Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

| The Manly Ideal | Films: Down Off the Farm |

| Music: Jazz with Ivy League Manners | Chapter & Verse |

| Off the Shelf | Open Book: Friends of France |

| The Manly Ideal | Films: Down Off the Farm |

| Music: Jazz with Ivy League Manners | Chapter & Verse |

| Off the Shelf | Open Book: Friends of France |

|

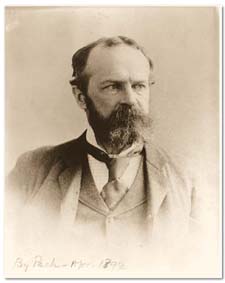

| William James Photograph courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard Unviersity (pfMS AM 1092) |