![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

|

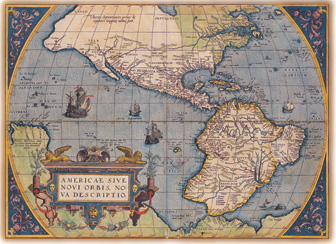

Above: A year after Gerhard Mercator released his famous projection, which translated a spherical Earth into a flat map, his friend and cartographic rival, Abraham Ortelius, published the first modern atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Amsterdam, 1570). Ortelius gathered 70 maps by different makers, maps he re-engraved at proper scale for his atlas. The map collection has that book, but the plate reproduced here is from the first colored edition, issued in 1581. The atlas went through 40 editions, persisting well into the seventeenth century. |

"Anything that can be spatially conceived can be mapped-- and probably has been," write Arthur H. Robinson and Barbara Bartz Petchenik in The Nature of Maps. "The concept of spatial relatedness, which is of concern in mapping and which indeed is the reason for the very existence of cartography, is a quality without which it is difficult or impossible for the human mind to apprehend anything."

For that reason, writes John Noble Wilford in The Mapmakers, "the uses of maps in human communication continually increase and diversify, reflecting the range of interests, knowledge, and aspirations--of what can be or should be 'apprehended.'"

Apprehending proceeds apace at the Harvard Map Collection, housed in Pusey Library. Here are 400,000 maps on paper, 6,000 atlases, 5,000 reference books. The collection is the oldest in the United States and among the finest at any academic institution in the country. It was founded formally in 1818, but of course Harvard had been collecting maps from its beginning. Now the staff is entering the digital arena. How could they not when a single CD-ROM contains an up-to-date street map of every city and town in America?

The collection is used extensively for teaching and learning. Philip M. Sadler, assistant professor of education, and F.W. Wright, lecturer on navigation, who teach Astronomy 2: "Celestial Navigation," take their students to the collection to learn what early artifacts can tell about the development of navigation. "I show my students a celestial map some 350 years old," says Sadler. "It has in its margins depictions of competing theories of how the universe behaves--Ptolemaic, Tychonic, Copernican. My students see that at the time Harvard was founded, scholars weren't sure what revolved around what."

Some people use the collection to plan their vacations. Indeed, if you have a jot of imagination, merely gazing at a map transports you. Ah, there's Paris! Ah, sixteenth-century Dubrovnik! Ah, terra incognita! Gazing at the Harvard Map Collection can leave you widely scattered. Over continents. Into the sea. Through the heavens. Deep in the 1921 Greater Boston sewer system. "We collect almost all types of maps," says reference librarian Joseph Garver, "with the exception of geologic maps, the sphere of the geological sciences library. We have traffic-volume maps, flood-insurance maps, helicopter-route charts, maps of gas pipelines, of hazardous waste sites, of seismic activity, even of microbreweries."

|

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()