Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

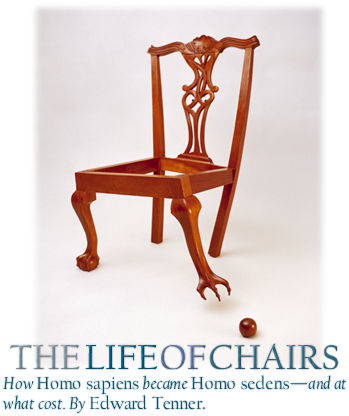

Jake Cress's Ball and Claw Chair, recently displayed at the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery, is a quadruped with ergonomic problems of its own. Photograph by Martin Church |

The Norwegian chair manufacturer T.M. Grimsrud, president and CEO of the prestigious company Hag A.S.A., once confessed in the journal Ergonomics that "humans were not created to sit; humans were created to walk, stand, jog, run, hunt, fish, and to be in motion; when they wanted to rest, they laid down on the ground." This statement is probably not valid anthropology; nearly 40 years ago, Gordon Hewes identified dozens of sitting positions around the world in a Scientific American article that unfortunately remains the main summary of its subject. But perhaps this variety only reinforces the first part of Grimsrud's statement. If there were a natural way to sit, we would not have so many chair designs with radically different principles, from kneeling to reclining. No wonder artists almost invariably portray Adam and Eve standing in paradise. Before the fall, we were indeed upright. Standing is in many ways a healthier position than sitting, especially sitting in chairs, which tend to rotate the pelvis forward and increase the load on the spinal column by about 30 percent. Prolonged sitting at work has been shown to shrink the spine and swell the feet temporarily. No matter. The more ills Western-born science traces to the Western- (or more exactly Near Eastern- and Mediterranean-) born chair, the more ubiquitous it has become worldwide. In the German historian Hajo Eickhoff's expression, Homo sapiens has become Homo sedens.

Seating defies linear chronology. Materials and doctrines change, but the human body and certain basic forms remain. Reclining, for example, connects the ancient Athenian symposiast, the Viennese analysand, and the San Jose programmer. Even the ubiquitous folding director's chair echoes the field seating of Roman officers. Sometimes analysis must follow chairs as they move through time and space, for the chair itself sits at an often dangerous intersection of the cultural and the biological. It can be seen from three sides: as a reflection of humanity; as one of humanity's self-imposed constraints; and, most recently, as the site of physical consequences of an information society.