Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

Then came the host of graceful-living Lydians who control all the mainland race. Princely commanders, Metrogathes and noble Arcteus, and Sardis rich in gold set these in motion mounted up with numerous chariots. In various squadrons...they are a dreadful sight to behold.

|

Architectural terra cotta depicting a Lydian, ca. 550 b.c.e. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

Architectural terra cotta depicting a Lydian, ca. 550 b.c.e. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

Such stories fed the curiosity of the late George M.A. Hanfmann, future professor of fine arts and curator of ancient art at Harvard's Fogg Art Museum, during his rigorous classical education in Germany between the world wars. (Born in Russia in 1911, he became an American citizen in 1940.) And in a sense, that unquenchable curiosity led, in the hot summer of 1958, to his first breaking ground for the Harvard-Cornell Archaeological Exploration of Sardis.

Hanfmann, who in 1971 was named the Hudson professor of archaeology, used to entertain his students and associates with the old Sardis stories around the dinner table at the excavation site. Never far from his side was his beloved wife and official recorder, Ilse, whom he called Meter Kastron, "mother of the camp."

Fourth to fifth century c.e. marble slab from the synagogue, incised with a menorah ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

Fourth to fifth century c.e. marble slab from the synagogue, incised with a menorah ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

His favorite storyteller was the fifth century b.c.e. historian Herodotus, still the principal source for Sardis buffs. Perhaps the practical and congenial Hanfmann appreciated the way Herodotus brought the Lydians down to earth. They were, after all, says Herodotus, "the first people we know of to use a gold and silver coinage and to introduce retail trade, and they also claim to have invented the games which are now commonly played both by themselves and by the Greeks."

They were excellent horsemen, too, a fact that paradoxically led to their stunning defeat in 547 b.c.e. by the army of Cyrus the Great. According to Herodotus, in a story Hanfmann loved,

Locally made cup in Protogeometric style, 1050-900 b.c.e.©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

Locally made cup in Protogeometric style, 1050-900 b.c.e.©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

After the rout, says Herodotus, Croesus, watching the Persian soldiers sack the town, asked Cyrus, "What is it that all those men of yours are so intent upon doing?"

Medallion from a mosaic floor, ca. 400 c.e. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

Medallion from a mosaic floor, ca. 400 c.e. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

"They are plundering your city and carrying off your treasures," came the reply.

"Not my city or my treasures," Croesus answered. "Nothing there any longer belongs to me. It is you they are robbing."

Hanfmann returned to these stories repeatedly. They were good stories, including even the occasional whopper. He mischievously framed his enthusiasm for Sardis within just such a one.

The Tmolus Mountains overlook the acropolis of Sardis. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

The Tmolus Mountains overlook the acropolis of Sardis. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

Others had explored Sardis. Christian pilgrims arrived seeking the city that Saint John, in the Book of Revelation, had scolded for "sleeping," shirking its high responsibility as one of Asia's seven first churches. Archaeologists and adventurers came digging, including the German consul Ludwig

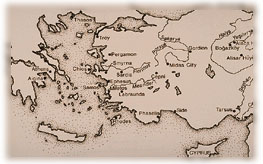

Sardis and neighboring sites in ancient Asia Minor and Greece. COURTESY UNIVERSITY MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

Sardis and neighboring sites in ancient Asia Minor and Greece. COURTESY UNIVERSITY MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA |

The Princeton campaign was halted by the First World War, Butler died in 1922, and a subsequent revival by a junior colleague the same year was ended by the Turkish-Greek war. Some surviving artifacts from the excavation were brought to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. (Today all excavated material must by law remain in Turkey.) Hanfmann, a junior fellow at Harvard in 1938, was asked by George Henry Chase, the first Hudson professor, who had been a member of Butler's team, to share with him the publication of the Sardis vases. Thus was sharpened the young scholar's appetite for all things Lydian.

Finally, in May of 1948, during the spring rains, George and Ilse Hanfmann visited Sardis. He recalled the experience, characteristically, with an anecdote.

"I was now determined," Hanfmann then states, "that a new excavation of Sardis was needed." To which end--"under the Harvardian system of ETOB ('each tub on its own bottom'), I had to find the means." It took him a decade, but the means eventually were found, including--in addition to gifts from several foundations--grants from the Corning Museum of Glass and the American Schools of Oriental Research, both of which for many years shared the sponsorship of the excavation. (A. Henry Detweiler, associate dean of architecture at Cornell, Hanfmann's first field adviser, was president of the American Schools of Oriental Research.) A private group called the Supporters of Sardis was also formed, numbering 47 the first year.