Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

| The Multiracial Option | Cortisol Kids | |

| Purging Stereotypes | California Conflicts | |

| E-mail and Web Information | ||

|

You don't have to be a white, well-educated, upper-middle-class woman to suffer from eating disorders. Poor women, immigrant women, Hispanic, African American, Native American, and Asian women are all at risk for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, according to assistant professor of medical anthropology Anne Becker '83, M.D. '87, Ph.D. '90, director of research and training at the Harvard Eating Disorders Center. Contrary to popular misconceptions, so are men.

The center recently sponsored a forum at the Kennedy School of Government on "Culture, Media, and Eating Disorders," where panelists explored emergent demographic trends and debated the impact of cultural imagery. One surprise: about 10 percent of anorexics and bulimics are male--as are 40 percent of those with binge-eating disorder. "Such data challenge the stereotype that these are disorders of affluent women," Becker says, to emphasize that if physicians and others don't believe eating disorders affect other groups, many individuals may not receive proper treatment.

Also unexpected were recent data suggesting that poorer women may actually have a higher incidence of bulimia than women of higher socioeconomic status. A 1996 review in the International Journal of Eating Disorders of two decades of studies that included assessments of socioeconomic status found that 13 studies since 1983 have reported no relationship between high socioeconomic status and eating disorders, and five of those studies, in fact, showed an inverse relationship. The review also cited a 1987 study of subjects from nine communities in eastern Massachusetts that found bulimia nervosa significantly more common among lower-income women than among wealthier women.

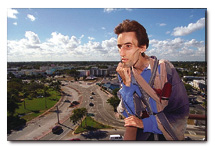

About 10 percent of anorexics are men, like 5-foot, 9-inch Michael Krasnow, who weighs 75 pounds.CANDACE WEST

About 10 percent of anorexics are men, like 5-foot, 9-inch Michael Krasnow, who weighs 75 pounds.CANDACE WEST |

Another survey found eating disturbances equally prevalent among Hispanic and Caucasian females. But surveys also show that these syndromes do not affect all groups in the same way. For example, being overweight puts minority women at a greater risk for eating disorders, while perceiving oneself as overweight is likely to increase the risk for Caucasian females.

Minority women receive the cultural message that "thin is beautiful" just as white women do, Becker says. But she suggests that women of color may feel doubly marginalized: not only are they a minority in society, but their bodies may not fit the type shown in fashion magazines. Indeed, a 1987 study indicated that immigrant women may have a heightened risk of developing eating disorders. "Since the media may be an important part of their limited exposure to local cultural values, [minority] women may have an especially difficult time viewing [such images] critically," Becker wrote, in collaboration with Paul Hamburg '67, in a recent issue of the Harvard Review of Psychiatry.

Panelists at the forum also examined the complaint that the media perpetuate eating disorders by promoting a belief that women must resemble fashion models. Elizabeth Crow, editor-in-chief of Mademoiselle, defended fashion magazines from the wave of criticism. "Nice people attempt to rip my throat out," she said. "People forget that fashion is entertainment, not reportage." But one woman in the audience, a resident adviser at Harvard College, countered, "Do you care that readers are not that sophisticated--that they don't see it as entertainment? My kids want to look like Kate Moss. They think they look chubby--and they're not."

~ Susan G. Parker

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()