Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Please note that, where applicable, links have been provided to original texts which these letters address. Also, your thoughts may be sent via the online Letters to the Editor section.

NEXT, VISIBLE MUSIC

Like many others I am sure, I was much struck by Felice Frankel's photographs in your cover article, "Phenomenal Surfaces," by Frankel and George M. Whitesides (July-August, page 41).

You report the serendipitous meeting and subsequent collaboration of Frankel, at the time a photographer of landscapes who came to Harvard as a Loeb Fellow, and Whitesides, a Harvard chemist. With serendipity in mind, I have written to Frankel to say that should she ever be tempted to move from images of physical matter to spectrographs of musical sound, I would be delighted to meet her. Musical spectrographs when they appear in a color display are especially striking. The color ranges from yellow to violet, corresponding to the intensity of each spectral line. My book New Images of Musical Sound (Harvard University Press) has a number of black-and-white images. The look of the sound of music could be spectacular in the hands of someone with Frankel's skills.

Robert Cogan

Chair of graduate theoretical studies and professor of composition, New England Conservatory

Boston

ZIONISM, FEMINISM, AND A BLESSING

No sensible or feeling person can take exception to Professor Ruth Wisse's campaign to end the centuries-old Jewish culture of victimhood ("'Mame-loshn' at Harvard," July-August, page 32). But she seems unconcerned that the Zionist movement--the process by which she sees the Jews restoring their manhood--has created an injustice for the Palestinians, who bear no responsibility for the horrors perpetrated on the Jews in Europe. Yet it is their land that is being taken away to make way for Zionism. She opposes the Oslo accords because they hold out the promise of the return of a small portion of the land to the people who, on the eve of World War I, and before the British-protected Jewish immigration of the twenties and thirties, constituted 88 percent of the population of Palestine. And she deplores the "scandal" of Arab resistance. What would she have--that the Palestinians should become the schlemiels of the present age? Wisse's preoccupation with Jewish redemption, and disregard for the effect it may have on anyone else, is shallow and repugnant, and it goes a long way toward placing her view of what Zionism means on the same moral plane as Nazism.

Michael Sterner '51

Washington, D.C.

Wisse is shocked at the "scandal of Arab rejectionism," 50 years after Israel's birth. Having been driven by Israeli terror from their homeland, tortured by the thousands, and seen their land and water confiscated for the benefit of Jewish settlers, Palestinians are simply responding in self-defense, refusing to accept exile and subjugation. If Zionists could return home after 2,000 years, why should Palestinian Christians and Muslims resign themselves to exile after 10 or even 50 years?

Wisse says for Jews to overlook the "outrage" of Arab refusal to accept Israel is "an affront not only to Jewish life but to any moral life worth living." Yet Jewish life is based on the pursuit of justice, and the expropriation of Palestinian lands is, in the words of Haim Cohen, a former member of Israel's High Court of Justice, "stealing in one of the ugliest ways."

The way to fight anti-Semitism is not to turn Jews from victims into victimizers, but to work for the rule of law on the international scene and human rights within every nation, including Israel. Unfortunately, nationalists, including most Zionists, refuse to treat outsiders as equals. Wisse's anti-Arab positions, and her attacks on Jews who believe non-Jews deserve the same rights as Jews in a "Jewish" state, reflect an inability to empathize or even understand the Palestinian experience under Zionism.

Edmund R. Hanauer

Executive director

Search for Justice and Equality in Palestine/Israel

Framingham, Mass.

Nice to see a Harvard professor of Yiddish, a woman no less. But it seems to me that Wisse is another protected North American Jew throwing matches at the powder keg that is Israel. Don't the Palestinians have a point? As a people who long for a land of our own, Jews should be able to understand the anger and despair of those who have lost their land to us. Wisse should leave the Ivory Tower and walk her talk, go live among Israel's militants who literally thank God they are not women and actually believe they have the right to decide who is a Jew. Let Harvard University join the chorus of voices for peace, not war, in the Middle East.

Jane Birnbaum '77

Los Angeles

Your report on Wisse is magnificent--and so is she. Her criticism of ultra-feminism and its "culture of victimhood" is particularly to the point--"By defining relations between men and women in terms of power and competition, instead of reciprocity and cooperation, the [women's] movement tore apart the most basic and fragile contract in human society, the unit from which all other social institutions draw their strength"--marriage.

Wisse's statement, and its detailed corroboration by Christina Hoff Sommers's Who Stole Feminism? How Women Have Betrayed Women, demonstrate how feminism is indeed helping to destroy marriage--which is already in enough trouble. Full reappraisal of that movement--including women's studies programs throughout America--is therefore vitally and immediately necessary.

Nathaniel S. Lehrman '42, M.D.

Roslyn, N.Y.

I was very much moved to read "'Mame-loshn' at Harvard," all nine pages of it. As an undergraduate, I lived through President A. Lawrence Lowell's project to strictly limit Jewish enrollment in the College. At that time, the only avowed Jew on the faculty was Harry Wolfson.

Now I witness a Harvard that has been thoroughly cleansed and Judaized. My reaction on reading this account was to recite the ancient Hebrew blessing: Blessed art thou, oh Lord, our God, King of the universe, who has kept us in life and sustained us, and caused us to reach this (happy) occasion.

Rabbi Abram Vossen Goodman '24

Cedarhurst, N.Y.

THE HARVARD WARS

I differ with your reviewer James Glassman '69 that Roger Rosenblatt's Coming Apart will do fine as a guide to the takeover of University Hall in 1969 ("The Browser," May-June, page 24). Like Rosenblatt, I was there as a junior faculty member and member of Dunster House, but otherwise we might have been on different planets. Among the major flaws in his account were:

1. An extraordinary insensitivity or ignorance of the emotional strength of the antiwar feeling among most of the students and many of the younger faculty. As Rosenblatt admits, he couldn't imagine anyone with less knowledge, much less passion, about Vietnam than himself.

2. Perhaps because his role in throwing out student protestors may have led to his becoming master of Dunster House and a candidate for the presidency of Harvard, Rosenblatt didn't notice that the careers of a number of younger faculty supporters of the strike were affected by retaliatory actions of the administration. Jack Stauder '62, a Soc Rel instructor who was in University Hall when the police came, had his appointment terminated prematurely in spite of support from his department. A group of economics department faculty did not receive tenure. Assistant professor Chester Hartman '57, Ph.D. '67, of the city planning department--who was able to refute, at the open Stadium meeting, President Pusey's denials of Harvard's expansion into working-class neighborhoods--was denied reappointment, the letter from his chair citing his "lessened loyalty to the [Design] School and University."

3. An apparent total lack of interest in the fact that, whereas Harvard as an institution could hardly be directly blamed for the war, not a few of its faculty were so heavily complicit that had there been a war-crimes trial, they would have been suitable defendants. My own chairman, Richard Herrnstein, later of Bell Curve fame, did secret work for the military on training pigeons to recognize Viet Cong and radio their positions. (Since secret work was forbidden on Harvard grounds, he rented space in Cambridge to carry it out. See Science, 1964, 146:549).

4. Apparent ignorance that there actually was a third faculty caucus--the radical caucus led by Hilary Putnam, then and now one of the world's most distinguished philosophers and logicians. Some of Hilary's ideas may have been a bit wild, but typical of the gap between Rosenblatt's and my perceptions of the world is that he saw Hilary as wild-looking (page 114), whereas I saw him as always sartorially and tonsorially elegant, even when he was trying (and failing) to look working class.

Charles Gross '57

Visiting lecturer, assistant professor,

then lecturer, 1963-1970

Professor of psychology, Princeton University

Princeton, N.J.

STEROIDS AND ASTHMA

John Lauerman's "Attacking Asthma" (July-August, page 18) described many significant facets of the disease in an engaging style. In particular, it emphasized our new understanding of the importance of the early initiation of anti-inflammatory drugs to achieve effective remission of symptoms.

However, the author neglected a critical point about the use of steroids, the principal class of anti-inflammatories used for asthma. Not only can they be delivered to the bronchial passages by inhalation aerosols, but this is the recommended mode of delivery to reduce the risk of steroid side effects. Steroids in pill form are recommended only when asthma cannot be controlled by inhaled preparations.

The suggestion that asthma patients are started directly on oral steroids when modest bronchodilator therapy is insufficient to control wheezing is patently incorrect. I suspect you have learned this from other readers familiar with the standard, stepwise therapeutic interventions recommended for asthma.

Stephen Goldfinger, M.D.

Boston

John Lauerman replies: dr. goldfinger correctly points out that inhaled steroids are a commonly used, usually side effect-free therapy for asthma. However, Dr. Albert Sheffer, director of the allergy section at Brigham and Women's Hospital, says it is consistent with the stepwise guidelines to progress directly from bronchodilator therapy to oral steroid treatment to reverse severe symptoms in otherwise mild asthma patients. Concomitant inhaled steroids can be used and continued after oral steroid therapy is completed and symptoms are controlled.

PHILATELIC ADVISORY

PHILATELIC ADVISORY

The caption under the picture of the new stamp honoring the Marshall Plan (July-August, page 51) is incomplete. It states that the three stamps of special interest to Harvard depicted George Marshall, "founder" John Harvard, and faculty member Alice Hamilton. However, two other prominent Harvard faculty members have also appeared on stamps in recent years, namely Paul Dudley White and Harvey Cushing. Moreover, a stamp depicting former Harvard president Charles Eliot was issued in 1940.

The caption also implies that the three stamps mentioned were commemoratives. In fact, only the Marshall Plan stamp is a commemorative stamp (issued to honor a specific event, available in post offices for a relatively short time, now usually large-format in design, and corresponding to the first-class letter rate), whereas the other two stamps were definitive stamps (issued in various denominations to provide regular postage, available in post offices for prolonged periods of time, usually small-format). Unfortunately, the 56-cent John Harvard stamp, though a definitive, was available for only a relatively short time, since the rapid rise in postal rates rendered the 56-cent denomination obsolete (it originally corresponded to the rate for three ounces of first-class mail). It is somewhat sad to see that even so many years after his death, John Harvard can still be a casualty of inflation.

Allan R. Glass '67, M.D. '71

Bethesda, Md.

You say that the Marshall Plan stamp was the third commemorative of special interest to Harvard. Two earlier ones were celebrated in Harvard Yard in 1940. James A. Farley was on hand to honor President Eliot. Those of us in the Harvard Stamp Club (which dissolved in World War II) enjoyed the March 28 ceremony, and the one five weeks earlier for poet and professor James Russell Lowell.

These two stamp ceremonies were important in mending fences between "that Man in the White House," Franklin D. Roosevelt, and his alma mater.

Malcolm M. Ferguson '43

Concord, Mass.

TAKING ON TENURE

Professor Richard Chait is dead wrong about tenure ("Rethinking Tenure," July-August, page 30) when he writes, "Unfortunately...too many faculty playbooks have one entry under the tenure tab--the American Association of University Professors' recommended policy." Too few have such an entry. And that "the times have changed since 1915, when the AAUP was established," makes the AAUP policy more necessary, not less.

I assure Chait and your readers that without the AAUP policy and its attendant standards, academic life and academic freedom would at many, if not most, colleges and universities be much more precarious than it is.

Tenure is the normal status of college and university faculty--as it is for judges and priests, and for the same reason: to guarantee disinterested judgment and professional integrity. The other normal status is probationary: most institutions that recognize tenure agree with the AAUP that six years is the maximum length of probationary status.

Chait and many college and university administrations accuse the AAUP tenure policy of constricting institutional growth and change. This is not the case. What the policy does require is that an institution's planning "to reallocate resources and enhance programmatic flexibility" and "to eliminate 'deadwood' in the faculty" is primarily the right and responsibility of the faculty. Tenure does not prevent incompetent faculty from being dismissed, as long as the dismissal conforms to appropriate procedures (hearings, finding of facts, right of appeal, and so forth).

The real reason for what Chait calls the "gridlocked debate" over tenure is that administrations tend not to recognize the faculty's right and responsibility for running themselves and their programs. Their mindset is corporate, not collegial. Chait may be a professor; but as a "professor of higher education," he speaks only for administrators.

Blair F. Bigelow '60

Cambridge

As a retired professor with half a century in academia, I was much heartened by Chait's sensible if controversial article. I think his analysis is right on and am delighted to learn of the "New Pathways" project of which he is co-leader. All concerned with the college and university world urgently need help in getting beyond rigid posturing.

His brief, pithy article does not mention one heavy cost of the tenure system as it is currently administered. The up-or-out decision on tenure comes at about age 30 to 35, when assistant professors have typically incurred heavy family responsibilities with minimal resources. It is a horrendous time to rebuild a whole career--as failed tenure entails now that the post-war decades of rapid expansion and generous financing are over. No longer can Harvard's rejects count on going to top state universities, or rejects from these on filtering down to lesser colleges. At all levels, recruiters are likely to prefer hopeful new Ph.D.s to embittered failures in the tenure race. Understanding that this is the case casts a pall on all young faculty, impairing the creative scholarship and teaching of those who succeed in the system as well as hurting those who fail. American academia can surely do better, though change will be difficult and painful.

M. Brewster Smith, Ph.D. '47

University of California at Santa Cruz

Santa Cruz, Calif.

Chait proposes that "more professors [be afforded] the occasion to accept voluntarily a term contract in return for a higher salary...or more frequent sabbaticals" or that they be given a chance "to serve indefinitely as senior lecturers or clinical educators." What his proposals overlook is the growing trend toward academic "migrant labor"--the use of adjunct faculty (described in the New York Times of June 29, 1997, page 14), who "earn about $1,500 a course, with no benefits or pension. With such miserly pay, many of them hold several jobs at once, and spend the week rushing from one campus to the next."

Try, for example, teaching a full lecture course to 45 students with no teaching assistance, three times a week, and clearing $500 a month after taxes. How many courses must one teach--year round, with no time to invest in scholarship and writing--simply to get by? How long should one's passion for teaching and scholarship survive under such constraints?

According to the Times, "Almost half of four-year faculty and 65 percent of two-year faculty are part-timers." This is the true shadow side of the changing world of faculty hiring. Contract positions may, indeed, be one way to transform the structure of American academia, but if those who seek to do so fail to address this "invisible faculty" system, they will see more and more gifted scholars and teachers forced to leave their fields not for lack of love, but out of despair.

Linda L. Barnes, M.T.S. '83, Ph.D. '96

Cambridge

Chait's recommendations for alternatives to tenure are shortsighted, and his villains are strawmen (or strawpersons). The real villains of the piece are the pusillanimous campus leaders (perhaps an oxymoron) who refuse to stand up for a way of working life that is the sine qua non for creative productivity. Chait ignores the most fundamental prerequisite of work motivation--a reward system and associated culture that supports long-term commitment to the institution and the taking of risks. All of Chait's recommendations for contracts would replace trust--which is central to good working conditions and supportive of strong work motivation--with a bureaucracy that breeds mistrust and negative sanctions for contract violations. Neither the stick, nor the carrot, nor both in tandem, have been shown to work, save perhaps in the military or civil service--and probably not even there in the long run.

The demands for greater efficiency in colleges and universities suffer from what Gordon Allport called a "rare zero" judgment--blaming all for the sins of a few. Deadwood does occur--but rarely. The tenure baby that has so successfully supported higher education for so many years is too precious to throw out with the bathwater in a spurious fit of housecleaning.

James L. Bess, M.B.A. '60

Professor of higher education,

New York University

New York City

DAVID MCCORD

Reading the account of the life and passing of David McCord in your July-August issue ("The Alumni," page 76) prompts me to write. McCord and I shared a first and last name, and an alma mater. With his sly wit, perhaps McCord, now ensconced in the celestial Cambridge, will enjoy this bit of sophomoric (and bordering on in-bad-taste) doggerel I composed immediately after reading the abovementioned article:

So sad

I had

To die.

Oh my.

Suddenly,

Glee!

Whew!

It wasn't really

Me!

David Elton McCord, J.D. '78

Des Moines

THE CONVERSATION ON RACE

We were of course honored to see our book, America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible reviewed in "The Browser" (July-August, page 21), but we wish reviewer Christopher Edley Jr. had revealed something of what the book was about. In addition, we were a bit shocked that the magazine should have assigned the book to someone whose own work we sharply criticize at length, and that it should have published the review more than two months before the book's actual publication date.

Edley's review would have readers think the work was a discussion of affirmative action. In fact, it is a comprehensive analysis of the changing status of African Americans and the changing state of race relations since World War II. Thus, after six historical chapters taking the story through the 1960s, we explore the rise of the black middle class, the story of increasing residential integration and black suburbanization, the breakdown of the black family, the persistence of black poverty, the Supreme Court's rulings in job discrimination cases, the continuing racial gap in levels of academic performance, and other such topics. Does Professor Edley have nothing to say about any race-related subject other than affirmative action?

Edley concedes that his command of history is insufficient to allow him to judge "any subtle historiographical contributions" that our book might make, and asserts that the detailed historical analysis we offer is of no consequence for readers interested in contemporary issues. "The disagreement about civil rights today concerns not the historical record, but the needed pace of progress now." This claim strikes us as embarrassingly naive and simplistic. What we have to say about black progress in the 1940-1970 period has vital implications for the assessment of the effects of the affirmative-action policies pursued since then. The issue of race is deeply rooted in our history, and our interpretations of that history profoundly influence the stance we take on civil-rights matters today.

He has little taste for either history or facts. One of the most distinctive features of the book is that it provides the reader with no fewer than 76 tables that include often unpublished or difficult-to-find economic, social, and demographic data. Even our most severe critics should find them extremely useful. If you doubt the gloss we put on these statistics, we have supplied them for you to contemplate and interpret differently. Edley fails to mention this, perhaps because it would contradict his claim that we are out to score points rather than to explore difficult issues in all their complexity.

Edley has the courtesy to call one of us a scholar, but labels the other (Abigail Thernstrom) a "conservative policy provocateur." In fact, her previous book, published by Harvard University Press, won four academic awards, including one from the American Bar Association. We would have thought that such mudslinging would not meet the standards of Harvard Magazine. Indeed, the charge is slightly amusing when it comes from a member of the faculty best known for his political activity. Edley was a key player in the Dukakis presidential campaign, and is today President Clinton's point man on affirmative action. He is thus primarily a policy advocate, not a scholar--as his politically driven review makes evident.

We can only guess at the reason for the odd timing of the review--published long before your readers could check the book out themselves. The publication date is September 10. Perhaps Edley wanted to have the first word on the work. If so, he missed his chance. The general rule that reviews are to be held until the approximate date of publication does not apply to journals for the book trade. Harvard Magazine reached us at the same time as the July 1 issue of Kirkus Reviews, a periodical for librarians and book stores. Your readers may wish to know that the anonymous reviewer there had a radically different view of our achievement. "In a debate long on pat answers and resentful rhetoric," the reviewer said, "[the Thernstroms] introduce often absent elements of thoroughness and dispassion." This "vast historical and sociological survey of the past 50 years of race relations, recalling Gunnar Myrdal's 1944 landmark, An American Dilemma," Kirkus Reviews concluded, is "likely to be seen as the benchmark scholarly study of America's current anguish over the race question."

Intellectuals across the political spectrum--from Professor Henry Louis Gates to Shelby Steele to William Bennett--have given our book a wonderful thumbs- up. If Edley is on a search for "kernels of truth"--as he claims--perhaps the massive amount of data we provide would be a good starting place. For even the most partisan of "policy provocateurs," our mountain of factual information, drawn from such reliable sources as the U.S. Census, should provide food for considerable thought. Surely we can agree that race remains our most important domestic issue; and as such, it requires a nuanced touch, a measure of integrity, that Edley could not bring to his review.

Stephan Thernstrom, Ph.D. '62

Winthrop professor of history

Cambridge

Abigail Thernstrom, Ph.D. '75

Senior fellow, The Manhattan Institute

New York City

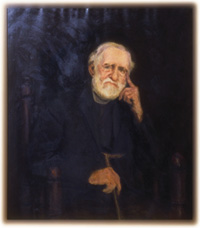

Austin Kingsley Jones. A janitor hired by Harvard in 1858, he rang the bell in Harvard Hall for 50 years.Photograph by Flint Born

Austin Kingsley Jones. A janitor hired by Harvard in 1858, he rang the bell in Harvard Hall for 50 years.Photograph by Flint Born |

OLD JONES, THE BELLRINGER

My wife, Marion, and I were delighted to read about "Old Jones" in the May-June issue ("Treasure," page 88). In the early 1950s, when I was in the dean's office at the Business School, Marion discovered a rolled up oil painting in a Cambridge antique shop. The proprietor described it as a portrait of "a Harvard bell ringer who summoned students to chapel." We have since learned that it was painted by Pietro Pezzati, who also did the portrait of Ralph Lowell (on page 45 in the May-June issue), and of Henry Lee Higginson, founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which graces the Massachusetts Avenue entry to Symphony Hall. Our portrait of "Old Jones" invariably draws comments from visitors to our home.

Vernon R. Alden, M.B.A. '50

Brookline, Mass.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()