Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

![]()

![]()

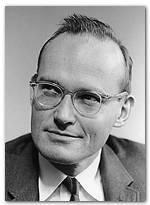

The late McGeorge Bundy, JF '48, LL.D. '61, who died on September 16, was a 34-year-old associate professor of history when he became dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences in 1953. He left Harvard in 1961 to join the Kennedy, and later the Johnson, administrations; in 1966 he became president of the Ford Foundation. In the summer of 1970, following convulsions on campuses nationwide, Daedalus published an issue on "Rights and Responsibilities: The University's Dilemma" to which Bundy contributed an essay entitled "Were Those the Days?" that discussed Harvard in the 1950s. Some excerpts:

Harvard never took a gift or endowment that was unwanted by the affected part of the faculty, and Harvard gave to no rich man the right to say what Harvard should not do. Generous rich men could and

Bundy in 1960 |

§

The departments in our day were clearly indispensable; much more often than not they were agents of honorable labor and conscientious choice. Yet when a department went on the defensive, it could do very great damage both to itself and to the rest of the university...It was a bad sign, for example, when a department was resistant to the suggestion that it might consider some very remarkable man from far away. There might in fact be good reasons not to go after him, but a strong department would state them confidently, not fearfully. It was also a bad sign when a department resisted grade A men in new subjects while doggedly proposing grade B men in old subjects--for here the shape of the field was determining the quality of our work, when the quality of our work should have been helping to reshape the field.

§

To make one's student run the course one has run oneself is only human, but it can be a most arid way of teaching.

§

Turning back to the fifties, I will assert that we were right on one absolutely vital point: we knew what the university was for: learning. The university is for learning--not for politics, not for growing up, not even for virtue, except as these things cut in and out of learning, and except also as they are necessary elements of all good human activity. The university is for learning as an airplane is for flying. This is its elemental and defining purpose. There is both affirmative and negative reason for this purpose: no other institution has this mission, and no other mission justifies the university.