Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

|

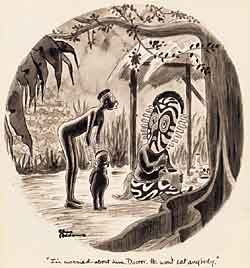

"When they're right, they're right to the point," says Melvin R. Seiden '52, LL.B. '55, who collects original cartoon drawings by New Yorker artists. "New Yorker cartoons are powerful and revealing testimony about America since the 1920s, and at their best they catch the essence of the spirit of the times--what's on people's minds--perhaps better than texts." Consider New Yorker cartoons on gender relations, for instance. "From the 1920s through the early 1960s, one of the more durable genres of New Yorker cartoons was what became known in the Art Department as Sugar Daddies," writes Hendrik Hertzberg in "Sex to Sexty" (New Yorker, December 7 and 14, 1998). "The joke is boy meets girl with a twist; that is to say, old, rich, powerful, and less than hunky but very randy (and almost certainly married) old man meets gorgeous, pneumatic, sexually attractive (and implicitly available) young woman....Each has something the other wants, and negotiations are in progress....Sugar Daddy to Bimbo, in a 1961 cartoon by Joe Mirachi: 'Look at it this way--you're a woman and I'm a millionaire.'" "Popularized by Peter Arno," writes Mary F. Corey in The World through a Monocle: The New Yorker at Midcentury (Harvard University Press, 1999), "these cartoons derived their humor from the idea of sex as a capital asset....The idea that women, whether they were trying to turn a man into a husband or a sugar-daddy, were essentially mercenary, not only persisted but flourished in the postwar years." "By today's standards, of course, cartoons like these are as politically incorrect as a whalemeat sandwich," writes Hertzberg. "But, also by today's standards, they add up to a critique of the dynamic that they seem to take as a given. They might even be seen as a pre-feminist indictment of the commodification of sex." Corey goes on to note a striking level of animosity reached in the New Yorker in its coverage of the battle of the sexes. "Particularly its cartoons, which were the magazine's most unconscious element, reveal an intense preoccupation with gender differences. The cartoons' perpetual subtext was that even when men and women were the products of the same social class, they inhabited antagonistic cultures." "The spread of the ideal of gender equality during the 1970s radically changed the social world that the cartoonists chronicled," writes Hertzberg. "More deeply than any other cartoonist, Lee Lorenz...has explored the evolving world of sexual politics....In 1993...he marks Christmas with a worried-looking Santa at his desk listening to a message over his intercom: 'A sugarplum fairy to see you, sir--with her lawyer.'" And see the devil getting her due on page 42. "As our consciousness has been ratcheted up," writes Lorenz ("Cartooning for Dummies," New Yorker, same issue), "some old favorites have been pensioned off: the cannibal parboiling the missionary; the wife driving through the garage door; the lecherous tycoon pursuing the not altogether unwilling blonde. But, as quickly as openings develop, new candidates step forward." At the least, our stereotypes are different from those of 1943 when Charles Addams drew his African cannibal--although her anxiety about her child, the finicky eater, which gave the cartoon its appeal, is timeless and universal. In 1975 Melvin Seiden started to collect drawings about business by New Yorker artists. He moved on to cartoons about art, then books, then everything, by almost every artist. He is depositing his collection, consisting now of some 500 drawings, as he builds it, in the Department of Printing and Graphic Arts at Houghton Library. He is also gathering drawings by Al Hirschfeld (see "Hirschfeld Center Stage," May-June 1998, page 91). An exhibition, prepared by Eleni Canellos and Anne Anninger, Hofer curator of printing and graphic arts, of 35 drawings by New Yorker artists and a number of photographs by Anne Hall of their sometimes-look-alike creators, will hang in Pusey Library from November 16, 1999, to January 14, 2000. |

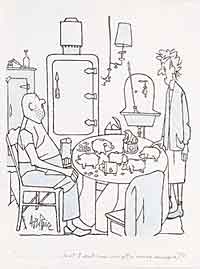

"Isn't it about time you get a money manager?" published in 1988. Above, George Price in Tenafly, New Jersey, 1987 |

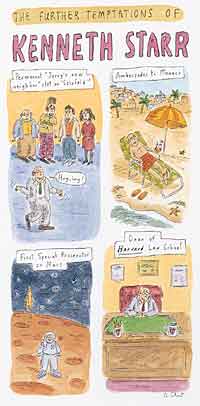

"The further temptations of Kenneth Starr." 1997. Roz Chast in Brooklyn, New York, 1989 |

"Honesty is the best policy. O.K.! Now, what's the second-best policy?" 1978. Dana Fradon in Newtown, Connecticut, 1988 |

"Apparently, that's his new little laptop." 1989. William Hamilton in New York City, 1987 |

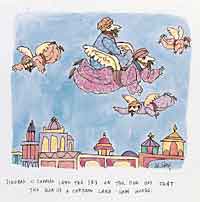

"Sindbad is carried into the sky." 1989. William Steig in Kent, Connecticut, 1987 |

"I'm worried about him, Doctor. He won't eat anybody." 1943. Charles Addams in New York City, 1985 |

"On the other hand, it's nice to see women in positions that go beyond mere tokenism." 1995. Lee Lorenz in Easton, Connecticut, 1992 |