Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

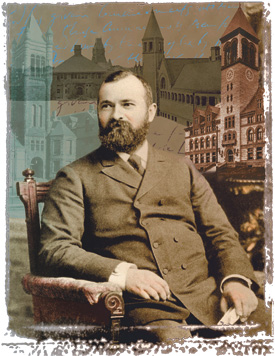

Rindge in later life, and (left to right) Harvard-Epworth Methodist Church, the Manual Training School and public library, and Cambridge City Hall. (The juxtaposition of school and library was intended to foster a close relationship between students and the books they might learn from.) Although the old school has been replaced by a new high school, the other three buildings are in full use. All were designed by architects influenced by H.H. Richardson. RINDGE PORTRAIT AND IMAGE OF CITY HALL FROM CAMBRIDGE OF EIGHTEEN HUNDRED NINETY-SIX (1896); Photomontage by Bartek Malysa. Photographs courtesy the Cambridge Historical Commission |

Frederick Hastings Rindge, Cambridge's most important individual benefactor, was a "townie" who entered Harvard in 1875. The son of Samuel Baker Rindge, a successful Cambridge merchant and businessman, Frederick was the only survivor among six siblings who grew up in the "Rindge mansion," which still stands at the corner of Dana and Harvard Streets. At Harvard, he was a loyal and enthusiastic student, joining the Art Club, the A.D. Club, the Glee Club, the Hasty Pudding, and the Institute of 1770, and becoming class secretary, a position he held until his death. But poor health forced him to leave the College in his senior year.

He traveled in the American West and Mexico, and eventually took up residence in California, where he had first visited at the age of 12, when he and his parents joined a group of enthusiasts on the first transcontinental train trip. In 1887 he married Rhoda May Knight and settled permanently near Santa Monica, fathering three children and establishing himself as a rancher (on 23,000 acres in Malibu), an investor in water and electrical utilities and oil, and a contributor to many Santa Monica institutions, including the YMCA and the local Methodist Church. He returned to New England only for short summer visits.

Nevertheless, from 3,000 miles away, Cambridge continued to exert a strong influence on the man who had been educated in its public schools and had become, on his father's death in 1883, the sole heir to a fortune estimated at three to five million dollars--much of it made in and around the city. With the encouragement of William E. Russell, A.B. 1877, a Harvard friend who became mayor of Cambridge in 1887, Rindge began to make a series of significant financial gifts to his hometown: between 1888 and 1890 he funded the construction of (and sometimes also bought the sites for) the city hall, the public library, and the Manual Training School, a vocational school for boys (now part of Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School). Besides his exclusively civic gifts, he made a major contribution to the building of Harvard-Epworth Methodist Church, adjacent to Harvard Law School.

Rindge possessed a deeply religious nature; his aim was to teach. "It is my intention to build didactic buildings," he wrote to his friend Russell, and he proceeded to do just that. He specified that his own name should not appear anywhere on the buildings, but he emblazoned the walls of the library with the Ten Commandments and composed the following inscription for the entrance to the city hall: "God has given Commandments unto Men. From these Commandments Men have framed Laws by which to be governed. It is honorable and praiseworthy to faithfully serve the people by helping to administer these Laws. If the Laws are not enforced, the People are not well governed."

Of all the institutions he helped create, none meant more to Rindge than the Manual Training School. For 10 years he was its primary source of support, overseeing its operations from California and corresponding frequently and at length with its first principal. Its stationery carried his name as "founder." He saw the school as a vehicle to influence future generations of Cantabrigians and as a doorway to the technological future for students who would not necessarily find their way to Harvard.

Unfortunately, he did not foresee his own sudden death, at the age of 48. A few sentences scrawled by hand left all his fortune to his wife. What happened thereafter is a tragic story. In her efforts to defend the ranch against the encroachments of the Southern Pacific Railroad, Rhoda Rindge spent millions, even hiring a small private army to patrol its borders. So excessive and protracted was her struggle that one of her sons sued her for dissipating the family estate. At her death, all the wealth her husband had accumulated had dwindled to a few hundred dollars.

Today Rindge is commemorated in Cambridge through the high school, Rindge Avenue, Rindgefield Road, and Rindge Towers, a public housing project. But one suspects that many in the "gown" community are unaware that an alumnus had such a material influence on the city of which the University is part. Rindge, whose life bridged "town" and "gown" as well as East and West, once explained his generosity in a letter to Mayor Russell:

It may be asked why so much has been given to one city....Cambridge was my father's and my mother's home and my own birthplace. The recollections of my boyhood center about it. On what is now the public library common I used to climb the hawthorn for its berries, which taste good to boys. Then, too, I believe that what is worth doing at all is worth doing well and thoroughly, and that concentration increases the power for good of gifts made or work done in the fear of God.