Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

[ Also see African Studies and Habitats for the Humanities. ]

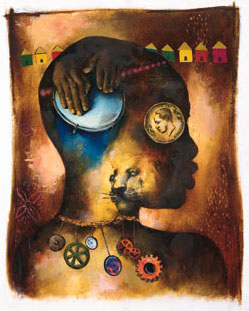

Illustration by Clemente Botelho |

"If you subject an egg and a stone to the same external environment," says kwesi Botchwey, "after a while, under the heat of the sun, a chicken will break out of the egg, but not out of the stone." The folkloric metaphor at first sounds odd, coming from an accomplished economic bureaucrat like Botchwey, who was finance minister of Ghana for 13 years before coming to Cambridge in 1995, where he now directs a new research program on development in Africa. But as he talks, it begins to seem exactly right: the perfect symbol for the changes he sees emerging as some nations of sub-Saharan Africa evolve in ways that may make them succeed in joining the world's economic and political communities.

It has always been a mistake, if perhaps a pardonable one, to imagine Africa as a homogeneous place. "When we're here, we speak about Africa and it has meaning," says Robert H. Bates, Eaton professor of the science of government and a faculty fellow in the Harvard Institute for International Development (HIID). "But when you're in Africa," where he has done extensive research and to which he travels twice a year to teach--"it makes no sense to speak about Africa. The internal variation is enormous. You can't write the story of Africa by going to Sudan during the drought or Zaire during the war." That is particularly so today, when alongside the long-running horrors of an Angola or Rwanda or Sudan one also finds political change coming to nations like The Gambia and Madagascar, and signs of economic growth in countries as diverse as Botswana and Mauritius.

The problems are still legion. New governments may have only a few years, or months, to prove that they can work. Economies based on exporting commodities--coffee, copper, gold, oil--can collapse when prices fall or when credit, already dearer than desert rain, vanishes as financial crises sweep through the more developed developing markets of Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America. As some African nations struggle to put behind them their unwanted role as proxies in the Cold War, and to move beyond the legacy of colonialism, they need traditional kinds of help--money and medicine--as well as education and good advice.

At the same time, they become fertile new ground for academicians eager to study everything from the equatorial home of the AIDS pathogen to art forms and ways of thought until now too little understood by developed nations' students of the humanities. With the emergence of new possibilities in Africa--the sorting out of Botchwey's eggs from the stones--has come an unheralded emergence of African studies and expertise at Harvard. Portraits of some of the practitioners and their work are presented here.

"The challenges posed by the developing nations animate both self-interest and conscience," wrote Bates in 1996. His conclusion--"It is Africa that constitutes the development challenge of our time"--now resonates even more loudly.

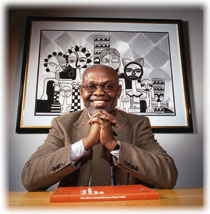

"Human action makes a difference" in shaping Africa's future, insists Kwesi Botchwey. Behind him, a woven silk hanging from Ghana represents carved wooden fertility figures from the Akra culture. Jim Harrison |

That belief certainly animates much of the new work on Africa under way at Harvard. In fact, the occasion for Nelson Mandela's historic visit to the University last September was the launching of Botchwey's "Emerging Africa" program, an ambitious effort to rethink--and improve--the course of economic development in the continent below the Sahara.

"East Asia and Africa were not that significantly different through the 1960s," Botchwey says, but they began to diverge in the early 1970s, and the gap widened into a chasm in the following decade. Now, the East Asian nation much of Africa most resembles is Bangladesh--not China nor Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, nor Taiwan, not even Indonesia and Malaysia, where (until recently) economic progress had become increasingly widespread. The data are stark: a 1997 report by HIID notes that "for the last two decades real per capita incomes have declined" in most sub-Saharan nations; from 1961 to 1995, food production per person rose 71 percent in Asia and 31 percent in Latin America--but fell in Africa; countries such as Congo, Mozambique, and Tanzania each had gross domestic product per capita of $135 or less in 1996.

"Obviously," Botchwey says, "geography, climate, and disease have an impact on development that is not always acknowledged. This," he is at pains to point out, "is not to suggest any kind of determinism--that since these countries are in the tropics, they are doomed." Rather, in explaining Africa's past and prospects, he insists that "it is important to see the complexity of the problems and the interrelatedness of all these factors" with culture and institutions. But in the end, he says, "Policies make a difference. Human action through mobilization makes a difference."

Much of that action, including many of those policies, has been misguided, Botchwey says. For all the development funds spent in Africa, "a lot of the aid went not to support good policies, but to support the geopolitical interests of the donors." In Zaire, to take a notorious example, "Everyone knew Mobutu wasn't using the resources wisely, but they saw him as a Cold War ally." There and elsewhere, Botchwey says, foreign aid "shored up despots, postponing the day of reckoning."

Now that day of reckoning has arrived. With their national economies looted or ruined by civil wars, many of the despots have been deposed. Bates has found extensive, if not always firmly rooted, political reform since the mid 1970s--what he calls "a deepening of institutionalized political competition." As a result, and facing the end of the aid that flowed during the Cold War, Botchwey figures, two-thirds of the 48 sub-Saharan countries have begun to adopt policies more conducive to economic growth. The "macroeconomic stabilization" measures he applied in Ghana--letting the market determine the currency's foreign-exchange rate, attacking inflation, collecting tax revenues, and balancing the budget--have become more commonplace.

But necessary as those steps were, they weren't and aren't sufficient to encourage sustained growth. "We had taxied to the end of the runway," Botchwey says of Ghana's experience, "but we weren't taking off." And so, "emotionally and intellectually drained"--and, ironically, finding that the country's liberalized governance made economic policymaking more subject to politicking--Botchwey decided to head for the academy, to reflect on his experiences and examine their larger implications.

"In the old story, the peasant goes to the priest for advice on

saving his dying chickens," wrote Jeffrey Sachs '76, Ph.D. '80,

Jf '81, Stone professor of international trade, in a 1996 article for the Economist. "The priest recommends prayer, but the chickens continue to die. The priest then recommends music for the chicken coop, but the deaths continue unabated." And so on, until, finally, "all the chickens die. 'What a shame,' the priest tells the peasant. 'I had so many more good ideas.'"

After decades of feckless aid, the African development challenge demands new thinking about "the interlinkages of economic growth with health, education, geography, environment, demography, macroeconomic policy, and institutions," as the Emerging Africa prospectus puts it. Many underpinnings for that new thinking have come out of HIID, where Sachs has been paying much attention to Africa since becoming director in 1995. HIID conducts practical research and provides economic and policy advice to nonindustrial nations and those making the transition to market economies. Emerging Africa, engaged in broader research questions, is housed in a new Center for International Development, itself an HIID-Kennedy School of Government venture focused on pioneering new approaches to beginning, and sustaining, economic growth. Botchwey's enterprise, therefore, is poised somewhere between the hands-on approach of HIID's field staff and the Kennedy School's scholar-policymakers, and, like them, promotes international collaboration and extensive exchange with academicians and government officials from other nations.

Sachs embodies this modus operandi. Now the man who would save Africa, he has previously been the man who would save Bolivia, Poland, and Russia. He went to these nations at their governments' behest, a wunderkind economist whose turn-on-a-dime policies earned him the nickname "Dr. Shock" (see "The Revolutionary Jeffrey Sachs," November-December 1992, page 48). In Bolivia, he slashed hyperinflation. In Poland, he converted a socialist economy into a market economy. In Russia, he tried to do both, and people still argue about whether the failure was his.

His prescriptions for Africa contain elements of all these prior experiences, beginning with an economist's interpretation of recent political history and new opportunity. "The rise of President Mandela and the end of apartheid were watersheds in African history," Sachs says. "An economic powerhouse [South Africa] began to play a broader role in overall African economic growth. A number of countries turned the corner on economic development. Africa's shortcomings and potentialities became evident simultaneously." In the Cold War's aftermath, he continues, it became possible to see Africa not as a strategic chessboard, but as "a place in need of attention in its own right. It's not as if Africa rose to the top of the radar screen for American foreign policy, it just rose from the bottom."

Part of that rise is attributable to an HIID paper, "A New Partnership for Growth in Africa," which subsequently transmogrified into the African trade bill passed by the House of Representatives just before President Clinton's historic visit to the continent last March. Although it ultimately failed to become law, the bill began to set forth a market-oriented new vision for development assistance: it would have eliminated duties and quotas on exports to the United States for the next 10 years and encouraged the establishment of free-trade zones. Those benefits were tied to one of Sachs's core beliefs--that it is worth extending "timely support for new democracies." To qualify for the benefits of the bill, countries would have had to prove a commitment to democracy, human rights, and a market economy, limiting eligibility to a handful of nations, including Botswana, Ethiopia, the Ivory Coast, South Africa, and Uganda.

Movement toward democracy is "widespread," says Robert H. Bates, shown with Yoruba, Ntum, and Kuba pieces from the Africa collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Jim Harrison |

Sachs has expressed other core beliefs that repudiate the prevailing wisdom about how to help Africa develop. His proclamation in the Economist went after the pillars of the development community: "The IMF [International Monetary Fund] is so obsessed with price stability it doesn't think very hard about anything else. The World Bank, on the other hand, has hundreds of good ideas but no priorities": calling for feeble and indebted governments to "introduce value-added taxes, new customs administration, civil-service reform, decentralized public administration and many other wonderful things--often within months." It is a critique Kwesi Botchwey can visualize with painful vividness.

To judge how far the continent must travel, one need only consult The Africa Competitiveness Report 1998, published by HIID and the World Economic Forum last spring, the first assessment of its kind. From 1991 to 1995, Botchwey notes in one essay, Africa attracted less than 2 percent of foreign direct investment funds worldwide--and three quarters of that was concentrated in the African oil-exporting nations. With 10 percent of the world's population, sub-Saharan Africa accounts for only 2 percent of world economic output, and a third of that meager share is South Africa's.

As the only remedy, Sachs advocates sustained, rapid growth--say 5 percent per year--like the revolution that transformed so many Asian economies. In theory, the key to such growth lies in reintegration into the world economy, based on political willingness to overcome prejudices against open trade and foreign investment instilled by not-so-distant memories of colonialism. So Botchwey's mission becomes a search for the best ways to put the HIID's new general theories into practice in Africa. Given his mantra that the development issues must be seen in their "multisidedness," that promises to be a daunting challenge, comprising infrastructure, institutions, and industrialization.

He notes, for example, that "everyone bemoans the small flow of international capital into Africa." But, given that the continent's "infrastructure is so underdeveloped," investors' inability, or reluctance, to put funds to work there is understandable. Whatever the causes--Botchwey cites government policies hostile to some kinds of investment, cumbersome statist procedures, and corruption--he is most concerned about the effect: "The fact that telephone density is so low, and that so many countries are landlocked and the road network and rails and ports and airlines are so relatively undeveloped, means that productivity is affected." Richard H. Goldman, an HIID agricultural policy adviser who has worked in Kenya and Malawi, gives a dramatic illustration: "In Kenya, even over the cheaper routes, it cost more to move maize from Mombasa to Nairobi, only 250 miles, than it did to move it from Louisiana to Mombasa."

Clearly, problems like these cannot be resolved solely through economic administration, by controlling inflation or correcting skewed exchange rates. Focusing on those priorities, Botchwey concedes, has done "some good," but most such efforts have fallen short because "for a long time, there has been no recognition that, along with sound policies, you need governments that could deliver them."

In much of sub-Saharan Africa, public functions taken for granted in the industrial world--educating workers, securing property rights, ensuring the privacy of domestic banking "so people could put their money there without a politician who doesn't like you coming and seizing it"--are not even a prospect. The vulnerability of private assets is especially costly for capital-starved African countries. It is in this context that Sachs's criticism of the World Bank's lack of priorities takes on its bitter meaning. In Botchwey's gentler formulation, this is just another symptom of development schemes too fragmented and superficial to sustain growth.

Instead, Botchwey prescribes comprehensive "strategic, long-term change," predicated on a fundamental shift "away from primary commodity exports to exports of manufactured goods and services"--nothing less than industrialization. Intellectually, this means deferring the classic short-term stabilization measures (raising taxes and tariffs) used to balance national budgets: "That's the worst thing you can do for a country," he says. Practically, it means creating the conditions that attract foreign capital investments to support long-term growth, mimicking East Asia's transformation. "So far, after 15 years of reform," Botchwey says, "hardly any country in Africa has made that shift to higher growth from real exports of manufactured goods."

What, then, must be done? First, he says, "the change has to start within the countries themselves," through better governance--the transformation from stones to eggs. "Without that," Botchwey says, "no amount of external aid can help." Then, international institutions like the World Bank must direct their support to those countries that have changed--not to all needy African nations indiscriminately--and within these countries, must support "critical things"--not glamorous projects like massive dams, but the subtler factors essential for economic progress: education and training, eradication of disease, and regional infrastructure schemes (telephony, coastal access roads) that are too taxing for local private investors.

Once the foundations are in place, Emerging Africa hopes to show how certain industries can thrive in specific locales. As Asian nations move up from labor-intensive exports, such as textiles, to higher-technology manufacturing, Botchwey sees the opportunity for African nations to succeed them, establishing free-trade zones to exploit their own comparative advantages, based, for example, on the availability of local cotton crops and inexpensive labor. Over the next two years, he plans rigorous studies on how exactly the obstacles to growth could be overcome in a few nations, enabling a few industries to take hold and succeed.

Despite the discouraging history to date, Botchwey is not on a fool's errand. The competitiveness report cites Mauritius, for example, which has overcome its one-time dependence on sugar sales to sustain 6 percent annual economic growth over three decades, elevating per capita gross national product to about $4,000. Isolated from the mainland (and from major markets), the country has evolved what the report calls "one of the most firmly rooted liberal democracies in Africa"--the necessary institutional context--and has successfully pursued a strategy of encourag- ing tourism and of processing textiles for export through a modern commercial harbor. If anything, the most pressing constraint on growth is the shortage of labor: unemployment now hovers around 2 percent.

"We are used to thinking of Africa as a region of gloom and doom, where nothing works," Botchwey says. But he believes that Africa can work in economic terms, once its people and governments determine to succeed, and once those who wish to help have acknowledged the complexity of the challenge. He calls what he sees "a turnaround," where for the first time it makes sense to ask seriously, "What would it take to make Africa an emerging region in the same way as Asia?"

A Nigerian attends an OPEC conference in Indonesia. Admiring his host's palatial estate, the visitor asks, "How can you afford this spread on your government salary?"

The Indonesian gestures toward a highway in the distance. "Do you see that road?" he says.

The Nigerian nods.

The Indonesian says, "Exactly."

A few years later, the Indonesian attends a conference in Nigeria, arranged by his former guest. Indicating his host's new mansion and lavish gardens with a sweep of his arm, the Indonesian says, "So, I see you took my advice. My only question is, where's the road?"

The Nigerian says, "Exactly."

Smita Singh, who is studying the politics of economic policymaking in Jakarta and Lagos as part of her doctoral research, tells the joke to illustrate a truism: in corrupt Asian countries, personal enrichment accompanied public investment, while in Africa, the looted funds all ended up in private pockets or offshore bank accounts.

The consequences for the affected citizens have been devastating. Nigeria, an oil-rich nation like Indonesia, was widely expected 30 years ago to power Africa's economies. Instead, according to the Africa Competitiveness Report, Nigeria's 1996 economic output per capita was $240--11 percent below the sub-Saharan average. Its economic landscape is a virtual metaphor for unfinished business. Singh describes Lagos as "post-apocalyptic," littered with abandoned construction projects, skeletal skyscrapers, highways that simply end. Power goes out in large sections of the city every night. Phones are often down. A company hoping to erect a new factory might also have to build and maintain its own power source and roads. "All people can do is sell things on the road," she says. "It's a country that is deindustrializing."

In other words, just what one would expect after years of brutal military government and the dashed hopes following the annulment of the 1993 election and the 1994 imprisonment of the winner, Chief Moshood Abiola (whose daughter, Hafsat '96, was then an undergraduate). Naturally, this political atmosphere affects government and business decisionmakers alike, says Singh: "When your time horizon is very short, you're not going to make long-term investments. You can see why people would rather put their money in Swiss bank accounts."

Overcoming that predilection, ingrained by decades of chaos, would obviously go far toward securing for much of Africa a more promising future. So what are the prospects for more humane governance in a continent where a traditional leader like Haile Selassie has more often been succeeded by a murderous Mengistu Haile Mariam and a junta than by an elected president and a parliament?

Much as the studies published by Jeffrey Sachs and others at HIID underlie the Emerging Africa initiative, new analyses by Singh, Robert Bates, and other students of government support Sachs's championing of Africa's "new democracies." What they are finding extends well beyond Nelson Mandela's transformed South Africa.

In an initial paper on "democratic transition in Africa," published in 1995, Bates found from a review of 46 countries that their political systems "more frequently exhibited attributes of democracy" in 1991 than in 1975--that evidence of political transition was "widespread." He also noted, however, that many of the changes were superficial "window dressing," applied like rouge by dictators eager to present a prettier public face to the world.

Subsequent papers by Bates and graduate students Singh, Karen Ferree, and others who have worked in Africa provide much deeper understanding of the real political changes under way there. Comparing the data over time reveals, for example, that for 46 sub-Saharan countries, the number of chief executives at least nominally elected rose from 18 in 1975 to 28 in 1991. Over that period, Botswana, Madagascar, and Mauritius enjoyed fully competitive legislative elections, and Benin and Zimbabwe moved dramatically in that direction. On the other hand, Mauritania, which had contested multiparty elections in 1975, had abolished them by 1991.

In the aggregate, Bates and his colleagues find "a deepening of institutionalized political competition in Africa during the period in question," but not uniform change, because a substantial fraction of the least competitive political systems remained that way--most often, mired in armed insurrections. The result: "an increasing level of heterogeneity in the political systems of Africa," and comparable divergence in nations' economic growth. In the precise language of statistical analysis, the Bates group is now quantifying the relationship between political change and economic performance. As Kwesi Botchwey might put it, the differences attributable to human choices are beginning to appear, and with them distinctions between stones and eggs.

Although these papers emerge from the comfortable confines of Cambridge, the data and observations underpinning them derive from fieldwork often conducted under challenging, even severe, conditions. Bates caught the Africa bug while he was still a student at the Pomfret School, in Connecticut. A progressive headmaster put together a program, funded by a wealthy parent, that sent Bates, several classmates, and students from other secondary schools to Kenya and South Africa, where he recalls seeing for the first time a weapon being loaded with the intention, if necessary, of killing people. He remembers being moved by "the incredible humanity of the people in the face of conditions that would challenge any of us to remain decent. When I came back, like so many others who have experienced Africa, I knew what I wanted to do with my life. It was that simple."

Bates went to graduate school, he says, because he discovered that professors could be paid to go to Africa. He has conducted research with his wife, Margaret (now dean of student life at MIT), in the mining townships of Zambia, and returned to study the life in a village on the Zambia-Zaire (now Congo) border. He remembers his hut there--"It was made out of clay bricks, with a wooden door frame and a thatch roof"--as fondly as village life: "Biologically, that's the way we're supposed to live. It's a very rich life."

From those earlier experiences comes a profusion of new scholarship today. With colleagues at Oxford, the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, and the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, Bates is launching in March a project entitled "The Economic Development of Modern Africa, 1945-2000." Under their direction, 30 researchers throughout Africa will prepare volumes for publication by Cambridge University Press--volumes that may have special credibility because of their indigenous origins. Meanwhile, Bates and a team of undergraduate and graduate students continue to collect data for the research that forms the subject of his course on "The Politics and Economics of Policy Reform." With a separate group of graduate students, he is beginning to study political conflict in Africa--particularly the worrisome recent rise of cross-border conflicts, as opposed to the civil wars that ripped through the continent but were contained within national borders by the superpowers during the Cold War.

Each of those inquiries depends on, and expands, a network of colleague-scholars here and in Africa. And so, enthusiastically, Bates sends his students out to do fieldwork, just as he and Kay Shelemay did (see "Habitats for the Humanities"). At around the time that Singh was avoiding being "shaken down" by police and armed robbers in Lagos (an experience she maintains was less physically challenging than earlier anthropological research in India, where she slept on a floor with 10 other people, enduring pecks from a chicken that also used the premises), Melissa Thomas, Ph.D. '98, was studying the rule of law in Mali. Thomas, who was in the graduate political economy and government program at Harvard and now works at the World Bank, found it prudent to stockpile food and water in case revolution broke out anew. And Karen Ferree, a graduate student in government and economics, learned that one of the risks of observing South Africa's party system was the likelihood of a violent bank robbery in her Johannesburg neighborhood every week or two.

For all that, Bates insists on the value of wearing out shoe leather. "It's just too easy to sit back here and grind numbers and make announcements," he says. "You think you're on to something, but if it doesn't resonate with your experience, it has a high probability of being wrong or silly. And the worst thing is, you'll never know that. The one thing I'm proudest of is my students in the field."

The other thing he and many Africanists are excited about--yes, even proud about--is the belief that they are in a position to help new ways of life emerge. "For a very long time after independence," Jeffrey Sachs says, "most countries had one-party rule. In the 1990s, there has been a shift to democracy, which is always difficult in low-income countries. The situation is highly desirable on the one hand, but reversible and subject to violence. Democratization and economic reform go hand in hand. There is not a case for sequencing them. You can't take for granted that democracy will function or survive. You need to help at fragile moments."