Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

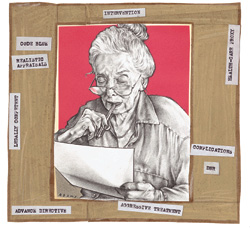

Illustration

by Lisa Adams Illustration

by Lisa Adams |

Tennis stops being fun when you can't concentrate. at the end of a tight doubles match, after I had watched my partner spray an easy set point into the net, I finally asked what was on his mind. "It's my mother," he said, as he packed up his rackets to hurry out the door. "She's in the hospital and she's not doing well. For 15 years, she's lived with my sister, who's devastated at the idea that Mom might die. But my mother says she doesn't want anything else done to her. I think she's depressed, but the doctors say that she has to make all the decisions. Now I have to drive up there and try to convince who's devastated at the idea that Mom might die. But my mother says she doesn't want anything else done to her. I think she's depressed, but the doctors say that she has to make all the decisions. Now I have to drive up there and try to convince my 88-year-old mother to let them put a feeding tube into her stomach."

Almost nothing can match the guilt and anxiety that surface when a parent is sick or dying. The sight of one's mother in an ICU bed may evoke the same rescue impulse as a child struggling in a swimming pool. But at some point, our parents lose either the ability or the stimulus to cooperate: while we search frantically for ways to maintain life, their bodies inexorably seek escape from it.

Fortunately, we do have tools to guide us through the process. Living wills contain people's instructions for their care in situations where they're unable to express their own desires. Although not recognized as a legal document in some states, the living will is usually followed by relatives and care providers. This advance directive allows you to specify the types of interventions that you would not want, such as the "electrical or mechanical resuscitation of my heart when it has stopped beating."

Almost all states have some legislation that permits you to designate a legal health-care proxy: a relative or friend who's responsible for making health decisions when you can't. Many people would rather have a root-canal operation than think about death, so once the health-care proxy and living will are filled out, you can almost hear a collective sigh of relief from the entire family. "It's done," they think. "We're prepared for the worst."

The problem, according to assistant professor of medicine Muriel Gillick, M.D. '78, is that the worst may be all you've prepared for. As Gillick, the author of Choosing Medical Care in Old Age: What Kind, How Much, and When to Stop, points out, there are myriad complex and potentially painful situations that can arise in elderly persons' lives before they lose the ability to communicate and make choices. Many elderly people retain responsibility for their own day-to-day medical care well into their seventies, eighties, even their nineties. And whether they are healthy, frail, or on the point of dying, they still must bear the outcome of their decisions.

America is a society obsessed with autonomy, with personal responsibility. Whenever possible, we try to put people in a situation where they decide their own fate. But, as my friend from the tennis courts discovered, people who have been judged medically and legally competent are not necessarily in the best position to make decisions. His mother was sick and apparently ready to die; this much he knew. But was she depressed? Did she really understand what would happen if she refused treatment? Was she really that unhappy with her life at home? Should he support her decision, or would he regret his acquiescence for the rest of his own life?

These are the times when a health-care proxy, a living will, or a "do not resuscitate" (DNR) order is of no help. The operating room is ready, the surgeon is trying to conceal impatience, the family is agitated and conflicted, and the patient just feels very, very tired. Meanwhile, the clock is ticking. This is no way to make a decision.

All of us need to think seriously and realistically about health needs and goals well before a health crisis puts us in a hospital or ICU bed. Physicians and family members can help by initiating discussions about health-care planning. Older patients in particular need a clear understanding of their health status: they may think themselves much healthier or sicker than they really are. An older person's regular visits to the doctor should include realistic discussions of the individual's medical status, and of what might be done to treat potential problems. Then patients can talk with their doctors about whether they want a particular treatment, or others that might follow should complications arise.

Launching such a discussion need not be painful, Gillick says. In her own practice at the Hebrew Rehabilitation Center for Aged (HRCA) in Boston's Roslindale neighborhood, she converses with many of the patients about medical planning.

"What it usually comes down to is a question of what's important," says Gillick. "I like to talk with people about the things they enjoy doing: walking, reading, painting, knitting, taking care of themselves--things that make life worthwhile. People usually have a very clear idea of what makes life enjoyable for them, and at what point they wouldn't want aggressive treatment."

When health crises arise, children are sure to be asked to counsel their parents about which direction to take. They should know just as much, if not more, than their parents' physicians about treatment preferences, and the way to find out is through regular conversation and communication.

"The best time for talking is when your parent is doing well," says Gillick. "I think that being down-to-earth and matter-of-fact is very helpful, instead of acting like you're talking about a terribly sensitive, terribly difficult topic. Reassure your parent that you haven't brought the subject up because she's sick, or because she's expected to be in trouble tomorrow. It's like an insurance policy; a plan for health crises is a good thing to have established, but it shouldn't be something that's arcane or frightening."

Frequent discussions about attitudes toward appropriate care not only help children counsel their parents, they make it easier for children to choose a course of action when a proxy is needed. Clear answers to these life-or-death questions are more important than ever because of a recent, widespread trend in DNR policy. A small but increasing number of nursing homes do not offer cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and a significant proportion of nursing homes--the Hebrew Rehabilitation Center for Aged among them--will not perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation on any patient who has not specifically requested it.

The reasons are simple, Gillick says. Resuscitation is a traumatic process, and elderly patients who undergo "code blue" procedures frequently don't do well. In a 1996 study of 811 in-hospital resuscitation attempts, almost half (44 percent) of the survivors studied had increased disability after CPR, and those over the age of 75 were five times more likely to have lost function than patients 55 and younger. Nursing-home staff members don't like the idea of subjecting patients to the full code without a very good reason.

Of course, there are always some patients who want medical attention and intervention, no matter what. In fact, two HRCA residents who have asked to be resuscitated are 98 years old. And that's fine, says Gillick: "It just shows that these people place a tremendous value on continuing to live, no matter what the consequences may be."

Life is a gift, and as people get older we feel that they've earned discretion as to whether and under what terms they will accept it. No matter how good their intentions, children who haven't kept current with their parents' attitude toward living can't be sure that they are helping, rather than hurting. Sometimes, a sick older parent really wants to fight; just as often, if not more so, they're ready to leave the battlefield with all the decorum they can muster. You'll never know which unless you ask.

FOR FURTHER READING...

Choice In Dying, 200 Varick St., New York City 10014-4810, (800) 989-will, a national not-for-profit organization, has a website devoted to end-of-life decision-making issues, "https://www.choices.org/".

The American Association of Retired Persons, 601 E St., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20049, (202) 434-2277, lists on its home page a section with information on advanced directives, "https://www.aarp.org/programs/advdir/adirhow.html".

A copy of the American Medical Association's booklet on advanced directives, produced in association with the AARP and the American Bar Association, is available at the End of Life Resources home page, "https://www.changesurfer.com/BD/Death.html".