Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

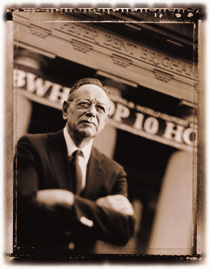

"If no one is exploited in the process, and the child is wanted and loved, there can't be anything wrong with it," says ethicist Kenneth Ryan.

"If no one is exploited in the process, and the child is wanted and loved, there can't be anything wrong with it," says ethicist Kenneth Ryan. |

"As a society, we push the infertile toward ever more elaborate forms of high-tech treatment," writes Elizabeth Bartholet in her book Family Bonds: Adoption and the Politics of Parenting. The Wasserstein public interest professor of law at Harvard Law School, Bartholet was herself a pioneer in pursuing assisted reproduction in its formative years. As a single woman with a son from a previous marriage, she wanted to parent again on her own. She wore what she called her "IVF wedding ring" and pretended she was under 40 during her 10-year battle with infertility in three states. Then, one day in 1985, she realized it was time to move on. That fall she adopted Christopher in Peru, returning two years later to adopt Michael.

Bartholet saw herself as bravely exercising her procreative rights. "But what is an obsession and what's freedom, and when is it what you really want to do?" she asks. Now she sees such a quest as "pushing a woman to obsess more and more about her inability to be the woman she's supposed to be in the classical, traditional sense." Such a choice isn't free but conditioned. "What women and couples would be choosing in a world in which we had different attitudes about the significance of biological parenting and different financial structures, and where you had a constitutional right to adopt the way you have a constitutional right to procreate--I just think there would be significantly different choices being made if it were a more even playing field," she says.

Bartholet is not out to ban IVF, but she does call for a national commission to discuss the social and ethical issues raised by assisted reproduction. "The fact that we're not facing these issues as a society is in itself a major ethical issue," says Bartholet. Instead, we're "letting doctors operate in this vacuum and resolve these issues themselves. They are not facing up to the ethical issues, and they are not the ones who should be resolving them."

The ASRM's ethics committee writes that it "is painfully aware that many issues of critical national concern...are not being addressed by any effective mechanism for the development of sound public policy," and they, too, call for a national commission. Reproductive biologist Mitchell Rein, an assistant professor at the medical school who is chief of ob-gyn and director of women's services at Salem Hospital/North Shore Medical Center, agrees that "a more formal regulatory board might be helpful" for the ethical issues that challenge infertility specialists, "so that as a field we're somewhat unified in our voice and somewhat consistent in our treatment."

Regulation of the infertility industry is not enough for some opponents. The initial feminist reaction to assisted reproduction in the 1970s was very negative, notes Linda Blum, a sociologist and women's studies specialist at the University of New Hampshire who was a 1996-97 Bunting Fellow. The Boston Women's Health Book Collective, creators of the women's health bible of the '70s, still argues strongly against ART in The New Our Bodies, Ourselves. The organization FINRRAGE (Feminist International Network of Resistance to Reproductive and Genetic Engineering) wants to outlaw many forms of the new reproductive technologies completely. They believe that ART is a male-controlled intervention that alienates women from the reproductive process, that commercial surrogacy is a form of slavery and the "sale" of eggs amounts to a "reproductive brothel," that the children produced are then commodities as well--the first step down the slippery slope toward genetic engineering. Ruth Hubbard has long felt that IVF provided experimental biologists with access to human eggs and embryonic development "dressed up as a medical benefit."

Blum, author of a forthcoming book on ideologies of breast-feeding and motherhood, sees a greater diversity of voices now. "There's no 'feminist line,'" she says. "Some women who were infertile--for whatever reason--felt very insulted that their genuine desires to have a biological child were seen as some sort of patriarchal false consciousness."

For Kenneth Ryan, it's an oversimplification to suggest that the mere existence of assisted reproduction is itself coercive--"Being childless is what is coercive." One of the major distinctions between natural and assisted reproduction, he adds, "is that we know in the infertility case that the couple is actively seeking to have a child. In over half the reproduction that occurs normally, the child is conceived without intent--and that's the height of irresponsibility and poses serious ethical problems."

Arthur Dyck, Ph.D. '66, says we should also ask, "How will others be affected by assisted reproduction, and how will I be affected in self-destructive ways?" The professor of population ethics at the Divinity School and the School of Public Health says, "There is such a tendency to make 'autonomy' a moral imperative and to use it as the answer to every difficult question. But choices involving reproductive technologies affect all of us. We are all responsible for the children that are born."

The Vatican, the most powerful institutional opponent of ART, condemns it as dehumanizing. The Instruction on Respect for Human Life in Its Origin and on the Dignity of Procreation (1987) states that ART denies the "language of the body" for the spousal expression of love. The act of sexual intercourse within marriage "unites body and spirit in the bringing into existence of new life. To create new life without sexual intercourse is thus to fail to accord human reproduction its full dignity." The consequences of disembodied procreation are the objectification and commodification of women and children; therefore, it should be illegal.

But Selwyn Oskowitz has seen the other side of such edicts. "A lot of pain and suffering occurs, including guilt and all its ramifications. Patients agonize and are precluded from having a family because they cannot participate in IVF," he says. It's usually uninvolved bystanders who pass these judgments, he adds. "It's the same old story--there are no atheists on a sinking ship. And the converse is true. It's easy to be religious about certain aspects of life when your life's needs are not threatened."

Ryan has witnessed many people undergo IVF despite the disapproval of their faith. "There's this tremendous drive to have a child," he says. He thinks this drive "looks and feels biological" and suspects it is derived from both culture and biology. "But if you've ever seen individuals warm up to a newborn baby, or been on an airplane with a mother and young child, with all of the other passengers eyeing or cooing the child, and the stewardesses wanting to hold the child--for lack of a better term, I'd have to say that gets pretty close to human nature."

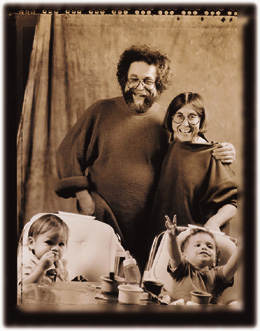

Larry Sager, 56, and Jane Cohen, 52, with their fraternal twin daughters, Mariah and Jemma.

Larry Sager, 56, and Jane Cohen, 52, with their fraternal twin daughters, Mariah and Jemma. |

When all else fails, reproductive technology includes donor sperm and donor eggs in its arsenal. Elizabeth Bartholet calls these methods, together with surrogacy, "technological adoption," because they involve "the production of children designed to be cut off from their genetic forebears." She feels our society is "completely inconsistent and schizophrenic" regarding the significance of the biological link. Although "adoption regulation is premised on the notion that biology is everything," with its focus on the rights of the birth mother (and father), "our tolerance of a free market in the ART realm seems premised on the attitude that biology doesn't matter at all," she says. "Therefore it's OK to induce men to give sperm for money, and have laws set up so that they have no responsibility for the child. Therefore it's perfectly legal, at least so far, for women to be induced to come in and 'sell' their eggs."

The practice of using one man's sperm to rectify another man's infertility is the oldest form of assisted reproduction, going back to the late nineteenth century. In the 1950s and 1960s, universities were the principal repositories of donated sperm. "In the old days, we used to have Harvard medical students come over and donate their sperm and everything was very secretive," Annie Geoghegan recalls. "You probably know some sperm donor children and you don't know that they are--and they may very well not know that they are."

In the 1970s, private, for-profit sperm banks arrived on the scene. Susan Pauker, the medical geneticist, was called by one in California: "How many donations did I think a donor should give to a given geographical area before too many people on the street would look like the donor?" This poses another ethical problem, notes Oskowitz--"where there are children born in the community who may mate unknowingly with their half-siblings." In an area the size of greater Boston, he says, statistical models show that the odds of consanguinity are extremely low for up to 10 children from the same mother or father. However, he adds, "if there were a clinic in Hope, Arkansas, they'd have to be very strict on the number of offspring."

In reality, "ovum donors rarely donate that frequently," says Oskowitz. That's largely because it's much more difficult to donate eggs. "A man can just ejaculate and go on with his day," explains Geoghegan. "A woman who's donating an egg has to go through an IVF cycle, including intramuscular drug injections, daily vaginal ultrasounds, blood tests, and a surgical procedure." Most clinics restrict the number of times a woman may donate eggs to two or three. ASRM is ethically opposed to payment for gametes, recommending compensation only for time, expense, and--for egg donors--risk and inconvenience. That amounts to a generally accepted rate of $35 per semen collection, and $1,500 per egg-retrieval cycle.

Brigham and Women's enlists only "known" egg donors designated by the couples themselves, says Mark Hornstein. "The majority of these tend to be sisters, which is our most common arrangement, or close friends," he says. Other programs, concerned about potential familial problems, may prefer different arrangements. Boston IVF offers an anonymous egg-donor program as well, mostly filled by word-of-mouth recommendations from previous donors. They also advertise in newspapers and elsewhere. Many women who donate for Boston IVF already have children and want to help other people have a family.

Because one-year waiting lists are often the rule for anonymous donation, many couples recruit donors on their own, says Geoghegan. One woman is a Ph.D. candidate at MIT who saw an ad in the Cambridge TAB. "She's smart as can be, needs money, and thought it would be a really cool thing to do," says Geoghegan. Another grad student was recruited by a notice in a Harvard gym--"People think that's a way to get healthy, smart young women," says Geoghegan. "She had to decide that she really wasn't ready to do it. And of course the recipient was heartbroken."

Jane Cohen, 52, and Lawrence Sager, 56, are the parents of one-and-a-half-year-old fraternal twins. Their daughters' names are Jemma Marshall Sager and Mariah Mill Sager, after John Marshall, the famous chief justice, and John Stuart Mill, author of On Liberty and The Subjection of Women. Their nominal choices aren't that surprising, for both parents are professors of law: she specializes in family law and bioethics at Boston University, and his area is constitutional theory at New York University. With six previous children between them--Cohen has a 27-year-old daughter from her first marriage, as well as three stepchildren (aged 38, 36, and 34), and Sager has a daughter, 27, and son, 25-- neither is new to parenting.

Cohen always wanted to have more children, but her second marriage, to a partner who supported this choice, took place relatively late. When she was 42, she and Sager began their endeavor to start a family together. Her ob-gyn of two decades was "very antitechnology" and urged the couple to stick with conventional treatments. They turned to ART only when Cohen was 45 and still not pregnant. They both found it "fascinating to enter this world at an advanced age," says Cohen, and they have since become champions of reproductive technology.

After four miscarriages, it came time to consider IVF with donor eggs. Jemma and Mariah were conceived at Boston IVF with Sager's sperm, then transferred to Cohen's womb at Brigham and Women's. At 49, she was among the first women of that age to be treated in the hospital's IVF program. Brigham and Women's doesn't generally accept women older than 49; Cohen's understanding is that women who exceed this age "may still be accepted on a case-by-case basis."

For Mark Hornstein, women in their forties are "of advanced reproductive age, but they're still of reproductive age." But the California woman who gave birth at 63 is another story, he notes, pointing out that her "life expectancy is 16 years or so. If her husband is the same age, it is statistically unlikely that both parents will survive long enough to see that child into adulthood. I have a problem with that." Linda Blum views this as just another double standard. "When a man in his sixties--or even older--has children, we admire his attainment of a better moral orientation, since he was too career-oriented before," she says. But now that a woman in her sixties has done the same, there's "a blatant cultural revulsion that a woman who's supposed to be all 'dried up' has the audacity to claim this right." Cohen thinks it's unnecessary to focus on the possibility that women in their sixties are going to be flooding fertility clinics. Choosing to have a child with the help of ART--especially in middle age--is, she says, a highly self-selective process.

Cohen considers it much more important to recognize that if having children is a social as well as an individual good, then respecting the values our society shares means that we have to respect this need. "To say, You can change careers, you can change husbands, but you can't change your mind about having children--that empties out one of the great promises of American life, which is that you not only get to choose how to live your life, but you get to make renewed choices if you make mistakes," she says.

Insurance coverage (or the lack of it) is the principal way that society proffers or withholds its support for those who suffer from infertility. Massachusetts is one of only 13 states that mandate insurance coverage for treatment. Surprisingly, President Clinton's national health plan proposal excluded infertility coverage, even though Chelsea Clinton was a "Pergonal baby." Reproductive biologist Mitchell Rein says, "I absolutely believe that people with infertility have just as much right to be treated as patients with kidney failure."

Cohen also envisions a new "vanguard feminism" where "the capacious arms of feminism wrap themselves around the possibility that women get to choose to have, as well as not to have, children." When she teaches about ART and the relevant legal issues, some young women appreciate that "this technology will create great relief later in life, will allow them to sort out career and relationship and then children--will allow them to buy time," she says. Although freezing sperm and embryos is commonly practiced, it will be the "dawn of a new consciousness" when eggs can be "frozen and put on the shelf," she says. When young women can store their eggs until the right time--"That will change people's lives," she says.

Elizabeth Ginsburg has in fact proposed an ovum freezing protocol at Brigham and Women's, for young women with malignancies who will undergo chemotherapy. There have been only three or four pregnancies from frozen eggs reported internationally, "but as the protocols get better, I think we will find fewer and fewer chromosomally abnormal eggs after freezing," she says. "The problem is that once you have a successful therapy, you don't really have control over who offers it," she adds. She worries that "women might want to freeze their eggs in case they don't meet anyone when they're young, to stave off infertility." She disagrees with this solution. "We already see couples coming in for IVF because it's not a convenient time for them to have kids. But we won't do it because they don't have an infertility diagnosis, and because there are significant risks for these procedures," she says. "Should you use these hi-tech infertility treatments for convenience? Is it just a commodity that you can buy if you have the money? Right now we're uncomfortable with that and we're not offering."

But Cohen takes issue with Ginsburg's argument. "What some people would describe as convenience, I would describe as exactly what society should hope for--the ultimate social dream--creating a technological and social environment in which people have children only if they're ready and when they're ready and not before. It isn't about 'convenience,' it's about social and psychological and financial development," she argues. "Infertility can strike women at any age--the likelihood simply increases with age. Medical interventionism is not the only needed response to the work/family conflicts that pursue women, but it is one of many valuable social options."

Elizabeth Bartholet, on the other hand, does not regard high-tech infertility interventions as a great way to deal with work/family conflict. "A lot of women are infertile because they postpone pregnancy, and there's a lot of pressure on women--particularly professional women--to do that," she says. But instead of assisted reproduction, "what we need is a way of dealing with work/family conflict that enables women to work, earn money, have the power that goes with it, but also get pregnant and have families early enough that they don't have to deal with infertility," she says. "That's what we allow men to do, but we set up the world for women so that they've got to choose--and often choose at the cost of their fertility."

Speaking from experience, Linda Blum, who had her son Saul [Tobin] at 32, recalls that some of her colleagues and friends "thought that was shocking--so early." Her husband, Roger Tobin '78, is the same age she is, and his academic colleagues said, "Couldn't you have waited until you had tenure?" He would answer, "I wasn't aware I was supposed to have married a younger woman."

When Janet Taft was a nurse midwife--delivering 230 babies during her career--she had no idea she would later face difficulties bearing her own children. She and her husband, Renny Merritt, became investment bankers, but Wall Street's pressures didn't help their fertility. They began conventional treatments when Taft was 35. After three years, deciding that having a family was more important than "making a pile of money," they left New York for Massachusetts and began working with Selwyn Oskowitz and ART. They went on to have a total of three miscarriages, becoming more resigned with each one.

They were about to run ads for an open adoption when another pregnancy test came back positive. They didn't expect much, but the first ultrasound found a strong fetal heartbeat and the second found two. "It was divine intervention," Merritt likes to say, for this was a spontaneous conception. Their identical twins, Breck and Riley, were born in 1991 when Taft was almost 41. They knew even then that they wanted another child, but at 42, Taft's chances of achieving pregnancy through IVF were only 4 to 6 percent; with the help of an egg donor, they would triple. While they continued to investigate adoption, they signed onto Boston IVF's anonymous egg-donor list.

When their names came up, it appealed to Taft that the donor "did this on her own." They never met, but Taft's and the donor's cycles were synchronized through fertility drugs. The donor's eggs were "harvested," then four were fertilized in vitro with Merritt's sperm and transferred to Taft's uterus. "Three of the four took!" she says. "If I had known how readily it can work with younger eggs, I think I would have done it sooner." During the twin pregnancy (one fetus never developed a heartbeat), Taft marveled at the irony of "capping off seven cumulative years of infertility as a 'gestational surrogate.'"

Now they had to decide what to tell their family and friends. Boston IVF recommends "the value of privacy but not secrecy," says Oskowitz. Taft and Merritt took this one step further, believing "it is healthiest to be born into an atmosphere of complete openness. And if we help even one person by being open, then it's worth it. If there is a stigma, we're not going to contribute to it. We're proud of what we've done, and we want everyone to know how we did complete" what they're fond of calling "our industrial strength family."

When Sawyer and Whittaker were born in 1995, when Taft was 44, she remembers feeling, "They're from me but not of me. How do I reconcile this? And yet it seemed like there wasn't any reconciling to do." At about six weeks, "A sense of peace came over me," she says. "I was at peace about the egg donor. How they are like her, how like my husband, what was the significance of this--it all simply evaporated."

Taft and Merritt want their sons to learn about Whittaker and Sawyer's origins with the same instinctive calm. "We don't want to make a big deal about 'telling' them," she says. "It's a fact of their birth. The egg-donor nature of their beginnings is key to who they are, it's central. But in their lives and within our family, it's minimal, it barely matters at all. It's just part of the story of how they came to this family."

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()