![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

| Previous... Also see What is Yiddish? and A Revival of Yiddish? |

|

Considering the phenomenon of this marginalized and passive minority implanted on hostile soil brings Wisse to what she calls the "fatal complementarity" between the European Jews and their tormentors, which climaxed in the Holocaust. "To what extent might the pacific civilization of the Jews have provoked the anti-Semitism of Germans and Russians? Did the bleat of the lamb excite the tiger?"

Perhaps. But clearly, she stresses, it must never happen again. A people has no alternative to being able to defend itself. "Look. Let's say the Jewish people tried a very noble political experiment. After the Roman sack of Jerusalem, the Jews tried to live for nearly 2,000 years as a people without a land, without a central authority, and without any means of self-defense. They tried to compensate through other means--economic means, for example--for their acute political dependency. But the experiment failed, and they were crushed. This was the problem that Zionism addressed, though not in time to save the Jews of Europe. Still, if the German war against the Jews marks the nadir of Western civilization, the rebirth of the Jewish state is one of its sunniest milestones. It's devastating to see Jews becoming weary defending this splendid, miraculous undertaking."

The continuing war against Israel has aggravated this weariness in many Jews, particularly Jewish liberals, Wisse claims, but theirs is a weariness engendered in great part by a deep-seated moral confusion. In her book If I Am Not for Myself: The Liberal Betrayal of the Jews, she writes of the Jewish "moral strutters," self-designated carriers of a light unto the nations. Strutters, she says, "do not appear to recognize the difference between moral striving...and political scapegoating." They "think they recognize a continuity between the Jew's election to carry the burden of the Law at Sinai and the choice of the modern Jew as a prime target of international discrimination." Like today's liberals in general, they are optimists and rationalists, and they are paralyzed by what Zionism and its enemies reveal about their faith in humanity:

Zionism [Wisse writes] was the last hope of European civilization, for unless Europe could find a rational and just solution to the Jewish problem, Europe itself could no longer pretend to be liberal, rational, or just....From its birth in troubled secular Europe, [Zionism] required an acknowledgement of the destructive as well as the creative impulses of modern society....Zionism required...energetic and significant attentiveness to a small people whose fate exposed the depths of resistance to liberty, equality, fraternity. This is where it ran into trouble at the start, and where it flounders still. Those really infected by hatred cannot confront their own base prejudice, while those others who dream of a benign world order do not want to face the daily manifestation of malice and evil....Jewish self-affirmation has never been an exercise for the weak.

"The character of a nation," she continues, "is independent of its legitimacy, which is what Zionism sought to guarantee. The scandal of Arab rejectionism...half a century after the creation of the state of Israel is great enough. The scandal of Jews who overlook this outrage or accept it as a test of chosenness is an affront not only to Jewish life but to any moral life worth living."

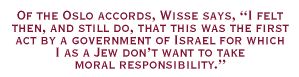

And the Oslo accords? "Like an end to a part of my life. I felt then, and still do, that this was the first act by a government of Israel for which I as a Jew don't want to take moral responsibility. Here, after all that has happened, you hear Jews saying, 'So land, what's land?' Well, what do we want? It was not only the giving up of land that I objected to, but the pretense that this could advance the cause of peace. In fact, no people has ever armed its enemy with the expectation of gaining security. One would do anything possible to free Israelis from having to stand at perpetual alert. But apparently there is no in-between for the Jews. Maybe in 200 years, when--let us hope--the Jewish state is completely accepted, then we Jews can relax our guard."

Her book--and her passionate defense of a strong Israel--have made her a flashpoint of controversy. Hebraist Robert Alter, Ph.D. '62, attacked the book in the New Republic as flawed by "a series of terrible simplifications." On the one hand, he says, "The child of a Russian [sic] Jewish family that very narrowly escaped the Holocaust, Wisse is possessed by a single powerful idea that is palpably rooted in recent historical reality." On the other hand, he continues, Wisse makes no allowance "for the possibility of a tough-minded or pragmatic liberal," and moreover is "convinced that every day is Masada." Edward Alexander, responding in Commentary with the lead, "Ruth Wisse is worth a battalion," reminded Alter of Golda Meir's remark: "We do have a Masada complex. We have a pogrom complex. We have a Hitler complex." Alexander also reminded Alter that three months after Alter himself had proposed in Commentary that Israel "jettison its 'Masada' myth, the Arabs, who showed no evidence of dispensing with their myths, launched the Yom Kippur War and very nearly overran the state."

In speaking appearances, too, controvery clings to Wisse like filings to a magnet. Opening a colloquium at the Kennedy School last fall, the moderator said, "It's probably fair to say that all of you here can be politically defined by where you stand vis-à-vis Ruth Wisse." Some of the hostility that evening did escalate into megawattage. Daniel Pipes rose to her support, as did Martin Peretz. But the coolest participant of all was Wisse herself, who to all appearances thrives on this sort of confrontation.

Such aplomb awes her defenders. Novelist Cynthia Ozick says, "She's just immense. She is my absolute heroine. I don't know how she does it; well, yes I do. It's precisely because she is a scholar-hero who stands very nearly alone on a peak in her scholarship that she is a public hero. Her familiarity with history gives her the courage of clarity. She will stand up even in Harvard Square against every falsehood, distortion, and misapprehension."

All these magnet filings swirl about someone who would rather be a sequestered scholar and a mother-figure than a warrior any day. "It's a privilege to defend Israel," she says. "But it would be a lot easier if more people were doing it." "I feel kind of sorry for her," says Saul Bellow. "She's out there remembering for all of us, but it sort of puts her in a perpetual state of crisis-alert."

The line for her between scholarship and polemics, however, is clearly drawn. "I don't want any of this in my classrooms," she says. "The only legitimate use of the first person plural pronoun in class is 'we students.' 'We Jews' or 'we anything-else' is not an appropriate category in what must be a disinterested, investigative framework. You can understand how difficult it is to maintain this position when everywhere around you these categories have been collapsed. But one is not a propagandist and the classroom is not a pulpit."

Lizzy Ratner '97, a student in Wisse's "Literature and Politics" course, confirms: "I went in there as an advocate of the PLO; my thesis came from totally the opposite end of the spectrum from where she is. I never felt misunderstood or penalized for my views; I felt my views were welcome. We used to get into these big discussions outside of class, like at her house. She actually cooked dinner for us!"

As scholar and polemicist, Wisse takes aim at her bête noir, the culture of victimhood. Many Jews, she feels, wear victim status like a badge, and their victimhood encourages them in problematic undertakings based on wish fulfillment. Like most such questionable endeavors, they often backfire. One example is teaching about the Holocaust, particularly to non-Jews or in a museum setting. Some Jewish organizations, she writes,

expect that imparting information about the murder of the Jews of Europe will ensure its never happening again. Yet almost everything we know about human nature and history would lead to a more obvious conclusion. From the images of Auschwitz and Buchenwald one could derive that: (a) Jews are an easy target; (b) something must be wrong with the Jews if they were selected as a target; (c) it is not a good idea to be a Jew.

As such things happen, Wisse is on the search committee for a scholar to fill the proposed Zelaznik chair in Holocaust studies at Harvard.

Her opposition to the concept of victimhood and all its cognates--as in victim studies--sets her squarely against the greater part of what she calls "the liberal orthodoxy," particularly as it has developed since the 1960s. Recently, in a single essay for Commentary, she mounted a frontal assault on both feminism and the "boutique politics" invented at Harvard and other institutions to circumvent ROTC. To excerpt but one sentence, on feminism:

By defining relations between men and women in terms of power and competition instead of reciprocity and cooperation, the [women's] movement tore apart the most basic and fragile contract in human society, the unit from which all other social institutions draw their strength.

This article--incendiary or cautionary, depending on one's point of view--caught her in the customary cross-fire: on the one hand, she's a crank and doomsayer; on the other, a prophet and voice of sanity. Commentary editor Neal Kozodoy '63 says, "She kind of shatters the eidl-deedl-deidl stereotype of the Yiddishist, wouldn't you say?"

Justin Cammy, a Ph.D. candidate studying modern Yiddish literature with Wisse, respects her aversion to the culture of victimization, especially in Jewish studies. "If there's anyone in the world who suffers because of what happened to the Jews, it's Professor Wisse," he says. "But she is not one to hold up the silent martyr, the weak, the downtrodden as ideals. One of the things you learn from her is to look at Yiddish without romanticizing or sentimentalizing."

"Sentimentality," Wisse affirms, "is a waste. It's demeaning to the culture you're feeling sentimental about. Does all this klezmer and borscht-belt nostalgia tell you anything at all about the actual civilization that existed, about the books people read and wrote, the work they did, what it meant to go to synagogue twice a day, the intimate relationship they had with the Hebrew bible? This is hard stuff and very difficult to retrieve. You know, this is why Jacob Glatstein is 'my' poet, in the sense that the older he got, the grittier he got. Look how he addresses his fellow poets in his poem 'Yiddishkeyt':

Nostalgia Yiddishkeyt is a lullaby for old men

gumming soaked white challah.

Shall we provide the soft crumbs,

the lifeless and hollow words,

we who had dreamed

of new Men of the Great Assembly?

"What I want to share with my students," Wisse continues, "is the vigor of Yiddish culture, not the 'soft crumbs.' The Jews whose lives ended in the ghettos and the trains were not only martyrs. Certainly they were wiped out, exterminated. But what was it that made theirs such an astonishing civilization? You have a literature which was just reaching its point of greatest ripeness; you have poetry, drama, film. You have a tradition that is rising, deepening, broadening, strengthening; in terms of the complexity of Jewish thought and the achievement of Jewish minds, Ashkenazic Jewish civilization represented one of the highest peaks in the history of Judaism.

"I want to share all this, and wherever possible, I want to share it in the original."

Bialik, ir hërt? Do you hear?

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()