Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

Barbara Fash oversees the painting of Rosalila, in colors faithful to the original. |

Some of the original sculptures carved at Copán have already deteriorated badly. Abundant ground moisture-which both pine trees and coconut palms, growing side by side, find congenial-causes the sculptures to decay at the base. "Furthermore," says Bill Fash, "the city is cursed to be in the center of an earthquake zone. Ancient Copán was founded around a.d. 400 in the midst of the area's most fertile farmlands," he explains. "As the city prospered, its population grew to 20,000, outstripping local resources. Tainted water and reduced areas of productive land led to increasing dependence on vassal towns, which broke off their relationship with the Copán kingdom precisely when they were most needed." The city was toppled by tremors in antiquity, after the kingdom had collapsed. A single 1934 earthquake reduced four buildings on the Copán acropolis to rubble, and broke the

A wall from Temple 26, with casts (in white) of original stones taken to Harvard's Peabody Museum in the 1930s. Carved in two different scripts, the wall is the Mayan equivalent of the Rosetta stone. |

What can't be restored can at least be recreated-that will be the legacy of the early archaeological expeditions. "Local artisans can replicate originals, sometimes better than they now exist, by working from drawings and photographs of the sculptures before they started to wear," notes Fash. The artisans grind up a light green volcanic tuff, from which the originals were also carved, to color their cement casts.

But Fash has mixed feelings about the overall impact that the dig has had on village life in Copán.

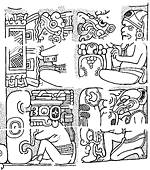

David Stuart's line drawing of four glyphs shows the intricacy of Mayan writing. |

According to Fash, some Maya traditions are still observed in Copán. Respect for the ancient culture is widespread. During preparations for one of the museum exhibits, an ancient god seemed to awaken from a long slumber. Barbara Fash, colleague Karl Taube, and local workers were reconstructing a sculpted panel of the Central Mexican storm god, to whom the kings of Copán swore fealty. Originally set up on a temple stairway, the panel had been torn apart 1,100 years before, probably to get at the offering of jade, incense burners, and spiny oyster shells behind it. "When we reassembled it," says Barbara Fash, "all of a sudden a huge storm blew up. The wind, lightning, rain, and thunder were so loud that you couldn't talk. It came out of nowhere. The local workers dropped what they were doing-they were terrified," she says. Carved skulls, representing sacrificial victims, which surrounded the stairway panel added to the effect.

Barbara Fash, who could probably put Humpty-Dumpty together again if she set her mind to it, oversaw construction of the museum exhibits, which include six complete building façades and pieces of sculpture from 19 others. Rosalila was chosen as the centerpiece because it dramatically illustrates

Abundant natural light brightens the museum interior. |

An important contribution also came from the Peabody Museum. The Maya analog to the Rosetta stone is an interior temple wall carved in paired columns of glyphs in two different scripts, one Mayan, the other from the Central Mexican town of Teotihuacaan, the "City of the Gods." Harvard archaeologists had collected 25 pieces of this wall in the 1930s. David Stuart, the associate director of the Peabody Museum's Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphs Project, pieced the fragments back together with Barbara Fash, who made molds and brought them to Copán. There she made casts, completing the wall from Temple 26, now nicknamed "the Harvard wall."

At the museum's August 1996 dedication ceremony, attended by the presidents of Guatemala and Honduras, the townspeople of Copán gave Barbara Fash a seven-minute standing ovation. They knew how long and hard she had worked to piece the buildings back together. The museum's central module is now complete. Six more are planned, the first of which will house the hieroglyphic stairway (a dynastic history of the kingdom's rulers), a project even more complex than Rosalila (which took three years to build). As the Fashes well know, there are decades of work yet to be done-fitting tribute to a kingdom that prospered for more than 400 years.

Jonathan Shaw '89 is an associate editor of this magazine.