An Essay on Eric

Eric Hegsted ’73 lived in Yukon Territory for four decades, until his death in a snowmobile accident in 2019. Though urged to write publishable essays on his experiences there, he wanted to avoid the temptation of tinkering with his life for the sake of narrative interest. This essay, “Blazing,” is the exception.

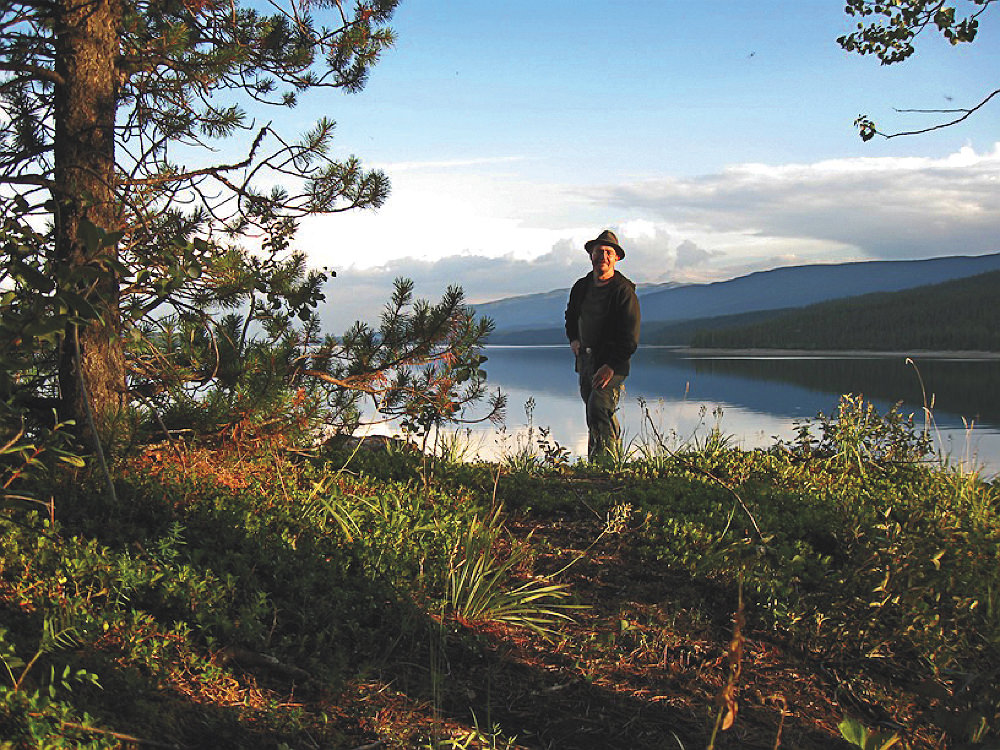

Eric moved to Yukon Territory in 1978 after marrying Anne Macaire, who had been living there for many years. He soon decided that choosing the Yukon as his home entailed fully embracing a life in the wilderness. This included acquiring a trapline: a quarter-million acres of wilderness that Eric had the sole right to trap on and steward. Eric and Anne lived on Tillei Lake, which could be accessed only by plane, for three winters in a log cabin they built. After their first son, Charles, was born, they moved south to the east arm of Frances Lake, which could be reached by boat, where they raised Charles and Will, their second son, for about 10 years. The overland trail between Tillei and Frances is the setting of “Blazing.”

To provide their growing children with a social world, Eric and Anne moved the family to Whitehorse, the capital of Yukon, Eric taking a government job. Upon retiring, now in his sixties, he left the Yukon briefly to become a student again, studying music composition at Vancouver Community College, after which he returned to Frances Lake, dividing his time between the family cabin there and Whitehorse, where Anne continued to make her home. For the last seven years of his life, Eric lived quietly and contentedly in nature.

But he was never out of contact with civilization. Wherever Eric lived, even by himself in the wilderness, he conjured into a center for music: jazz, classical, folk, blues, and country. At various eras of his musical life, he mastered the mandolin, bongos, and alto saxophone; throughout it, he played the guitar, for which, typically, he invented his own tuning. Eric installed a solar-powered satellite dish on his wilderness cabin. On a journey with his sled dogs, he used his new Walkman to listen to the Haydn “Lark” quartet.

And he always stayed in electronic touch with Dick Connette, his roommate at Harvard beginning freshman year, and John Limon, who became their (at first) unofficial roommate once Eric removed the fire door between their room in Hollis and John’s for unimpeded visiting. The first musical collaboration of Eric, a Classics concentrator, and Dick (after graduating, a New York City composer) was the score they wrote and performed, on guitar and celesta, for a Euripides tragedy at the Loeb. Their mutual artistic stimulation lasted half a century until Eric’s death. With John, an English professor at Williams College, he exchanged email opinions about books. When John needed to know, for a study, if The Count of Monte Cristo was worth reading, Eric was ambivalent; but he located a Classic Comics version online, which arrived in John’s mailbox two days before the accident.

But return to college life, freshman year, for a coda. Dick, Eric, and some friends decide to risk walking on a frozen lake in Lands End, Rockport. The ice breaks into floes; all except Eric retreat safely to shore. Eric’s floe drifts away. Dick grabs a tree branch, hops on a convenient floe, and pushes himself out to rescue his roommate. He comes upon Eric calmly smoking a pipe. They discuss which floe to take back. Eric says that he’s become fond of the one he’s on, Dick joins him, and they pole themselves safely to land.

—Anne Macaire, Dick Connette, and John Limon

* * * * *

Blazing

Learning the Way from the Wilderness

by Eric Hegsted

Before I came to the Yukon I thought I knew about blazing a trail. I had often heard the phrase used metaphorically for innovative leaders in science or the arts, applied to Copernicus or Schoenberg. For the actual process, I might have imagined a frontier scout in fringed buckskins peering ahead into a dark forest, holding aloft a flaming torch which illuminates, in the background, the fearful yet trusting faces of his pioneer followers. It was not until I consulted the scholars of my collegiate dictionary many years later that I learned that there are two words “blaze,” related but different: one is an intensely burning fire; the other a white mark on the face of an animal, or one made on a tree by chipping off a piece of bark.

The second year on the trapline Annie and I started cutting a trail that wound from the south end of Tillei Lake, through the dense woods, past our wall tent overlooking a small pond, then up to the saddle between two unnamed hills and across the meadows before descending to a place where we could cross the river safely below the dangerous canyon. In the snow it was no problem to follow the trail packed by our snowshoes, the dogs and the toboggan, but we needed to save the exact route for next year so that the weeks of work spent clearing the path with axe, saw, and clippers would not be wasted. But it seemed too crude to mark the trail by hacking at the trees along the way, and in our gear flown in with the Otter in the fall we had brought a dozen rolls of plastic surveyor’s tape in the most unnatural color we could find, a bright acid green. The last trip back in March we flagged the trail at every twist, our hands numb from taking off our mitts to tear off lengths of tape and knot them to the branches of the spruces and willows. It hardly seemed necessary as the route was so obvious.

Early the next November we headed out on snowshoes from the Fish Camp to break out the trail again. The first section, to the tent, we had been over many times and found fairly easily, but more by remembering landmarks like the leaning spruce where the trail headed up a slope or the big pine that marked the beginning of a long straight stretch. For there was new deadfall and the undergrowth was now not flattened under four feet of snow. Even one summer’s midnight sun had bleached the tape and the fall’s early snows covered the branches and bent all the willows in new directions. Now, the acid green of the trail tape was somehow exactly the same color as that of the afterimage that appeared when you closed your eyes on a sunny winter day, and if you missed even one flag and headed off on the wrong tree, or even the wrong side of the right tree, you ended up in unfamiliar places. After hours spent trying to locate the elusive flags, we gave up. That year I blazed the trail.

You may imagine a woodsman moving swiftly through the forest, barely breaking stride to swing his axe and mark the trees with deft blazes. But as a novice axeman I found it was hard work, especially as my blazing was done in late winter, when the trees were freighted with the whole season’s weight of snow. Here is the method I learned:

Approach the tree and gently trim away any branches that might impede your swing or obscure the blaze. Then strike the trunk with the poll of the axe several sharp blows. Immediately brace yourself: the snow above may only sift down, but it may fall in an enveloping torrent with the loads of large branches coming down like bags of cement and landing with a resounding whump.

You want a deep hood on your parka and will find that holding your hands up in an attitude of prayer or stagey surprise will keep the snow from filling up the cuffs of your mitts. If you wear glasses, keep your head down. Start cutting now but be ready for more snow to fall at any moment.

In a stand of slender pines it is easy to make perfect lens-shaped blazes, “no larger than a silver dollar” as recommended by John Rowlands in his lovely book, Cache Lake Country, but on large spruce with thick bark it takes several strokes to cut through to the sapwood. Fresh white blazes are visible at quite a distance and very often the sap from a pine or spruce will flow over its wound and make a smooth yellow varnish that will keep the blaze visible as long as the tree stands. On a dead tree a new blaze will stand out well but the wood will weather to grey in a couple of years and will make little contrast with the bark. Poplar bark is soft and easily cut—it will show for years where a black bear scrambled up the tree—but without the rosin of the conifers, exposed wood will soon turn grey. The worst place to mark a trail is through an old burn, where the blazes darken to the same color as the burnt trunks and you have to see the cuts of the axe to confirm the mark. The marked trees themselves are likely to fall over as their roots decay.

A blaze that is too large is unsightly and it insults the intelligence of a person following the trail to mark every tree when they are close together, but it is nice to be able to see two blazes ahead. Some people cut the right side of the trail with single and the left with double blazes and use special marks to indicate forks, the location of traps or other information, but I have rarely bothered with that. However, when we moved to Frances Lake and I needed to follow the trail to Tillei from the other direction I understood to my chagrin the reason for marking trees on both the front and the back.

Limbing the lower part of the tree on the side facing the trail helps mark the route and many of the old trails around here are mainly indicated with small trees marked this way. A long prominent blaze or a “lopstick,” a tree with the branches oddly trimmed, is good to help locate the trail at the edge of a clearing or pond. A stout pole works even better than an axe for limbing when the branches are brittle on a cold day, or even a backhanded swipe with the frame of a Swede saw. This is the simplest and lightest tool for all-around trail clearing, but long-handled pruning clippers are the best for willows and alders. To me, a blaze cut with a chainsaw looks utterly vulgar, but I am very happy to use one on heavy deadfall.

Over Frances Lake, 2017

On too many trails the blazing has been done too soon. The route usually needs to be scouted several times before it can be set. It is aggravating to discover that there is a better or more direct route for the trail after the blazes have been cut. Then you have the choice of following the old path or blazing the new one and leaving a permanent, confusing record of the earlier mistake. Also, many trails are begun well, with blazes on nearly every tree in an easy section then fewer and finally none as the going gets more uncertain. As Nessmuk wrote in Woodcraft and Camping, “It ended as nearly all trails do; it branched off to right and left, grew dimmer and slimmer, degenerated to a deer path, petered out to a squirrel track, ran up a tree, and ended in a knot hole.” Even if the route is good, blazes don’t help much if the trail itself has not been cut and is obstructed with deadfall and leaners or clogged with branches or thick growth. Once a trail is established animals will help maintain it: moose and bears do the job best. But if it is not used, the wind-thrown trees, the tops broken off by heavy snows, the new saplings, the alders and willows will all work to return things to their natural state, with only the blazes showing there was ever a path.

Nowadays, of course, a GPS can pinpoint any location but out in the woods I would rather look at the trees than a screen to find my way. And in some public places like parks the trails are now marked with special plastic signs nailed to the trees. Still, I like the old way, and I watch for blazes in any forest. Sometimes I am fooled: among the many marks that animals make on trees there are some which may be mistaken for human sign. Bears and lynx mark their passage by clawing off bark at just the same height, porcupines sample trees here and there, and moose like to polish their antlers by rubbing saplings until the limbs are gone.

The trailblazer is not the explorer or scout who penetrates unknown country for the first time. It is the laborer who follows along, making choices for the best route for others to follow.

Sometimes I come across pieces of forgotten trail and wonder who cut them, when, and why. If they are blazed high on the trees, it shows they were made when the snow was deep and I can guess at their age if the bark has grown thick around the blazes, but they reveal little else. They may follow a stretch of river or a ridge but end at a thicket or a gully where the old-timer decided, wisely, not to cut his blazes before he had definitely chosen and cut the best way through. For really, in our metaphors we use the phrase inaccurately: the trailblazer is not the explorer or scout who penetrates unknown country for the first time. It is the laborer who follows along behind, making choices for the best route and doing the hard work to cut and mark the way for others to follow.