Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

| The Floodlit Night Sky | The Stalker's World | |

| Violent Chimps | A Sports Doc for the Geriatric Jock | |

| E-mail and Web Information | ||

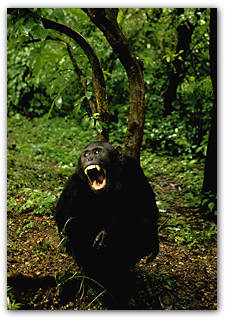

In a verdant setting, an African chimpanzee vents frustration.Photograph ©Gerry Ellis/Ellis Nature Photography |

During a series of genocidal massacres in Rwanda and Burundi that at one point left 10,000 human bodies floating ashore on Lake Victoria, a Harvard anthropologist traveled to war-weary Central Africa to investigate the origins of human violence. But instead of studying the fighting Hutu and Tutsi tribes, professor of anthropology Richard Wrangham plunged into the "time machine" of the rainforests to examine Homo sapiens' closest genetic relatives, the chimpanzees and pygmy chimpanzees, or bonobo apes.

In a new book, Demonic Males (Houghton Mifflin), which Wrangham wrote with science writer Dale Peterson, he reveals how he found a glimmer of hope that humanity could reduce its violence and overcome its five-million-year rap sheet of murder and war. Wrangham bases his optimism on the discovery that bonobos create peaceful societies in which males and females share power--while the biologically similar chimpanzees live in patriarchal groups in which males regularly rape, beat, kill, and sometimes even drink the blood of their own kind.

Wrangham's theory is that human civilization would be more civilized if women seized more political power through elections and used it to counterbalance the male instinct to constantly define "enemies" and attack them. To make this advance, however, women must first abandon a tendency they share with female chimpanzees: to reward and select aggressive males as their mates. "The example of the bonobos reminds us that females and males can be equally important players in a society," says Wrangham. "And by giving us a model in which female action works in suppressing the excesses of male aggression, the bonobos show us that in democracies like our own, women's voices should be heard more than they are."

Perhaps the most revolutionary discovery that Wrangham and other researchers have made through patient observation of Central African apes is that warfare is not uniquely human. Scholars had long thought that it was. As recently as 1987, an international group of 20 distinguished scientists signed what they called the Seville Statement on Violence, declaring that war "does not occur in other animals" and is almost entirely "a product of culture."

But as early as 1974, researchers in Gombe National Park in Tanzania had been startled to observe chimpanzee males organizing gangs of a half-dozen or so members and launching lethal raids into the territory of neighboring chimps. These were clearly not food-gathering expeditions. The chimps did not stop to eat, and they did not make any of their normal calls and shouts. Instead, they crept silently into the territory of a neighboring group and hid until they saw a lone chimp. Screaming with excitement, they would ambush the victim, hold him immobile and beat him to death, sometimes twisting the victim's leg until the muscles ripped, or tearing off flaps of skin while he was still alive. In one well-documented case in Tanzania, a group of male chimpanzees used such ambushes to eliminate a whole band of neighbors.

Further research found that such violence was not limited to chimpanzees. Male gorillas, for example, were observed ripping infants out of their mothers' arms and smashing them to the ground in often-successful attempts to entice the mothers to mate with them. One theory is that the male gorillas do this to demonstrate their strength and to show how valuable they would be as protectors.

Violence is present in every human culture, from contemporary New York City to the primitive Waorani people of the Andean foothills, whose frequent raids on each other cause a startling violent-death rate of 60 percent, according to anthropologists Clayton and Carole Robarchek. Given these facts, it might appear that the primate family tree has blood in all its roots. But anthropologists were happy to discover more restrained behavior among the bonobos. Living principally in Zaire, bonobos are slightly smaller than chimpanzees and make calls like twittering birds. Genetically, these apes are more closely related to human beings than they are to orangutans.

Although bonobo males are occasionally aggressive, they are usually discouraged from killing or raping by tight-knit bands of females that gang up on and attack aggressive males. The glue for these closely bonded groups of females is regular female-to-female, missionary-position sex, Wrangham writes. Such female-to-female sexual bonding is thought to be unique in the nonhuman animal world.

Wrangham avoids drawing close parallels between bonobos and human beings. He doesn't believe, for example, that lesbianism is the answer to human warfare. Instead, he takes a broader look at the species' behavior patterns, seeing female bonding and alliance-building in general as a weapon against the dominance of violent males. "I believe that Fyodor Dostoevsky got it right in The Brothers Karamazov, when he wrote that we all have a demon in us," Wrangham says. "And I can only hope that by understanding this, we can reduce this demon a little bit."

~Tom Pelton