Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

Please note that, where applicable, links have been provided to original texts which these letters address. Also, your thoughts may be sent via the online Letters to the Editor section.

EDITING SHAKESPEARE

Jonathan Shaw's piece "Anthologizing as a Radical Act" (July-August, page 38) ascribes to Shakespeare's editors up to our more enlightened present a tradition of "silently stitching together discrepant versions" of the plays. That is simply a myth. Editors of Shakespeare at least since the eighteenth century have routinely conflated all available readings of his text, most of them deriving from the quartos and First Folio of 1623, to produce a text as close to what he left us as possible. They haven't done this surreptitiously, and the text they settle on does not, as Shaw states, "hide the fact" that variants exist; any reputable edition lists them at the foot of the page or the end of the play. I do this in my editions of King Lear (Signet, 1963) and All's Well That Ends Well (New Cambridge, 1985).

Though editors are aware that different versions of Hamlet and Lear survive, most don't, unlike Professor Stephen Greenblatt, indent lines from one text within the body of the other, or reprint different texts on facing pages. They think this would shirk their responsibility as editors, which consists in rational choice on the basis of objective principles. Laying out these principles has been the chief business of the science of bibliography, an enterprise this article seems unaware of. Its conclusions, hardly slapdash or merely subjective, tend to give priority to the First Folio, as closest to what Shakespeare wrote. Even when a quarto's reading will seem to the personal taste of the editor esthetically more attractive, he will stick to the Folio, provided its reading is at least tenable. If he is learned, as any Old Historiographer should be, he will appeal to the entire range of meaning in defense of the word he chooses, or to a consensus established over time, or even to the peculiarities of his author's handwriting. It isn't true, as you inform us, that "No manuscript in Shakespeare's hand is known to survive." Scholars generally find his hand in the unprinted play, Sir Thomas More.

Unlike Greenblatt, they credit him with "an ultimate intent," supposing that he was an author, that is, a writer who had something he wanted to say. This particular writer was intensely social and political, as the plays attest, and a good editor will highlight the context from which they derive. Literary study has its fashions, however, like anything else. New critics, a generation ago, paid more attention to foreground than background. Marxists do the reverse. But credentialed critics in any period have understood that Shakespeare wasn't an airborne spore. No one will disagree when Greenblatt reiterates this, but there needs no ghost come from the grave to let us in on the secret.

The play Shakespeare said his say in wasn't the same as modern TV shows or basketball games, analogies Greenblatt proposes. It was a game all right, but played for mortal stakes. No intimation of that here. Harold Bloom, whom you dismiss, is closer to the mark in calling works of art like Shakespeare's transcendent. After all, we don't read him because he is of his time, but because he stands above it. There is a spurious democracy in asserting otherwise. Too bad that Harvard should endorse it.

Russell Fraser, Ph.D. '50

Warren professor of English literature and

language emeritus, University of Michigan

Ann Arbor

Professor Stephen Greenblatt replies: reputable editors of Shakespeare, Professor Fraser writes, print those texts "closest to what Shakespeare wrote." Aye, but there's the rub. For about half of the surviving plays, there are two, and in some cases three, different versions, each with some claim to authority. Editors have disagreed, often with an indignation and passion echoed in Fraser's letter, about the "objective principles" that should govern the choice of what to print. The Oxford edition, upon which the Norton Shakespeare was based, starts from the assumption that Shakespeare was a man of the theater, writing--and revising-- scripts for performance by a repertoire company. There is, in this view, no platonic form of each of the plays, no perfect version in the mind of the playwright; the plays are in process. The First Folio is certainly important, but the Norton and Oxford editors would dispute the claim that it automatically be given priority over all other substantive texts.

It is true that many earlier editions of Shakespeare do indicate somewhere in the editorial apparatus where discrepant versions have been conflated. But even if they have glanced at the table of textual variants, most readers of conflated Shakespeare plays will come away with the impression that they are reading the definitive version, the text that the author intended to leave for posterity. The Norton Shakespeare attempts to counter this impression, in the all-important cases of Hamlet and King Lear, by signaling the existence of legitimate alternatives, alternatives that call into question any notion of direct access to what Fraser longingly calls Shakespeare's "ultimate intent."

RADCLIFFE'S FUTURE

Perhaps the Radcliffe trustees should consider opening a distinguished college for women in Cambridge ("Radcliffe Quandary," July-August, page 61). They have the endowment and real estate to do so. There are many very capable faculty members (male and female) whom Harvard overlooks at tenure time. And, as for the links to large research universities that such a college might desire, what about MIT?

Ann Glendening '72

Spokane

Editor's note: "Radcliffe Quandary" includes a technical error regarding Radcliffe athletics, in that it describes Radcliffe crew and sailing as varsity sports that compete for Radcliffe, not Harvard. Since Radcliffe College is not a member of any athletic conference nor of the NCAA, Radcliffe cannot officially compete in sanctioned intercollegiate events. The women athletes who spoke at the rally in support of preserving Radcliffe College, and whose words were reported in the article, were describing their own personal, subjective feeling of competing for Radcliffe, rather than the institutional status quo. The terminological confusion here is a minor example of the larger issues of identity surrounding Radcliffe's status as a "college," the topic explored in the article.

SPECIAL DEALS IN FINANCIAL AID

In the tough, competitive world of college admissions, when scholarships are often part of a price-war to get the best students, financial-aid officers have a hard time--caught between market pressures to "buy the best" and a tradition which bids them award aid strictly according to financial need. It appears, however, that Harvard's admissions and financial-aid people are abandoning some of their own principles. It is not clear that they have to. In your past two issues ("Faster Track on Financial Aid," May-June, page 74, and "Surging Yield," July-August, page 64), you report moves by Harvard's top competitors to cut student loan burdens (Princeton, MIT) and reduce the role of assets in calculating financial need (Princeton, Yale, Stanford). These moves were systematic, open concessions to identifiable groups, especially to middle-income students stressed by high tuitions and sometimes courted by non-Ivy colleges offering fat merit scholarships not based on need--a practice that all the Ivies and some other very selective colleges still eschew.

Harvard's response has been less transparent. Statements reported in your own pages have been curiously circumspect. The financial-aid office, we are told, has been given more money and been talking to many more applicants. Financial-aid director James Miller has spoken of doing a "lot of heavy lifting" and "using as much creativity as we could, within our guidelines." The president and dean of the faculty have told him to "do what you have to."

Elsewhere the University has been somewhat more explicit. Alumni interviewers have learned that financial-aid offers will be "competitively supportive," and applicants have been told "not to assume we will not respond [to] particularly attractive offers" from other colleges. The New York Times (June 21) reported the case of a high-school valedictorian who got Harvard to increase her scholarship by "thousands" on the strength of a merit-scholarship offer from Rice.

Evidently Harvard has been doing special deals for students whom it really wants, who conceivably need some financial aid, and who can document big offers from elsewhere. (This is different from raising the scholarship offer on the grounds of new or corrected information about family circumstances--a practice that colleges admit to quite readily.) In other words, squeaky wheels have been getting extra grease. These wheels tend to be advantaged wheels, propelled by college-smart parents and educational consultants. One can guess that these consultants are telling their most promising clients to apply to colleges that offer big "merits" if they want to get more money out of Harvard.

Apart from being inconsistent, these special deals amount to preferential packaging--more scholarship, less loan for hot talent. For years this has been against Harvard policy; it has been considered unfair and invidious. Harvard instead has proclaimed its adherence to what used to be called equity packaging: all students with financial need, black or white, brilliant or merely bright, get the same amount of loan and job before qualifying for scholarship. (A variation is the official Princeton one of cutting loan burdens only for lower-income students.)

In today's market, few colleges believe they can afford such principles, but Harvard has been one of them. Can it, too, no longer afford to do this? As you reported, Harvard achieved this spring an astonishing selectivity rate, accepting just 12.3 percent of undergraduate applicants. If Harvard had lost rather more, desirable applicants, would this have been such a disaster for the University--or for American civilization? I doubt it.

When the University has completed its promised review of financial-aid policy, I hope it will produce a public and forthright report, addressing all the costs and benefits of what it proposes and actually does.

Rupert Wilkinson '61

Falmer, Brighton, England

ARMAGEDDON ECONOMICS

In James Glassman's "How Nations Prosper" ("The Browser," July-August, page 19), regarding the alleged triumph of Hayek's market model, there is no mention whatsoever of the effects of the market on the environment. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, the market economy is a poor way to manage an economy, but it is better than any alternative. Like democracy, the market needs checks and balances to keep it from running amok. Just as restraints on democracy are necessary to protect minorities and individual rights, restraints on the market are essential to protect the poor and the environment. The environment is especially vulnerable in developing countries or in former Communist countries that are trying to evolve into market economies. It is ironic that we have a series of films that depict destruction of the planet from some vagrant comet or asteroid. The real dangers are right here on earth where an unchecked market economy, or Keynesian attempts to fine-tune the economy, can plunge a country, or even the world, into an ecological disaster.

In all fairness, however, it is not just a matter of the market economy versus planned or socialist economies. Any public policy that is driven exclusively by short-run economic criteria regardless of environmental consequence can destroy the environment. The environmental record of Communist regimes is even worse than that of the capitalist world. Chernobyl is but one example. No economic theory today is worth the paper (or hard disk space) it is written on unless it fully takes ecological costs into account.

Elijah Ben-Zion Kaminsky '47, Ph.D. '62

Tempe, Ariz .

GRAPHIC TYPO

The graphic "To the Finish L:ine" on page 66 of the July-August issue shows that the Medical School has raised $225 million out of a goal of $102 million--and that this translates to 102 percent being achieved. Is this the new math?

Perplexed, I decided to add up some of the other numbers in the table. The total under the "goal" column comes up almost $300 million short of the $2.1 billion claimed in the caption. Perhaps the secrets behind these apparent anomalies lie somewhere in the depths of the accompanying prose, but, as a stand-alone, the graphic comes up short.

James Perkins '86

Brookline, Mass.

Editor's note: reader Perkins caught a glaring typographical error; the Medical School's goal was $220 million. The balance of the $2.1 billion related to Campaign goals apart from funds allocated to specific schools--notably, presidential funds for new programs, common facilities (the libraries, for example), and other priorities.

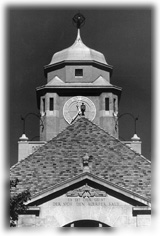

Adolphus Busch Hall. The inscription above the door, from Friedrich Schiller, reads "Es ist der Geist der sich den Körper baut" and may be translated as, "It is the spirit that creates the body." HARVARD UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Adolphus Busch Hall. The inscription above the door, from Friedrich Schiller, reads "Es ist der Geist der sich den Körper baut" and may be translated as, "It is the spirit that creates the body." HARVARD UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES |

THE TROUBLE WITH THE HUMANITIES

As a teacher of history for more than 30 years, I can personally attest to the truth of the article by James Engell and Anthony Dangerfield on the state of the humanities in American universities ("The Market-Model University," May-June, page 48). But this truth--that the humanities are not getting their fair and necessary share of the academic pie; that relatively low pay with high teaching loads for its professors discourages the best students from becoming teachers of the humanities; that market-driven credentialing lowers standards for students--is a materialistic truth that is not the whole truth, and certainly not the humanistic truth.

Amidst seven pages of print, in only three paragraphs--about one-quarter of a page--do the authors acknowledge the impoverishment of the humanities caused by the "internecine wranglings" of humanists. This condition and something more in the current culture of the humanities point to spiritual causes of the crisis that also require a profound exploration which one cannot do in a brief letter.

In my experience, students do not simply choose to study in the courses and fields of professors with the highest salaries, as claimed. Especially outside of the hard sciences and the allegedly hard social sciences, all too many students seek simply and dumbly to have themselves and their views affirmed by professors. We in the humanities cater to their narcissism and meanly recruit their enrollment in many wrong ways: the inflation of grades, which I suspect is most pronounced in the humanities, and the deflation of critical comments on their written and oral work are two symptoms of the spiritual crisis of the professors. Why should students ultimately respect those who do not really challenge them, those who professionally lie to them? Why enter graduate school to join the professors of the admirable who act so contemptibly?

No matter how unfairly little money goes to professors and departments of the humanities, none is utterly impoverished. Improvements in humanities curricula are not so dependent on grants of money as is, for example, new instrumentation in science laboratories. Humanists could do more and be more respected if they could first grasp and employ their own humanity. Academics in general, and humanists in particular, work in colleges where there is no collegiality. Collegiality is a more important desideratum in the humanities than in the natural sciences because humanists have no commonly received method of inquiry that more readily enables even egotistical enemies to cooperate in a common enterprise.

If one wants a comrade in any worthy endeavor, one is more likely to find that creature in the army than in the university. Without comradeship, there can be no collective improvements that attract and convince more students of the personal worth of the humanities. And without greater enrollments, the bean-counters in the halls of administration will not materially encourage the humanities.

Let us take seriously, therefore, the message over the entrance to Adolphus Busch Hall, now headquarters of the Gunzburg Center for European Studies: it is the spirit that creates the body. To save the humanities, let us begin, not with the dollar, necessary as it is, but with the spirit.

Paul Lucas

Associate professor of European history

Clark University

Worcester, Mass.

During the past 30 years much academic work in the humanities, far from representing mankind's highest thoughts and aspirations, has degenerated into a series of faddish, politically motivated "isms"--deconstructionism, relativism, socialism, multiculturalism, radical feminism, et al. The fruits of these preoccupations, and the painfully impenetrable writing on ever more abstruse topics, are lack of interest in the humanities or contempt for them--not the ingredients for successful student recruitment! While by no means solely at fault for their demise, humanists in academia are certainly justified in looking in the mirror and saying, "We have met the enemy and he is us."

Michael J. Speidel, MCRP '80

Belmont, Mass.

Engell's and Dangerfield's theme is that decisions in academe are governed by monetary considerations and that the humanities are being shortchanged. Three types of decisions are said to be consistent with this theme: research, faculty compensation, and faculty size. Analysis of these decisions doesn't support that conclusion, either at Harvard or at other schools.

The sciences do indeed obtain much more research money than the humanities. The reason, however, is not that the humanities get less than they deserve. Research in the sciences typically is conducted by large teams using expensive equipment, whereas research in the humanities typically is done by one professor, perhaps with one assistant, and the work generally is done in a library at low cost. Moreover, the growth of new knowledge has been much more rapid in the sciences than in the humanities, and support inevitably has responded to this shift.

Humanities professors are indeed paid less than their colleagues in other disciplines. The reason is that universities pay whatever is necessary to attract top professors; the going rates are generally higher in some other disciplines than in the humanities. (And compensation is not always an important factor in attracting people; Harvard's president earns about a third as much as the president of certain peer academic institutions and a fifth as much as the chief executive officer of businesses of comparable size and complexity.)

As for the size of the humanities, the humanities departments have grown less rapidly than other departments. The reason is that fewer students take courses in the humanities than was the case a few decades ago. University administration would be foolish to increase the size of the faculty when demand is decreasing.

The authors imply that their arguments apply to the humanities in colleges generally. I doubt this. As a trustee of Colby College, I can report that the humanities there are thriving. (Colby may be one of the "pockets of health" that the authors acknowledge, but these schools should be recognized in any even-handed treatment of the subject.)

If a humanities faculty member does propose a worthwhile project, the funds are made available. Many humanities faculty members do less research than those in the sciences, but this is because their primary love is teaching. I suspect that they spend more time with students, both individually and in organized activities, than is the case at Harvard.

Colby faculty salaries are less than professors perhaps could earn elsewhere, but they don't prevent the school from attracting the best. The English department typically receives 300 applications for a tenure-track opening; in one recent case there were 400. They come from graduates of top schools. The junior faculty is enthusiastic about the Colby atmosphere, and the best of them stay.

Teaching at Colby is done by tenure-track faculty. There is no doctoral program, so there is no body of doctoral candidates to do the teaching that Harvard tolerates.

The humanities faculty is indeed smaller. When I was a student, Colby offered both Greek and Latin courses. As the demand for certain subjects decreases, the faculty decreases, subject to the firm rule that tenured faculty members are welcome until they retire. In the English and history departments, the demand continues to be strong.

Rather than bemoaning the growth of the sciences, humanities professors would do well to recognize that both are vital and the relative emphasis on each has changed for good reasons.

R.N. Anthony, M.B.A. '40

Hanover, N.H.

HURTING HANDS

Thanks for Sewell Chan's excellent article on Harvard students' developing repetitive strain injuries from computer use (The Undergraduate, "Hurting Hands," May-June, page 86). It seems shameful that Harvard hasn't responded adequately to the problem: that students still work at desks ergonomically unsuited to computers and must wait four weeks for a physical-therapy appointment. Perhaps Chan's perceptive account will motivate the administration to take student health more seriously.

Maya Fischhoff '93

Ann Arbor, Mich.

SILENCE ON SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Tara Purohit's "Undergraduate" column on sexual harassment at Harvard ("Breaking the Silence," March-April, page 71) touches on several important issues. Perhaps more disturbing than the actual harassment are the total silence regarding such issues that seems to be fostered by the administration and the resulting infringement on the rights of the victim.

Just before winter break during my freshman year at Harvard, a male resident of our dorm assaulted a female resident who also lived in the entryway. Although the woman immediately filed a complaint with the police, the administration declined to pass judgment on the offender until after the case had gone to court. The explanation offered by the administration for the "non-decision" was that, if the administration punished the offender before he was judged in court, the administration would be censuring a man who was still presumed innocent.

While I am in favor of an individual's right to the presumption of innocence, the message this non-decision sends to the victim is ambiguous at best. Should the victim have to face encountering this man on campus (not to mention in our dorm or in the upperclass house to which they were both later assigned) because the administration did not consider her complaint sufficient basis for judgment of the offender? As it happened, the offender was "encouraged" to take the next semester off, during which time his case went to trial. Although we learned that his lawyer arranged for a plea bargain involving counseling and probation, the administration still refused to divulge what (if any) action the University took in this situation, again citing the offender's rights. I question whether, at any point during the sequence of events, the administration stopped to consider the victim's rights as well.

As Purohit states in her article, "in its efforts to protect reputations, the College stumbles into another trap of silence." By declining to pass judgment on the offender, the administration is tacitly denying the victim her right to feel safe in her own environment. Victims of sexual assault and harassment would certainly feel more comfortable dealing with their terrible situations if they had greater assurance that the Harvard community would be sympathetic to and supportive of their positions.

Beth Raina Trilling '92

New York City

FOR RICHER REUNIONS

After reading Claudia Cummins's reasons for not attending our tenth Harvard reunion ("Why I'm Not Coming Back," July-August, page 81), I wish to thank her for her honesty and encourage her and others with so-called unpolished (or non- "Ivy-colored") lives to come back for reunions in the future. Our reunions will be richer for your presence.

Perhaps it is natural that at the tenth reunion, after a period of time allowing training and apprenticeships to be completed, I should sense an emphasis on professional development in the conversations taking place around me. Perhaps because it was only our tenth, we felt impelled to present ourselves to each other in our newly minted professional roles. And perhaps it is endemic to cocktail parties that small talk overpowers real talk. In any case, during the course of what was indeed a fun weekend, I wished for more opportunity to hear what was most real in my classmates' lives, to come to know them again behind the labels of occupation, and to continue living the connection that Millicent Lawton described in her (our) Class Day speech: that it is hard to find silence at Harvard College because we are always talking to each other, and that when we leave, as she worded it, "I am a part of all that I have met."

So, Claudia, thank you for writing so honestly. You reminded me that I cherish my classmates not for their achievements, but for the openness with which we talked to each other, then and now.

Marie C. Henson '88

Cambridge