Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

Zumreta

Mustafic sits in the wreckage of her home. AP PHOTO/ALMIR ARNAUT Zumreta

Mustafic sits in the wreckage of her home. AP PHOTO/ALMIR ARNAUT |

His tunic is torn, and the blood is beginning to flow. He stares forward with vacant and uncomprehending eyes. Eighty-four years after his first assassination, Archduke Franz Ferdinand is dying again in Sarajevo. Or so the new Sarajevo City Museum would have the visitor imagine. A ghastly mannequin of the archduke in his death throes is the most dramatic piece in the museum's collection.

With its entrance only feet from the street corner on which Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip fired his pistol in June 1914, the museum is well situated to snare a visitor to the city. It rarely takes the newcomer long, after all, to seek out the corner where it all began.

When I first arrived in Sarajevo in June 1996, six months after the latest war had ended, Princip Corner was more conspicuous than it is today. A wall plaque gravely proclaimed the significance of the spot, and on the pavement below, two footprints were embedded in the sidewalk. Today, the plaque is gone. The footprints, too, have disappeared; discolored pavement is the only clue that they were there. Princip is no longer the man he used to be in Sarajevo--Serbs firing at passersby do not enjoy a good reputation here these days.

Frowned upon, too, in Sarajevo are the Serbs who left the city in the early days of the war. Many city residents tell the same tale. In early April 1992, as roadblocks were going up and as artillery appeared on the hills overlooking the city, many Serb friends and neighbors quietly departed. Some said they were leaving just for a few days; most never came back. Meanwhile, the city began more than three years of agony. As they relate these stories, Sarajevans cannot hide their bitterness. They were betrayed.

The ideal of a multiethnic Bosnia was betrayed as well. The war left the country in ethnically clean fragments. Only now, more than two years after the peace, are people beginning to return home. It is not an easy process. Bosnia today is a country on the edge. A very real history of tolerance is struggling to overcome both fresh wounds of war and injustices dredged up from centuries past.

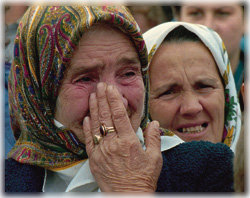

A

Bosnian Muslim cries during a 1996 demonstration for the return to Bosnia

of the Serb-held city of Brcko. AP PHOTO/ VADIM GHIRDA A

Bosnian Muslim cries during a 1996 demonstration for the return to Bosnia

of the Serb-held city of Brcko. AP PHOTO/ VADIM GHIRDA |

In the serb-controlled town of Brcko, I meet a young Serb woman who left Sarajevo in those early days of the war. She had no choice, she says. Her parents insisted that she leave. She has returned to Sarajevo only once, earlier this year. Her old friends were cordial enough, but toward the end of her visit, a friend pulled her aside. It would be better, he said, if she didn't come back.

As we walk the streets of the river-port town, we pass a fading poster of Radovan Karadzic, indicted war criminal and still a hero to many Serbs in Brcko, which was cleansed of its non-Serb inhabitants a few weeks after Sarajevo absorbed its first grenade blasts. Hundreds were tortured or killed and thousands fled. Six years later, some of Brcko's survivors are still struggling to get back home. Many pre-war residents live only a few miles away, often in cramped temporary housing. But the Serbs in the town--almost 10,000 of whom are from Sarajevo--show little sign of yielding.

A Croatian flag flaps over the old fortress in the central Bosnian town of Jajce. The fortress, home to Bosnia's me- dieval kings, held out against the invading Ottoman Turks for decades after the rest of Bosnia fell in the fifteenth century. Centuries later, in the thick of the Second World War, Marshal Tito took up residence at the foot of the fortress and summoned delegates from all over Yugoslavia to craft a new state, one that would put the "nationalities problem" in the past. He had much success: Jajce stood for 45 years as a prosperous, multiethnic town in the center of Bosnia in the center of Yugoslavia. Then, as his creation crumbled, Jajce became an object for the new nationalist armies traversing the country. The town fell to Serb besiegers in 1992; three years later, in the closing months of the war, Croat forces took control.

In the shadow of the fortress, an elderly couple wait for a bus. They are Bosnian Muslims--Bosniacs--and this is their first trip to Jajce since October 1992. Then, as Serb artillery shattered the once idyllic tourist town, they fled on foot, carrying what they could on their backs. The bus is late, and they are restless. The authorities in Jajce are none too friendly to returning Bosniacs. One weekend last summer, the town's police winked as a Croat mob evicted hundreds of Bosniacs who had returned. Only vigorous intervention by international diplomats and troops convinced the authorities to let the returnees back. An uneasy calm has now settled on the town.

I ask the couple whether they will ever live again in Jajce, and they shrug. Their old apartment is in the center of town, they explain, and the authorities are particularly unwilling to see Bosniacs in the town, which is now almost entirely populated by Croats. On this visit, they only looked at their old apartment from the street, not daring to enter the building. Maybe next time.

We round a bend on the mountain road, and the town of Drvar opens up below us. It's late April, and a colleague and I are in western Bosnia. As we begin the descent into the town, we run into a NATO checkpoint. Two days earlier, Drvar had witnessed fierce riots by Croats against returning Serb refugees. The United Nations office in the town was burned to the ground, and the leader of the Serb returnees was dragged through the streets. The Canadian troops suggest that we go through the town with a military escort.

Later that day, we meet seven refugees holed up in an apartment building. Threatened during the recent riots, they are now protected by some 80 NATO troops and a handful of tanks. As we speak, one woman glances about her at the broken glass and charred vehicles left behind by the violence. She shakes her head as she reminisces about the good life here before the war.

She lives on the outskirts of the town. When the riots began, some heavies visited and said that her time in Drvar was short. So she came into the town center seeking the protection of the international community. We speak for about 20 minutes, and then it is time to go. She files back into the apartment building, and the troops resume their post at the door. She is in her hometown, but she is not yet home.