Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

| Lust for Books | The Micro-Menace of Biofilm |

| Oklahoma City: A Remembrance | Tighter, Safer Neighborhoods |

| "my home, ill, sick" | E-mail and Web Information |

|

Karl S. Guthke teaches a freshman seminar on last words--dying utterances-- and is the author of Last Words: Variations on a Theme in Cultural History. In an article in a festschrift about European literature to appear this fall, he harkens to "Last Words in Detective Fiction." That the Francke professor of German art and culture should have a firm grip on this literary genre testifies to his innocence of academic nationalism; as he acknowledges, "G.B. Shaw had a point when he remarked that Germans are not good at two things, revolutions and detective stories."

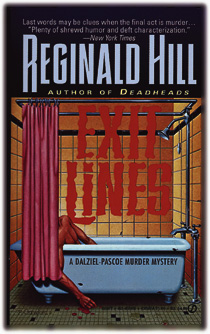

Last words of varying scrutability have been used as clues in detective fiction--from Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841) and Arthur Conan Doyle's A Study in Scarlet (1887), where they are clues in earnest, to Reginald Hill's Exit Lines (1984), which spoofs them. The last words "my home, ill, sick"--pretty mysterious--are from Patricia Moyes's Murder Fantastical (1967) and "turn out to have really been 'my Homer, Iliad, [Book] six'--where the crucial secret message is then indeed found," writes Guthke.

The use by scribblers of last words as clues is so tired a trick that Guthke suggests "maybe last words should therefore be included in those lists of forbidden, hackneyed devices or props that theorists have been outlawing for decades ever since Father (!) Ronald A. Knox [translator of the Bible and mystery writer] (1924) and [creator of Philo Vance] S.S. Van Dine (1928) or the decalogue of the Detection Club Oath (1932). These lists ban motifs such as unknown and untraceable poisons, more than one secret passage, the wrong brand cigarette butt, identical twins or doubles, Asians, servants as killers, forged fingerprints, the dog that did not bark, supernatural agencies. Some authorities would include love, but last words are not included in anybody's list of contraband."

What accounts for this? First, last words often enjoy the status of clues in actual police work. Guthke recalls the real-death 1994 stabbing in Provence of Mme. Marchal, widow of a spark-plug magnate, and the perplexing (because ungrammatical) message written in the victim's blood on the cellar door, "Omar m'a tuer." Second, last words have special legal standing. They "are an exception to the procedural rule which excludes hearsay as evidence in criminal cases....In Anglo-Saxon countries, at any rate, a dying declaration enjoys a special evidential status, vastly superior to in vino veritas....A dying person is not presumed to lie--'Nemo moriturus praesumitur mentiri,' as the maxim of common law has it--the underlying assumption being that there is no earthly motive for telling anything but the truth as the dying person will soon face the judgment of his Maker, who will inflict retribution on those who die with a lie on their lips. (Law courts today are becoming aware, of course, of just how questionable, how ideologically biased, this assumption is in multicultural social contexts.)

"This privileged status of last words in the media's crime and courtroom reporting as well as in legal thought," in Guthke's judgment, "almost predestines them to be a privileged motif" in detective stories as well.

~ Christopher Reed

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()