Main Menu · Search · Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

|

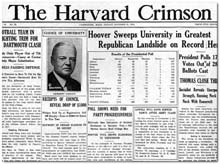

| Straw-poll results in the Crimson, October 31, 1932. Courtesy The Harvard Crimson |

Harvard undergraduates not only failed to support him; they teased him.

FDR was inaugurated on March 4, 1933. Within days he received a letter written

on Lowell House stationery. It stated that the House committee, with the

approval of House master Julian Coolidge and President Lowell, was seeking

permission to designate a "heretofore unnamed carillon of Russian Bells,

at present installed in the tower of our House" as the Franklin Delano

Roosevelt Bells. The bells were real. The rest was a hoax (see "The

Conning of the President," March-April 1995, page 50). FDR wrote an

appreciative note to Coolidge, who had been one of his teachers at Groton.

Coolidge shot back an embarrassed "letter of humble apology" explaining

that the letter was fraudulent.

"Strictly between ourselves," replied FDR, "I

should much prefer to have a puppy-dog or a baby named after me than one

of those carillon effects that is never quite in tune and which goes off

at all hours of the day and night! At least one can give paregoric to a

puppy or a baby. Affably recalling the first class that Coolidge had taught at Groton, he went on to add, "You...announced to the

class that a straight line is the shortest distance between two points-and

then tried to draw one. All I can say is that I, too, have never been able

to draw a straight line. I am sure you shared my joy when Einstein proved

there ain't no such thing as a straight line." FDR, who had a taste for irony, may also have had in mind writer Elmer Davis's pre-election

assessment of him as "a man who thinks that the shortest distance between

two points is not a straight line but a corkscrew."

The new president was the first to bank heavily on scholarly

expertise. "The country is being run by a group of college professors,"

groused West Virginia senator Henry Hatfield. "This Brain Trust is

endeavoring to force socialism upon the American people." The best-known

brain-trusters in FDR's inner circle were from Columbia, but Harvard was

well represented. Professor Alvin Hansen was a principal architect of New

Deal economics. Adolf A. Berle Jr. '13, a former lecturer at the Business

School, was the resident expert on corporate behavior. Law School professor

Felix Frankfurter, LL.B. '06, was an adviser of long standing. He turned

down FDR's invitation to serve as solicitor general, but became known as

"a one-man recruiting agency for the New Deal." FDR later named

him to the Supreme Court. Among Frankfurter's star recruits were Benjamin

Cohen, S.J.D. '16, and Thomas ("the Cork") Corcoran, S.J.D. '26,

two of FDR's most effective aides.

|

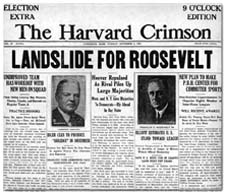

| Four days later, the real winner. Courtesy The Harvard Crimson |

The Transcript man had a point. most of fdr's classmates opposed

him politically, and some loathed him. The standard accusation was that

he was "a traitor to his class." The Reverend Walter Russell Bowie,

FDR's Crimson colleague, spoke of "the rancorous and almost

hysterical political animus which rose against him and what he stood for

among the privileged groups to which many of the Harvard graduates happened

to belong. I was amazed and disgusted to hear the way men talked of him

when he was at the Harvard Tercentenary."

A. Lawrence Lowell, who had charge of the 1936 Tercentenary,

expressed his own disregard for FDR in a correspondence preceding the event.

Felix Frankfurter described the exchange as "incredible among cultured

men and without precedent in this country." Lowell, now Harvard's president

emeritus, begins by addressing the chief executive as "Mr. Franklin

D. Roosevelt." He refers to the upcoming Tercentenary ceremonies as

an "opportunity to divorce yourself from the arduous demands of politics

and political speech-making," and suggests that "it would be well

to limit all the speeches that afternoon to about 10 minutes."

FDR wrote to Frankfurter, "I felt like replying-'if I

am invited in my capacity as a Harvard graduate I shall, of course, speak

as briefly as you suggest-two minutes if you say so-but if I am invited

as President to speak for the Nation, I am unable to tell you at this time

what my subject will be or whether it will take five minutes or an hour.'

I suppose some people with insular minds really believe that I might make

a purely political speech lasting one hour and a half. Give this your 'ca'm

jedgment' and suggest a soft answer 'suitable to the occasion.'"

At Frankfurter's suggestion, FDR writes a polite note seeking

assurance that he is being invited as the president of the United States.

Lowell confirms that he is, adding, "In that capacity I suppose you

will want to say something about what Harvard has meant to the nation,"

and reiterating his suggested time limit of "10, or at most 15 minutes."

"Damn," writes FDR to Frankfurter. He then writes

tersely to Lowell, "Thank you for your letter of April 14. You are

right in thinking that I will want to say something of the significance

of Harvard in relation to our national history. Very sincerely yours, Franklin

D. Roosevelt."

At the September ceremony, FDR omitted Lowell's name from his

opening salutation. He began by stating that he was speaking "in a

joint and several capacity": as president of the United States, as

chairman of the United States Harvard Tercentenary Commission, and as "a

son of Harvard who gladly returns to this spot where men have sought truth

for 300 years." His eloquent speech, partly written by Frankfurter,

took barely ten minutes.

"It was really a great triumph," Frankfurter wired

FDR the next day. "You furnished a striking example of the civilized

gentleman and also of the importance of wise sauciness."

As he campaigned for a second term that fall, FDR made a point

of the fact that his harshest critics were those whose solvency he had preserved

with emergency measures in the darkest days of the depression. "Some

of these people really forget how sick they were," he said in a speech

given in Chicago in October:

But I know how sick they were. I have their fever charts. I know how the knees of all our rugged individualists were trembling four years ago and how their hearts fluttered. They came to Washington in great numbers. Washington did not look like a dangerous bureaucracy to them. Oh no! It looked like an emergency hospital. All of the distinguished patients wanted two things-a quick hypodermic to end the pain and a course of treatment to cure the disease. They wanted them in a hurry; we gave them both. And now most of the patients seem to be doing very nicely. Some of them are even well enough to throw their crutches at the doctor.