Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

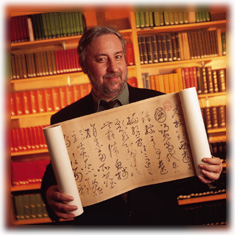

Conant University Professor |

The Chinese literary tradition is vast by comparison to our own. China's first anthology, The Classic of Poetry, was assembled during the Zhou dynasty (1020-221 b.c.), about two and a half millennia ago. Beyond this extraordinary history is the equally remarkable length of many works in Chinese. Several of the great plays, translated into English, are more than 1,200 pages long. The complete body of work is enormous, and the arduous task of translating this motherlode of cultural riches is the kind of endeavor one normally associates with eleventh-century monks working by candlelight. Yet Stephen Owen, a Harvard professor beloved of his students, recklessly backed himself into just such a project over an academic point. The result is the 1,200-page Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911--another hefty offering from Norton--which he edited and translated himself.

"There are these clichés about translating poetry," the Conant University Professor explains. "One is that when you're reading poetry you're never really reading just the words and how well the words are [expressing a thought], you're reading them against everything else you've ever read." So, when people started asking him about the translation of poetry, he told them that the only way to do it right is to translate "the whole tradition. Out of that insight," says Owen, "you realize, yes, you can translate texts well if you translate enough of them, so that you create families of texts to play off against one another."

Colleagues call Owen a soaring and highly imaginative free spirit, comparing him to the eighth-century monk and calligrapher Huai Su and to the foremost Tang dynasty poet, the unfettered, convention-defying Li Bai, Huai's poetic peer. But Owen clearly also has an extraordinary capacity for hard work. He completed the monumental task of translation for the anthology over four summers, introducing new texts each fall to his Harvard course in Chinese literature. Then he watched how students responded. "If it didn't work," he says, "I threw it out." Gradually, drawing from the established Chinese canon, he built up a family of texts that he describes as a mediation between what the Chinese see as Chinese literature and what works in English. Creating the whole anthology himself, he says, was "not so much ambitious as mad--not so much about me, but [about sharing] my understanding, informed by having read a lot of Chinese writing about their literature and what they value, and by dealing with students. It's a case of listening to others," says Owen. "In that sense, it's probably the most pragmatic anthology ever done."

TEXTCREDIT TEXTCREDIT |

Critics of Owen's plan to translate the entire anthology solo charged that the variety of voices would be lost when one man translated the work of many poets across millennia. Owen disagreed. "I thought of myself as writing a drama," he says, "a huge play. If you're writing a play, you don't make one person sound like another! You create a family of different characters who become interesting in relationship to one another." Owen has been teaching some of the poets for 25 years, so that, he says, "Every time I teach them in Chinese, I hear them in English in the back of my head. They have become characters I know."

There are advantages to doing all the work oneself. For example, says Owen, "if a poet writes something in the third century b.c., and someone in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and seventeenth century quotes it, I've got it verbatim. If someone plays on a phrase, it's verbatim. If you change a metrical style by certain conventions, you can tell the metrical style changed. There are all sorts of ways--if you are doing it yourself rather than with a group of people--that you can integrate the tradition and make differences coherent." Thus the phrase "sunlight circling dragon scales," from Du Fu's circa a.d. 767 Tang dynasty poem "Autumn Stirrings," reappears in precisely the same words when the eunuchs sing the emperor's praises in the "Declaration of Love" from Hong Sheng's Qing dynasty play The Palace of Lasting Life, written almost a thousand years later.

Thousand-year-old allusions, virtually impossible in English because of changes in the culture, are not uncommon in Chinese, with its continuous, nearly 3,000-year-old literary tradition. "Unlike the Chinese, we live in a culture of supercession," says Owen. "What we did in the '80s is no longer what we do in the '90s--when something new comes in, it replaces something old. But up until the twentieth century, the Chinese culture was one of accretion. New things were always happening--the Chinese just didn't forget anything old."

"The Chinese have a very different relationship with the past," says Owen. A case in point: When the anthology first appeared, Owen received "a wonderful letter from a gentleman who was a descendant of the Song lyricist Qin Guan," from whose poetry Owen had included just one example. "This man was very upset that I had not included more of his ancestor's poems," says Owen. What is remarkable about this family partisanship is that Qin Guan was writing in the eleventh century. Where the family line is concerned, "They're not kidding," Owen says, citing a recent Taiwanese case in which a man sued, successfully, for defamation of an eighth-century ancestor.

In the Chinese written tradition, new literary forms were added constantly to those still in use, creating a rich field of possibilities. Many of the allusions, stories, and poems that are part of the shared cultural repertoire come from the early period. Owen likes to tell his students how Mao Zedong kept a court poet who, when he wrote a "happy birthday" poem to the Communist chairman, rhymed the word "Moscow" using Tang dynasty, rather than modern, rhymes.

Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that a modern reader of classical Chinese can look at something written 2,000 years ago and not find the language strange. This is not the case in English, in which the language of Beowulf, or even Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, is quite unlike its modern descendant. "In Chinese, it doesn't matter whether this is 1,000 b.c. or a.d. 200," Owen says, "because the culture is all one big room, with far less alienation between the past and the present than we have. When [Chinese president] Jiang Zemin wants to talk about his hatred [of Japanese invaders], for example, he does so through allusion to the Nan Lushan rebellion, which happened in a.d. 755," says Owen. "It's a way of thinking about the present with these past texts."

Fewer Chinese texts have been lost than one might guess, largely because China discovered printing in the ninth century. By the eleventh century, the country had a flourishing commercial printing industry. Ask Owen about the significance of Gutenberg, and his face lights up: "The significance of Gutenberg is that it happened in the West," he says with a puckish grin. The Chinese even had movable type before Gutenberg, according to Owen, but generally carved whole pages of characters because that was more practical.

Despite the good-natured jab about Gutenberg, Owen's aim in the anthology is not to subvert Western notions of cultural primacy, but simply to make Chinese literature part of American culture. "There are lots of Chinese in the United States," Owen points out, "and their children will be culturally American. A good number of these children will marry non-Chinese. Their children's children will marry non-Chinese, probably, and so on. It's a good old American story." What is now an ethnically separate group, often culturally distinct from the mainstream of America, will no longer be so in a hundred years. After all, says Owen, looking to the past for analogies, a hundred years ago "an Irish student did not come to Harvard. Irish culture was not really considered part of European culture. Dante was read by intellectuals, but was generally considered too papist. American culture was essentially West European Protestant. Now an Irish immigrant's son sits in a Harvard lecture hall and is told that Shakespeare is his culture, Dante is his culture, that there's this one thing we call Western culture. And the Irish student belongs to that, and we take that so much for granted that we forget that it wasn't so long ago that the definition of what American culture was did have some rather radical exclusions. People look at me when I say this, but I think that in a hundred years the definition of American culture is going to be, again, much broader--not artificially multicultural in any sense, but just taken for granted that 'Yes, there's all this great stuff, and it's all part of our background.'"

If all those marriages that Owen is anticipating do take place, Chinese culture will be a part of every American's background. Everybody will have a Chinese great-grandmother or great-grandfather. And we'll all have Owen to thank for having seen our cultural baggage safely through customs.