![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

|

The secretary of the Harvard class of 1871 once wrote to William Sturgis Bigelow requesting some news, "or a story." Bigelow replied, "Story? God bless you, I have none to tell, sir. Since '81 I have spent about seven years in Japan, when [sic] I saw a great many folks of high and low degree, got together some things of various sorts for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts...and learned a little about Eastern philosophy and religion. I have neither wife nor children, written no books, received no special honors and I belong only to the regular clubs and societies."

This extraordinary understatement combined Buddhist self-abnegation with the inner confidence of an affluent, private, and talented Boston Brahmin. In fact, those "things of various sorts"--numbering, according to one estimate, 26,000 pieces of painting, sculpture, ceramics, and manuscripts--formed the heart of one of the world's greatest museum collections.

As to the Eastern philosophy, he studied and then embraced Buddhism, as did his friend Ernest Fenollosa, A.B. 1874. Bigelow's 1908 Ingersoll Lecture at Harvard explained "Buddhism and Immortality" in scholarly detail, and was later published.

Bigelow was truthful in saying he had no wife or children, but not in denying that he had written books or received honors. Japan awarded him the Imperial Order of the Rising Sun, with the rank of Commander, the highest distinction bestowed in that country on persons not in official life (he wears it in the charcoal portrait opposite, drawn by his friend John Singer Sargent).

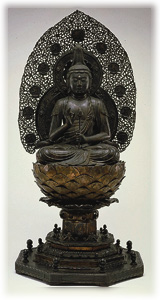

| Below: Three of Bigelow's gifts to the Museum of Fine Arts--Winslow Homer's Woodsman and Fallen Tree, Kobayashi Eitaku's Izanagi Creating the Japanese Islands, and Saichi's Bodhisattva of Compassion Bearing the Lotus |

|

|

|

Bigelow was profoundly affected by the death of his mother when he was three. (His Ingersoll Lecture states that "Maternal love is the source of all human virtues.") His father, the renowned surgeon Henry Jacob Bigelow, was something of a martinet, and young William was evidently something of a rebel: his report card from the Private Latin School in 1865 rated him twenty-second academically in a class of 55, but fifty-fourth in "conduct."

After graduating from Harvard Medical School in 1874, Bigelow went to Europe. He stayed five years, studying in Vienna, Strasbourg, and finally in Paris under Pasteur. He brought back to Boston the new research on bacteria, and established privately one of this country's first laboratories in that field. This displeased his father, who wanted the line of distinguished Bigelow surgeons at Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital to continue. William was duly appointed surgeon to outpatients at the MGH. "Few men," wrote medical historian John F. Fulton, "could have less taste for surgery than the sensitive Bigelow, and it was not long before he gave up all thoughts of practice."

In 1881, believing that the world was moving too fast and that much of life in Boston was ugly, he went to Japan, following Edward S. Morse and Ernest Fenollosa, who were among the first Americans to study Japanese culture. He later called the cruise to Japan the turning point of his life. During his prolonged stay he studied, traveled, and collected the treasures that the Japanese were discarding in their rush to become Westernized.

After returning to Boston in 1889, Bigelow devoted much of his time to the study of art and Asian religions. He also entertained lavishly at his home at 56 Beacon Street, often welcoming such College friends as George and Henry Cabot Lodge, Brooks and Henry Adams, and Theodore Roosevelt, who regularly made Bigelow's home his Boston headquarters. He became an active trustee of the Museum of Fine Arts and continued to collect paintings, often consulting with Isabella Stewart Gardner. Reportedly somewhat reserved in his dealings with the opposite sex, he once wrote to her coyly, in the third person: "She is very attractive." At his favorite spot in America, however, a summer house on tiny Tuckernuck Island, off the shores of Nantucket, he entertained men only, and his guests wore pajamas, or nothing at all, until dinnertime, when formal dress was required. A staff of servants provided food and fine wines; the library contained 3,000 volumes, "spiced with racy French and German magazines," one chronicler reported. Henry Adams described Bigelow's retreat as "a scene of medieval splendor"; George Santayana, A.B. 1886, may have modeled Dr. Peter Alden, the father of the protagonist in The Last Puritan, after Bigelow.

The Boston Evening Transcript, the unofficial gazette of Boston's Brahmins, ran two bold headlines on October 6, 1926. One told of Babe Ruth's still unexcelled feat of hitting three home runs in a World Series game, but the larger headline reported the death of William Sturgis Bigelow. His funeral, at Trinity Church, was conducted by his classmate William Lawrence, the former Episcopal bishop of Massachusetts. His ashes were divided. Half were interred in Mount Auburn Cemetery, which had been envisioned by his grandfather Jacob Bigelow as a spiritually uplifting as well as "hygienic" burial site. But the rest were buried by a Buddhist temple, overlooking Bigelow's favorite lake in Japan.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()