich conveys the point in all its nuance and complexity. He writes on the one hand that “For many, the [communist] revolution was experienced as the replacement of ‘one form of domination with another,’ rather than any form of personal liberation.” But on the other hand, he continues, “Despite the daily demonstrations, today there is little pressure from below to push the CCP to undertake significant changes, and satisfaction levels remain high. Unlike in the Soviet Union, the reforms have created a substantial group of people who are invested in the current system.”

Indeed, in a way that undoubtedly resonates with many Chinese citizens today, Saich reflects on his own experiences in China by saying, “Forty-five years ago, when I was a student in the country, I could not have imagined the changes that China has experienced. If anyone had dared to suggest that it would be possible to pull China out of the morass of the Cultural Revolution, I would have told them that the idea was crazy.”

The party is inextricably associated with a revolution and modernization process that many Chinese still see as their own, something linked to their personal identity. Even more profoundly, the party is linked today to the attainment of a level of national economic, technological, and military prowess that many citizens understandably view as a kind of dream (as it would be in any society enjoying such an achievement).

That is not to say that the brutal suppression of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, the squashing of civic rights in Hong Kong, and any number of other abominations exacted by the Chinese party-state should be condoned or overlooked. Rather, it is simply to say that the party has managed to associate itself with a set of realized aspirations that resonate with much of the Chinese public: urban living standards on par with the advanced industrial West, state-of-the-art technologies omnipresent in daily life, a national space program at the cutting edge of science and engineering, and the effective management of a pandemic that has hobbled almost every other society across the world. Alas, in the eyes of many Chinese citizens right now, CCP-style authoritarianism looks pretty appealing relative to what the world’s leading democracies, especially the United States, have on offer.

That still leaves open the question, though, of what the party fundamentally is. The answers matter.

Xi Jinping certainly seems to be bending over backward to assert that the Leninist ideal represents present-day reality. How else can one read in his oft-repeated admonitions that “East, West, South, North, and central, the party leads in everything,” that “maintenance of the party center’s authority at all times and under all conditions is non-negotiable,” and that all party members must “firmly remember their mission, and on their own initiative protect the party’s centralized authority and leadership.” The U.S. government, in turn, in its recent characterizations of the threat posed by China as “whole of state” and “whole of society” in nature, and by explicitly calling out the Chinese Communist Party as the epicenter and originator of that threat, echoes Xi’s Leninist formulation. The none-too-subtle implication is that the United States and the People’s Republic are now locked in an existential struggle between societies so vastly different that they can barely recognize each other—let alone cooperate or maintain any semblance of trust.

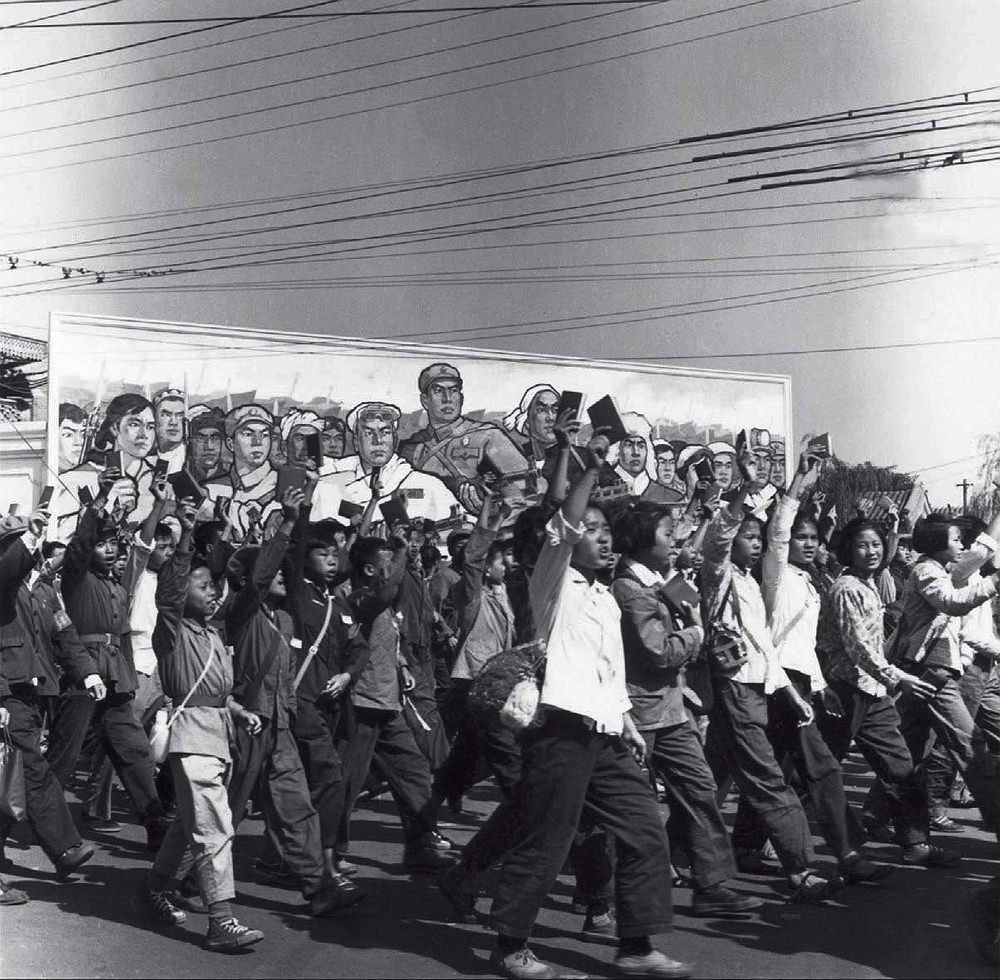

High-school and university students, mobilized as Red Guards, wave Chairman Mao’s “Little Red Book” at the inception of the traumatic Cultural Revolution; intended to overthrow party leaders who had deviated from the leader’s ideology, the movement convulsed the entire society, setting the stage for a period of reforms, and, today, continuing efforts to maintain the CCP’s primacy.

Photograph by Jean Vincent/AFP via Getty Images

But there is an alternative view that carries its own set of implications and possibilities. In this interpretation, the CCP is as much interpenetrated by society as vice versa. Further, the party encompasses individuals who bear neither loyalty to the organization nor any belief in Communist ideology; most party members are societal elites and social climbers who have nothing to do with the state; and the state itself (including its senior leadership, potent security apparatus, and vast bureaucratic agencies) behaves the way it does not because it is communist or linked to a distinctive communist party, but instead because it is authoritarian and it has evolved to that condition from a distinct set of historical circumstances—exactly those described in From Rebel to Ruler.

All this suggests, perhaps, a system far less internally coherent and far more fluid than its leaders (and many of its geopolitical adversaries) are willing to acknowledge. Importantly, that in turn suggests profound skepticism on all our parts when confronted by the daily back-and-forth of bombastically sanctimonious and hubristic propaganda emanating from Beijing, and hyperbolic threat-mongering and demonization (some of which veers into outright racialization and racism), emanating from Washington.

While questions about what China is and is becoming will continue to perplex, readers searching for a road map toward sound answers would be well advised to begin with From Rebel to Ruler. A better primer on Chinese elite politics and political history cannot be found.