Main Menu ·

Search ·Current

Issue ·Contact ·Archives

·Centennial ·Letters

to the Editor ·FAQs

Hate crowds, long lines, waiting lists? You'd have suffered mightily in

the fall of 1946, when Harvard experienced a population explosion of unparalled

proportions. That year's influx of 9,000 war veterans taxed University resources

and altered the size and character of the institution.

World War II had ended in August 1945. An advance guard of 500 veterans,

their tuition fees and other expenses paid under the G.I. Bill of Rights,

had registered that September. A year later the deluge began. The University's

population soared from 3,600 to 11,700. The size of the College rose from

1,782 to 5,400; the prewar level had never exceeded 3,500. The freshman

class of 2,000 was by far the largest ever. Enrollment in the Graduate School

of Arts and Sciences rose from just over 400 to 1,600, the Business School's

student body went from 70 to 1,400, and the Law School's jumped from 162

to 1,500.

|

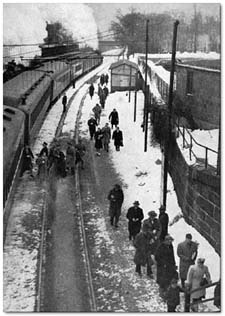

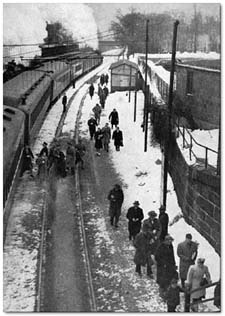

1946: Students housed at Fort Devens arrive by train at Porter Square, Cambridge. Photograph by Walter R. Fleischer

|

The Harvard Alumni Bulletin pondered the plight of the conquering

hero: "After several uncomfortably crowded years in the armed forces,

he is destined for further uncomfortable years at Harvard.Aside from the

inconvenience of living quarters which may be located at considerable commuting

distance from Harvard Square, he will have to be satisfied with crowded

classrooms and all the haste which goes with a University enrollment of

12,000 men, a third larger than the previous peak year. His $60 or $90 a

month will not go so far as a year ago in a community where sodas now cost

25 cents and suits $50; where a single furnished room is $32 a month and

an apartment $75. But he has come, he is welcome, and we wish him the best

of luck. We can take him if he can take us."

American educators had anticipated rising enrollments after the war, but

nothing like this. Student housing was now their number-one problem. President

James Conant sent letters to 16,000 local alumni asking for help in sheltering

some 3,000 married vets and their families. His appeal elicited 99 offers

of space. The widow of an alumnus proffered a room in her Brookline home

for $10 a week. That sum, she explained, would be added to the salaries

of her two maids. Meals and services would be provided; if meals had to

be served at odd hours, they would be. If the cook didn't like the arrangement,

said the widow, she'd fire the cook. Another Brookline homeowner offered

to consign his garage to a naval officer and his wife, provided the wife

washed up for the household. Done and done. Other offerings included a sanatorium

and two country clubs.

Before registration day in 1946, some 300 students who lived within 45 minutes

of Harvard Square were notified that they would have to commute till the

housing crisis abated. The basketball court of the Indoor Athletic Building

was commandeered as a dorm for single students. Each was issued a "cot,

chair, and ashtray."

Almost 200 of the married veterans were housed in 33 one-story frame buildings

shipped by the government from South Portland, Maine, where they had been

erected for wartime shipyard workers. The buildings were reassembled on

lots near the Divinity School, the Business School, and Memorial Drive.

About 400 families bunked at Fort Devens, in the outlying town of Ayer,

a three-hour round-trip train commute via Porter Square station. Their sector

of the army camp was dubbed "Harvardevens Village." Another 115

families lived in apartments at the Hotel Brunswick in Copley Square, which

Harvard leased for three years.

The veterans were eager to learn. Faculty members admired their seriousness

of purpose, disciplined work habits, and broad perspectives. Their differing

economic and social backgrounds, war experiences, motivations, and values

set the vets apart from the relatively homogeneous and more casual student

body of prewar days, and made Harvard a more pluralistic institution. For

the teachers and the taught, the years just after World War II were an exhilarating,

rewarding, often joyous time-crowded quarters and long lines notwithstanding.

~ Primus IV

Main Menu ·

Search ·Current

Issue ·Contact ·Archives

·Centennial ·Letters

to the Editor ·FAQs

![]()