Main Menu ·

Search · Current

Issue ·Contact ·Archives

·Centennial ·Letters

to the Editor ·FAQs

|

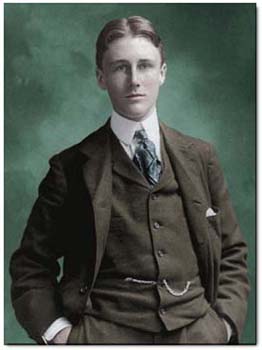

| Young Roosevelt, bound for Harvard, in the spring of his senior year at Groton, "a fellow of exceptional ability and high character." Photograph courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, tinted by Jim Gipe

|

|

Even adversaries admired his way with words, and the "wise sauciness"-in

Felix Frankfurter's phrase-with which he disarmed his critics. His speech

at the 1936 Harvard Tercentenary was a famous example. "This meeting

is being held," he began,

In pursuance of an adjournment expressly taken one hundred years

ago on the motion of Josiah Quincy. At that time many of the alumni of Harvard

were sorely troubled concerning the state of the nation. Andrew Jackson

was President. On the 250th anniversary of the founding of Harvard College,

many alumni again were sorely troubled. Grover Cleveland was President.

Now, on the three hundredth anniversary, I am President.

He cherished his Harvard connections. In the spring of 1934, when pending

legislation seemed likely to keep him from attending his thirtieth reunion,

he put on a White House reception for most of the class of 1904. Before

attending the Fly Club's annual dinner the following winter, he wrote Jimmy

O'Brien, still the janitor of the residence hall where he'd lived as an

undergraduate, inviting him to stop by the clubhouse and say hello. In the

presidential yacht, Sequoia, he visited Harvard's rowing camp at

Ledyard, Connecticut, where his freshman son, Franklin Jr., was in training.

The next spring he entertained two dozen Harvard oarsmen at a White House

dinner.

His enthusiasm was infectious. As a senior at Groton, his son James wanted

to go his own way and attend some other college. His father provisionally

agreed, James later recalled, but then began talking "hypnotically"

about the Crimson, the Fly Club, the Pudding, and his Harvard friendships.

James became the fifteenth Roosevelt to enroll at Harvard; many more

were to come.

Love it he might, but Harvard did not always love him back. President emeritus

Abbott Lawrence Lowell was rude to him when the Tercentenary exercises were

being planned. When he first ran for president, a straw vote held by

the Harvard Crimson showed a three-to-one preference for Herbert Hoover.

Four years later a Crimson editorial called the president-a former Crimed

himself-"a traitor to his fine education." In irate letters

to newspapers and the Harvard Alumni Bulletin, many older Harvard

men took the same line.

Yet he was not without honor at Harvard. At the age of 35 he was elected

to the Board of Overseers. In 1929, when he was governor of New York, he

was elected chief marshal at Commencement. He gave the Phi Beta Kappa Oration,

received an honorary degree, and spoke at the afternoon meeting of the alumni.

And in 1936, as the nation's chief executive, he spoke at the Tercentenary

exercises.

Two days after his death in oce on April 12, 1945, mourners jammed the Memorial

Church for a service led by Willard Sperry, dean of the Divinity School.

"We have lost one of our own members," said Sperry. "It would

be presumptuous to say that elsewhere there is no sorrow like our sorrow.

But our sorrow is touched with a humble and proper pride that this society

was one of the shaping forces which fitted him for his duty and his

destiny.

"He will live in the memory of generations to come," said the

dean, "as one with whom his own time had dealt, if not unfairly, at

least austerely. He is a casualty of these costly years of war."

A fortnight later the Alumni Bulletin published tributes from five

distinguished alumni. Older readers contributed reminiscences of his undergraduate

days. But the surprising fact is that no lasting memorial to Franklin Delano

Roosevelt was ever established at Harvard.

A fortnight later the Alumni Bulletin published tributes from five

distinguished alumni. Older readers contributed reminiscences of his undergraduate

days. But the surprising fact is that no lasting memorial to Franklin Delano

Roosevelt was ever established at Harvard.

The institution dealt less austerely with the Harvard-educated presidents

who preceded and followed him. The name of Theodore Roosevelt, class of

1880, LL.D. '02, is cut in stone on the 1880 Gate, outside Lamont Library,

and carried on by the library's Theodore Roosevelt Collection. When John

F. Kennedy '40 was assassinated, Harvard's school of public administration

was renamed in his honor. But no Franklin D. Roosevelt Center, no Roosevelt

chair of political science, no Roosevelt lectureships, scholarships, or

fellowships memorialize the most famous American of his time, a man who

overcame severe physical disability and led his nation and its allies through

the most desperate days of the twentieth century. Only a modest plaque marks

his old rooms in Westmorly Court.

With its manorial façade, diamond-leaded windows, and oak wainscoting,

Westmorly was the most ornate of the privately owned residence halls that

lined Harvard's "Gold Coast." On Bow Street, opposite Saint Paul's

Church, the building was new in the fall of 1900, when Franklin Roosevelt

and Lathrop Brown moved in as freshmen. In the fashion of the day, they

decorated the walls of their first-floor suite--now Adams House

B-17, a faculty office--with school pennants and banners, team pictures, beer

steins, and social invitations. The roommates would stay there four years.

Frank Roosevelt and "Jake" Brown, both New Yorkers, had become

close friends as students at Groton School. Frank's Groton career had been

unexceptional, but his teachers liked him. He loved to sail and had thought

of going to the Naval Academy, but he applied to Harvard at the behest of

his father, who had studied law there. Frank's best college recommendation

came from the Reverend Sherrard Billings, who taught Latin, led the choir,

coached football, and shepherded the Groton Missionary Society. Billings

had been a Harvard classmate of Theodore Roosevelt, A.B. 1880, governor

of New York, Spanish War hero, and Frank Roosevelt's fifth cousin.

Writing in May 1900, he advised College officials that

F.D. Roosevelt is a fellow of exceptional ability and

high character. He is mature in his aims and will get a great deal

from his courses. He hopes to go into public life, and will shape his work

at Cambridge with that end in view. I expect him to be a very useful member

of society at Harvard.

|

The senior board of the Harvard Crimson in 1904, FDR presiding. Photograph courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, tinted by Jim Gipe

|

Roosevelt and Brown were among 18 Grotonians in the entering class of 1904,

which initially had 537 members. A slender six-footer with patrician features

and an engaging smile, Frank Roosevelt had begun wearing pince-nez glasses

like his famous cousin TR's. He was good at golf, so-so at tennis, and too

light for football, TR's favorite contact sport and the one that mattered

most in the turn-of-the-century culture of masculinity. With 150 others

Frank tried out for freshman football, but was cut and assigned to the Missing

Links, lightest of eight intramural "scrub" teams. His teammates

elected him captain. "It is the only [team] composed wholly of Freshmen,"

he wrote to his parents, "and I am the only Freshman Captain."

Having done well enough on his entrance exams to earn sophomore standing,

Frank took six courses per term, the maximum number permitted, in order

to meet the requirements for the A.B. in three years (a practice followed

by more than a third of the undergraduates of the time). He majored in history

and got "gentleman's C's"-worth high B's by today's standards-in

almost all his courses.

His teachers in history and government classes included Edward Channing,

Archibald Cary Coolidge, Silas Macvane, Hiram Bingham (then a doctoral student,

later the discoverer of Machu Picchu), and Abbott Lawrence Lowell. His instructors

in public-speaking courses were Irvah Winter and assistant professor George

Pierce Baker. Le Baron Russell Briggs, George Lyman Kittredge, Pierre la

Rose, and Barrett Wendell were among his English teachers. Twice he took

undemanding geology courses given by the colorful Nathaniel Southgate Shaler,

dean of the Lawrence Scientific School. In his third year he took Fine

Arts 4 (medieval and Renaissance art) and enrolled in Josiah Royce's Philosophy

1a. He soon dropped it. "The appeal of systematic or abstract thought,"

one biographer has observed, "remained a mystery to Franklin Roosevelt

all his life."(see footnote 1)

Frank Roosevelt at Harvard, continued. Also see Roosevelts at Harvard, and "Roosevelt History Month"

Main Menu ·

Search ·Current

Issue ·Contact ·Archives

·Centennial ·Letters

to the Editor ·FAQs

A fortnight later the Alumni Bulletin published tributes from five

distinguished alumni. Older readers contributed reminiscences of his undergraduate

days. But the surprising fact is that no lasting memorial to Franklin Delano

Roosevelt was ever established at Harvard.

A fortnight later the Alumni Bulletin published tributes from five

distinguished alumni. Older readers contributed reminiscences of his undergraduate

days. But the surprising fact is that no lasting memorial to Franklin Delano

Roosevelt was ever established at Harvard.