Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

Once upon a time, Boston and New York City and towns in between each determined their own, local time--typically with a sundial. Noon came about 35 minutes later to New York City than it did to Boston because time depends on longitude, and the sun moves along at 15 degrees an hour. "Each railroad in the mid nineteenth century ran according to the local time of its main station," says William J.H. Andrewes, the Wheatland curator of Harvard's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Scheduling confused even the managers of railroads, whose trains collided head on, which was a hell of a way to run a railroad. "If public transportation was to work," says Andrewes, "there had to be standard time and accurate timetables." In December 1857, the Harvard College Observatory started the world's first public time service, and by the 1870s was finding Cambridge time by the stars and distributing it, for a fee, to much of New England. In 1883, a federal law divided the United States into four time zones. Standard time made sundials quaint.

The Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments has 551 sundials, and the Houghton Library more than 1,000 books on dialing, collected most-ly by David P. Wheatland '22. Selections from this trove, with astrolabes and nocturnals, will be shown in The Art and Science of Finding Time, at the Houghton from December 18 through February 26. Among the books will be Gérard Desargues's La manière universelle de Mr. Desargues, Lyonnois (Paris, 1643), about the making of sundials. Its frontis-piece, at right, depicts a robust lady propping on her thigh a heavy, slate, vertical dial. Above her left shoulder is an equatorial dial.

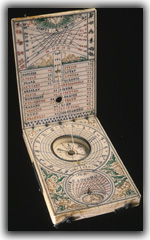

Also on view will be the portable, ivory, diptych dial at left. (Harvard has 80 diptych dials, the largest collection in the world, says Andrewes.) Measuring 4 1/4 inches long, it shows the latitudes of various cities so that travelers can set the dial appropriately. It tells three forms of time: regular hours (1-12, 1-12), Italian hours (1 through 24, beginning at sunset), and Babylonian hours (beginning at sunrise). It has a dial for converting lunar time to solar for operation by moonlight. Not visible in the picture is a wind vane to help predict weather. The dial is signed by Leonhart Miller, who made it in 1636, the year of Harvard's founding.