![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

Prime targets of the Foundation Fighting Blindness are retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and macular degeneration, which is, in a sense, the converse of RP because it primarily affects the cones at the center of the retina. In our aging society,

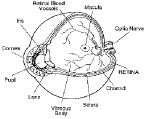

Retinitus pigmentosa and macular degeneration affect photoreceptors of the retina. |

The largest single recipient of funding from the foundation is the Berman-Gund Laboratory at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, which alone has received more than $9 million. Since its inception in 1974, Chatlos professor of ophthalmology Eliot Berson, M.D. '62, has headed the lab. Cabot professor of natural sciences John Dowling '57, Ph.D. '61, a neurobiologist specializing in the retina, says that Berson and his colleague Ted Dryja, Cogan professor of ophthalmology, have made genuine breakthroughs in understanding RP; Dowling calls Berson "the most knowledgeable person in the world on RP." The foremost clinical advance in RP treatment derives from Berson's 1993 findings, from a six-year study of 600 adult RP patients, that large doses of vitamin A could slow the progression of RP by 20 percent, and thus provide seven additional years of useful vision to the average patient. Although the therapeutic mechanism is unclear, Berson speculates that "vitamin A may provide benefit by rescuing remaining cone photoreceptors."

Though the 20 percent slowdown is significant, "We want to slow it 99 percent," says ophthalmologist Alan Laties, who chairs the foundation's scientific advisory board. Genetics holds the key, since hereditary factors cause at least half the diagnosed cases. Researchers have so far isolated 17 defective genes associated with photoreceptors; Berson says patients with the same gene defect "may show differing severity of disease depending on where the mutation falls." By injecting human DNA into a fertilized mouse egg, researchers can create "transgenic" mice that carry the same mutations as humans with RP. Using such animal models, researchers at the University of California Medical School in San Francisco have shown that several neurotrophins can favorably affect retinal degeneration in both transgenic and spontaneous mutations. And Johanna Seddon is currently studying a group of elderly twins to tease out the genetic and environmental components of macular degeneration.

"Most mutations are recessive," says Dowling. "But often you get dominant-inherited diseases--in other words, if you have one defective gene out of two, you get the disease." Disorders like RP and macular degeneration that often manifest themselves after the reproductive years are not culled from the gene pool by natural selection. "Any family could have a child with RP," says Berson. "It's estimated that anywhere from 1 in 80 to 1 in 50 Americans is silently carrying an RP gene. The majority of patients have normal parents." None of Gordon Gund's blood relatives has had the disease, and his sons underwent a highly reliable screening test as youngsters that showed no indication of RP.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()