![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

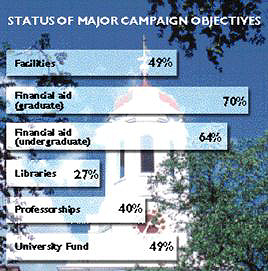

The University Campaign has raised 74 percent of its $2.1-billion goal, but funds for several academic priorities lagged behind as of this spring.Chart by Stephen Anderson

The University Campaign has raised 74 percent of its $2.1-billion goal, but funds for several academic priorities lagged behind as of this spring.Chart by Stephen Anderson |

With three years down and two to go before its planned mid-1999 conclusion, how fares the $2.1-billion University Campaign? Strictly by the numbers, very well--thanks to more than 120,000 donors to date--reports Thomas M. Reardon, vice president for alumni affairs and development. Director of development Susan K. Feagin projected in late May that gifts and pledges might total $1.54 billion by June 30, the end of Harvard's fiscal year. That represents nearly 74 percent of the campaign's goal, a pace six months or more ahead of the fundraisers' expectations.

"It's been a great time to be in a fund drive," says Reardon. By felicitous coincidence, the academic planning process that established goals for the campaign concluded just in time for the fundraising, launched in May 1994, to take advantage of sustained growth in the U.S. economy and financial markets. Those robust conditions also make it easier for donors to fulfill pledges: Feagin says more than $1 billion has actually been received, well ahead of expectations (see "Dreams Deferred," May-June 1996).

But there is another way to tell the story. Most campaigns meet their aggregate goals, the development officers say. More challenging, according to Feagin, is matching gifts to the "academic priorities the president and deans set out" in the planning process. Educational fund drives rarely satisfy all their academic goals, she says, but--given this campaign's momentum--adds, "We see the opportunity, at least, actually to meet the priorities" Harvard has established.

As of March 31, income totals for individual campaign objectives showed wide variations (see graph). Funds for financial aid are generally forthcoming: the Divinity School, for example, has raised only about 60 percent of its $45 million target so far, but will reach its financial-aid goal this year, says Dean Ronald F. Thiemann. The tradition of strong donor support for financial aid across the University, says Reardon, reflects the fact that "People like to do things with people."

Proof of which, perhaps, appears in the results to date of efforts to secure resources for Harvard libraries: barely one-quarter of the amount sought has been pledged. That shortfall apparently surprises no one. Libraries always present a challenge, says President Neil L. Rudenstine, recalling that when he was provost at Princeton during a capital campaign, "The libraries came in last." Jeremy Knowles, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), referring to the need to rebuild Widener's infrastructure, says the opportunity of naming "a memorial air-conditioner" holds "very little resonance" for most prospective donors. Nor does paying to store deteriorating books in digital media or to build a next-generation electronic catalog. "There is nothing more important than the major university library in the country," says Robert G. Stone Jr. '45, a member of the Harvard Corporation and cochairman of the Campaign, but compared to other needs, it has "no sex appeal."

On the other hand, the campaign has exceeded expectations for one of its chief "nonpeople" goals, funding for facilities--where the opportunities for naming are obvious. Rudenstine says he is particularly surprised by support for major renovations such as the Memorial Hall-Loker Commons project and the transformation of the Union into the Barker Center. (The humanities departments began moving in just before Commencement; Harvard Magazine will report on the building in the next issue.) Those projects, new buildings at the Law School and the School of Public Health, and construction of the new racquets facility at the athletic complex are, in fact, the most tangible signs of the campaign's progress. With planning underway for new computer sciences, regional studies, and chemistry facilities, Reardon says that FAS is fully absorbed by its current building priorities--yet funds are still being sought for a government-department building and the renovation of Littauer for the economics department.

Even as faculty offices are being improved, funds to pay for new professorships are proving somewhat scarce. The divinity school has been able to create new chairs in evangelical theology and world Christianity, but two others--in Islam and Asian religions--remain as yet unfunded. FAS, which ambitiously aims to create 40 new professorships concentrated in the areas of greatest teaching demand, such as philosophy, the fine arts, government, and music, thus far has met less than half its goal. One obstacle is price: new chairs cost $3.5 million. Another is matching the dean's desires with donors'; Knowles acknowledges that some of the 18 chairs pledged to date are "in areas of donor interest but not compelling teaching need."

Stone, who has been down this road before--he cochaired the 1979-1985 Harvard Campaign--says that the faculty goal is attainable. He also points out that contributions for other purposes, such as the decision by Thomas F. Stephenson '64 in 1994 to endow the position of football coach, release unrestricted funds for academic purposes identified by the deans. "That's just as important to Jeremy [Knowles] as a faculty position," Stone says. "It's all the same budget." Knowles agrees that such dedicated gifts "relieve the spending of unrestricted dollars and so allow the relieved funds to be directed at essential if less attractive needs." In fact, he says, this summer FAS will begin work on expanding faculty ranks as campaign funds already received free enough unrestricted income to create a dozen or more professorships even before dedicated funds have been raised for them.

Finally, the quarter-billion-dollar University Fund stands out as a test of the campaign's ultimate success. The fund is intended to support the five interfaculty initiatives; provide the president with seed money for new academic ventures; and serve as backup support for libraries, graduate fellowships, and necessary information technology, particularly at the less well endowed professional schools. Securing such gifts, says Reardon, requires asking donors to invest in "the future leadership of the University." Stone, emphasizing the importance of such discretionary funding, says the low results to date are partly by design, because the president places a higher priority on reaching the deans' goals first. But even as he says that raising the next $300 million "is the hardest" part of the whole campaign, Stone vows of the University Fund, "We can do that."

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()