Science and art were tangled up together for Todd Gilens, M.L.A. ’02, ever since the childhood afternoons he spent at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “My father had an office nearby,” Gilens recalls, “and we would go meet him for lunch and walk through the galleries,” which were hung with paintings by Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning—“all these 1960s masterpieces.” But he was even more drawn to the “pools of shiny black” just outside the museum: the La Brea Tar Pits, containing the fossils of prehistoric animals that had fallen in and died there, eons ago. “They had these replicas of a woolly mammoth and a saber-toothed tiger and a giant ground sloth,” he says. “The visit to the art museum always meant climbing on these concrete animals.” A kind of synthesis took hold, “of art and science as both an interior and an exterior experience.”

Decades later, that synthesis was part of what propelled him toward a master’s degree in landscape architecture, after 20 years as a curator, graphic-design artist, set designer, and furniture designer. “I got to a point in my work as an artist where I felt like I needed some traction in a way that I wasn’t quite finding in the arts,” he says. “Landscape architecture has a kind of scientific rigor about it. It’s a discipline that has a basis in both science and the arts.”

That synthesis also runs through Gilens’s most recent work, a public-art project near the south shore of Lake Tahoe, commissioned by the National Forest Foundation. The assignment was simple, but not easy: to create a work that would communicate the processes of forest management: fire ecology and climate change, environmental loss and restoration, adaptability and resilience.

He began by talking to people with a stake in Lake Tahoe’s forests—ecologists and conservationists, real-estate developers, chamber of commerce leaders, skiers and resort owners, and members of an off-road vehicle club in the Sierras. Gilens went on field trips with forestry staff, touring ecosystems and restoration projects. “One trip was a demonstration of forest-thinning machinery on private forest land,” he recalls. “These giant machines would cut down a tree, turn it sideways, strip off the branches, and slice it into 12-foot logs. And then, like spiders, they would waddle through the forest to the next tree and do the same thing.”

He also read hundreds of scientific papers on forest management—fire ecology, insect epidemics, tree mortality, “whatever I could find”—plus poetry, essays, texts in psychology and anthropology and religion: any kind of literature with an ecological theme. He studied Lake Tahoe’s lumber-industry past, how forests there had been stripped nearly bare by the start of the twentieth century, how logging roads were later transformed into access roads for tourists and skiers. As fire suppression became the national parks’ dominant approach to forest management, Tahoe’s vegetation grew back lush. “And so, people’s idea of a healthy forest was a kind of density that historically had not been present,” Gilens says. Even before the clear-cutting, “the original forest was much more open and patchy.” And healthier: uniform lushness actually makes a forest less resistant to disasters like wildfire and drought. A core part of Gilens’s artistic assignment, he says, was to shift mistaken notions about “what a forest is.”

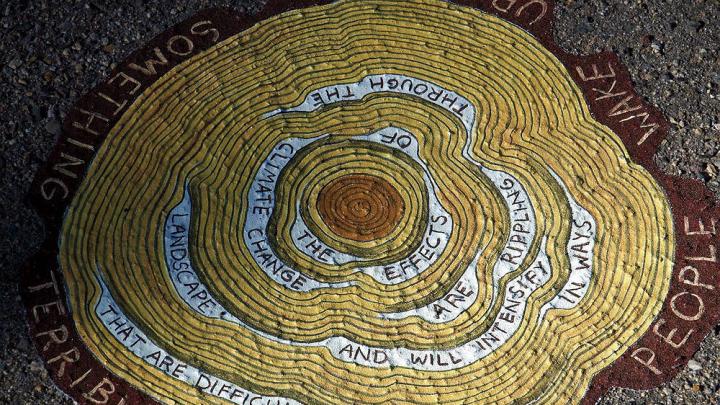

The artwork he devised, on view through November, has two parts. “Postcards to the Future Forest” is a series of six souvenir photographs, available to visitors, that shows the forest blanketed by snow and inhabited by humans, tended by controlled burns and bright yellow tree equipment. The other half of the project, an installation titled “Reading Forest,” merges Gilens’s readings with drawings of trees. The images, photographed and printed on durable sheets of synthetic material placed on the walkways near Tahoe’s western shore, resemble a kind of dendrochronology, with tree rings interspersed with phrases adapted from forays into scientific and literary readings: “Change is always a part of the forest, but not to change too much.” “As life creates the conditions for fire, fire reshapes the living world.” “A pool shines, like a bracelet shaken in a dance.” “The public has been leery of disturbing the forest.”

Gilens created 32 drawings of round cross-sections of trees, representing Tahoe’s conifers and deciduous trees, and ranging from 14 inches to three feet in diameter. The words appear almost like scars in the rings. “Real trees grow unevenly, and things like fires or lightning strikes leave marks,” he says. “What I was doing with these phrases was embedding a disturbance in the regular pattern of growth that changed its shape as I moved toward the outside of the paper. I was countering this vision of a healthy tree ring as perfectly round with a depiction of what is actually a healthy environment, one that’s full of minor to middling disturbances.”

The next project in what Gilens calls his “wiggly career” is a public artwork slated for Reno that also combines science and art and addresses the meaning of place. For several years, he has spent time at ecological field stations in the Sierras, alongside researchers studying chytrid fungus infestations in frogs, or how birds move plant seeds from place to place. For him, “These were all new visions of the landscape,” he says, “just like looking at a manhole cover and thinking, ‘Oh, wow, there’s all this other stuff that happens that we don’t see.’”

One of the field stations contained experimental streams—zigzagging concrete channels that imitate the flow of mountain streams and enable scientists to conduct controlled experiments. To Gilens, who spent four summers surveying streams with one group of researchers, those channels recalled street curbs in cities; he thought about the ties and tensions between natural and artificial worlds—and the in-between places that are neither fully wild nor fully urban. He recalled seeing children floating leaves down a stream of water rushing along a gutter; the landscape-architecture gears began turning in his mind. “The gutter is our temporary stream,” he says. “And the storm drain is that waterfall in the mountains that cascades into a pool and runs downhill. We’ve covered that landscape over, but it’s still there, underneath our houses and streets.”

In 2016 Gilens laid a 23-foot sentence along a street curb in Reno, as a test run for a work-in-progress called “Confluence.”

Photographs by Konah Zebert

The artwork-in-progress he’s calling “Confluence” includes, intriguingly, a mile-long text written in a cursive font borrowed from the handwriting of a deceased federal water master, whose job was to settle disputes over competing water rights. The project’s central idea is to trace the movement of water along the concrete curb, “and your body following that path, too, as you read about how water shapes the land.”

One other way that his art fuses with science: “By the time I was in my mid-thirties, I was making artworks, but it felt more like experimenting.…I didn’t really need to call the work ‘art.’ It was really like, ‘How can I devise an experiment to better understand the experience of this abandoned building?’ Or, ‘What’s the experience of a freeway going through a woodland?’” Or of water flowing wild through a city.