Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

|

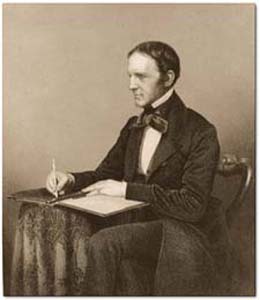

| Prescott using a noctograph, a kind of mechanical ruled slate on which he did most of his writing. Illustration courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society |