![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

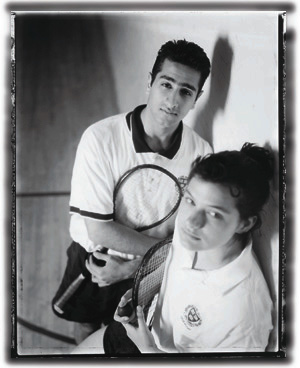

Seniors Daniel Ezra and Ivy Pochoda currently play at number one for the men's and women's squash teams at Harvard. Both squads have dominated intercollegiate squash in the 1990s.Photograph by Erik Fowke

Seniors Daniel Ezra and Ivy Pochoda currently play at number one for the men's and women's squash teams at Harvard. Both squads have dominated intercollegiate squash in the 1990s.Photograph by Erik Fowke |

Cautious Superstars

Several years ago, head squash coach Bill Doyle had a problem: a couple of his top players were acting more like stars than team members. When hitting with a teammate lower down the ladder, the top player would quickly wear the other man to a frazzle, rather than easing up a bit so his teammate could pace himself and get a good workout. At a tournament in New York, a number 4 man from Princeton upset one of the Harvard luminaries, who, perturbed, announced that he was leaving immediately for Cambridge, rather than returning with the rest of the squad on the team van.

"I was going to boot the two top players off the team," Doyle recalls. "I went to the team captains, who were aware of the situation, and asked, 'Are you prepared to lose without them?' Once you take away the fear of losing, you can make the right decision." (Lost matches are no small matter in Harvard squash; the men's and women's teams are 135-1 under Doyle.) The captains replied that if the top men were unwilling to be team players, they were indeed willing to let them go, despite the likelihood of losses.

"Some coaches say that you have to treat your top athletes differently," Doyle continues. "I don't agree. You may have to coach them differently, but they shouldn't receive any special privileges or exemptions as team members." The coach confronted his star players with a "shape up or ship out" ultimatum. The stars decided to shape up, eventually thanked Doyle for the chastisement, and led the Harvard squad to yet another undefeated, national championship season.

What happens to a young athlete who, early on, becomes a one-sport specialist, trains hard year-round, invests years in building a high level of competitive skill, and then arrives at an elite college as one of the top players in the nation? "By the time they get to college, they may feel entitled to X, Y, and Z by virtue of being great athletes, by being able to score points," says Frank Haggerty. "The converse is, that there is less and less sense that a spot on a team should be earned--as opposed to assigned. The 'entitlement' philosophy may also show up as a lack of respect for officials--'What do you mean, kick me out of the game? I'm the reason people are in the stands.'"

Tennis coach Dave Fish speculates that "Athletes may be less self-reliant today; they have had to do fewer things for themselves. Society so appreciates winning that it lays out a program to produce winners: Little League games every third day, camps for elite soccer kids. Parents wake the kid up to make sure he gets to his tennis match on time. Parents enter you in tournaments; otherwise you'll miss the junior nationals and you won't get a scholarship; it's end-oriented now, not process-oriented. Later, the coach is expected to do things for the player. Kids think that with the coach's blessing they'll get into Harvard: they expect that because they have worked so hard, there's an automatic payoff. I've had kids be upset when I didn't say, 'I'll get you in.'"

Three-letter woman Char Joslin '90, wielding a lacrosse stick.Photograph by Tim Morse

Three-letter woman Char Joslin '90, wielding a lacrosse stick.Photograph by Tim Morse |

The ethos of specialization and the emphasis on winning may also breed a peculiar form of conservatism and timidity in young athletes. "There is an invisible pressure on them," says Maura Costin Scalise. "They are so used to being great swimmers and great academically that they don't want to try something new. They want to excel at something or not try it at all. They don't want to risk a new event. Over the last 13 years, I have had to change my coaching to tell people, 'It's OK to try new things, to make mistakes, to fail.' The expectations that they have for themselves are so high that it stops them from having fun.

"And they are afraid to ask for help. That would show that they are not knowledgeable--in swimming, or socially, or academically," Costin Scalise continues. "But after four years with your friends, having your niche in the sport, you suddenly have to go into the real world. If you don't take chances, how do you know what you want to do? People are going to be frozen if they can't say, 'Wall Street doesn't work for me.'"

Doyle emphasizes that he wants team players, "not just a bunch of national squash champions who come to practice. I don't want McEnroe to come here for a year and then leave; that takes away the spot of someone who would be here for four years." (John McEnroe attended Stanford as a freshman in 1978, dominated college tennis, then left to turn professional.)

The structure of competition can also spotlight star individual performances while eroding group endeavor. "Track and field has become less of a team sport," says Haggerty, who regrets the decline in the number of dual track meets. In the 1960s the team would have 10 to 12 dual or triangular meets per year; today there are five or six. Other than the Heptagonal championships, Harvard's dual meet with Yale was the only outdoor scored meet this year. "If you don't have a dual meet record of 5-0, then the team's performance starts to become a question of, 'How many people did you take to nationals?'" Haggerty explains. "So the tendency is to go to a meet where there will be a strong field in, say, the 5,000 meter race--but you can take only four or five athletes to a meet like that. You begin to develop a star system. This stunts the development of other athletes who might come on if given the chance."

The God of the Won-Lost Column

"Winning is an obsession in this country," says John Dockery. "The Buffalo Bills make it to the Super Bowl four years in a row, each time they're the conference champions--but the idea is, 'If you don't win, you're a loser.'" In today's highly competitive environment, where athletic performance and personal identity sometimes converge, losing at college sports is less acceptable than ever, and winning more worshipped. "There's more pressure to win in all our jobs," says Tim Murphy. "We seem to be an immediate gratification society."

Professional sports franchises, where ticket sales and TV ratings mean huge profits or losses, routinely fire coaches whose teams lose. Today, that trend has trickled down to colleges. "College soccer coaches are losing their jobs because they're not getting it done in the 'W' [win] column," says Steve Locker. "When that happens, you know you have arrived as a sport. It also means some coaches will lose perspective on what college athletics is about, and begin to sacrifice their principles in order to win games." Incentive clauses for winning are common in coaching contracts in Division I athletics--like giving a basketball coach, for example, extra stipends for reaching the NCAA tournament, tiered by how many rounds the team wins. Such deals could potentially put a coach's personal interests in conflict with those of the athletes. Jeff Orleans, executive director of the Council of Ivy Group Presidents, says, "I haven't surveyed all 250 head coaches, but I would strongly doubt that such arrangements exist in the Ivy League."

Still, Ivy athletes seem to be extending themselves to greater, and perhaps dangerous, lengths in pursuit of victory. In the fall of 1995, in the first half of the Harvard-Cornell men's soccer game, the Crimson's two best defensive players, John Vrionis '97 and Lee Williams '99, were both seriously injured. Both were in the air, going for head balls, and were hit from behind by Cornell players. Cornell won, 1-0 in overtime, but the two Harvard players lost the rest of their season's play, Vrionis with a broken ankle and Williams with a torn knee ligament. "Of all the games played in the past two years, Cornell has been the most physical--more injuries, more fouls, more cards," says Vrionis. "It always ends up being a bit of a bloodbath."

That may be simply coincidence, but the intensity attached to winning does raise both the stakes and the risks. "I've played soccer for 30 years and have never been injured once," says Locker. "In an effort to win, some coaches think they are having success when their players get 'stuck in' [tackle opponents hard, with spikes high]. Coaches permit it and even promote it to some extent. Referees are not expert enough to see and call everything, and they don't want to be blowing whistles every minute, they want to let the game flow. Without a doubt, the injury rates are higher than they used to be. There's an increased disrespect for players' well-being, and there's no question that is a consequence of the increased pressure to win."

The worship of the won-lost record may also lead to developments like large rosters that allow a team to turn over its lineup each year, rather than nurturing the same individuals for four years. "The playing field has changed in the Ivy League," says Costin Scalise. "Some schools have highlighted a few sports." Last year Princeton had 43 women swimmers, Yale 38, and Harvard 17. "I can't compete with that," Costin Scalise says. "They replace their swimmers after they swim for a year or two. But my swimmers swim faster every year."

No doubt other colleges also perceive Harvard as focusing on certain sports--rowing, ice hockey, and squash, for example, have long histories of success. Nor is there any question that Harvard loves to win, and its athletic director, Cleary, is surely one of the most competitive individuals in the Western Hemisphere. He coached a highly successful hockey program for two decades, capped by a national championship in 1989. Rowing coach Harry Parker's men's heavyweight crews have won more national titles than any other college, and just this past year, the men's and women's lightweight crews were national champions. Both squash teams have been nearly invincible, the women winning six consecutive national titles, and the men seven. Carole Kleinfelder's women's lacrosse team were NCAA champions in 1990, Char Joslin's senior year.

But at Harvard, winning is not the sine qua non. Take men's basketball, a sport where the Crimson have never been a power, and have never won an Ivy crown. When Frank Sullivan began as head coach in 1991, he inherited a program whose last winning season was in 1985. Sullivan's first year was hardly auspicious, as the team went 6-20. But after that year, Cleary declared, "I'm more sure than ever that I made the right decision in hiring Frank"--based on how well Sullivan had handled the tough campaign, and how he had related to his athletes. Last winter, in Sullivan's sixth season, the basketball team went 17-9, notching the most wins by a Harvard squad in half a century. At many colleges, Sullivan would never have reached that sixth year.

"Here, we want to win, but we don't have to win," says soccer's Tim Wheaton. "Harvard is one of the best places to coach in the country because there are no pressures put on you," says Costin Scalise. "The individuals you coach--your athletes--are the ones you are reporting to." This atmosphere grows from Harvard's long-established philosophy, strongly upheld by Cleary: "You are an educator first, and a coach second." Last fall, the men's soccer team had the highest grade point average of any men's soccer program and, Locker says, "I'm more proud of that than getting to the second round of the NCAAs."

The primacy of education over athletics is a philosophy shared throughout the Ivy League. For example, the Ivies are the only basketball conference that plays its games back-to-back on Friday and Saturday nights--to minimize missed class time. But even within the Ivies, some are eyeing greener pastures. "It's important for us to think of 'winning the Ivy League' as winning," says Harry R. Lewis '68, Ph.D. '74, dean of Harvard College, who chairs the Faculty Standing Committee on Athletic Sports. "There is a sort of mental shift I feel happening, that 'winning the Ivy League is great, because now you can go into the real competition.' That's an attitudinal change with some regrettable consequences: when you focus on postseason play, you start doing things without any real educational significance--like rearranging your schedule to maximize its strength-of-schedule rating."

Currently, the Ivy League basketball champions get an automatic bid into the NCAA tournament--a fact that enabled Princeton to upset UCLA two years ago. But in recent years there has been a proposal to have a postseason Ivy League basketball tournament--eight teams, three rounds, single elimination. The winner would represent the league in the NCAAs. No college would be out of the running until the very end. But in essence, this proposal would make the Ivy basketball season a seeding process for the postseason tournament. So far, the league has not adopted the basketball proposal. It could, however, be a source of some revenue. And, of course, a longer season.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()