Main Menu · Search · Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

Frank Roosevelt and Jake Brown were probably there when President Charles

William Eliot spoke at a Sanders Theatre reception for incoming students

in October 1900. "It is a common error," Eliot told the newcomers,

"to suppose that the men of this University live in rooms the walls

of which are covered with embossed leather; that they have at hand every

luxury of modern life. As a matter of fact, there are but few such. The

great majority are of moderate means; and it is this diversity of condition

that makes the experience of meeting men here so valuable."

Frank Roosevelt had already declared his intention of acquiring "a

large acquaintance," but it would not be as diverse as President Eliot

might have wished. His freshman social life revolved around luncheons, teas,

dinners, and dances in Boston and Cambridge. In College affairs he was resolved

to be "always active." He competed (at first unsuccessfully)

for the Crimson news board. He sang with the Freshman Glee Club and

became its secretary. Though the Hyde Park side of the Roosevelt family

normally voted Democratic, he joined the Republican Club to support his

Oyster Bay cousin Theodore, President William McKinley's running mate in

the election of 1900. In red caps and gowns, Frank and most of the freshman

class joined a torchlight parade into Boston to celebrate the Republican

victory in November. Sporting his pince-nez and spouting "Bully!",

Frank seemed to some of his classmates to be trading too much on familial

ties. A few started calling him "Kermit," after one of the Rough

Rider's preadolescent sons.(see footnote 2)

Frank had been at Harvard for less than a month when his 72-year-old father

had a heart attack. James Roosevelt had been ill with heart trouble for

10 years. His attack came two days after news of a scandal involving the

erratic "Taddy" Roosevelt, James's grandson by his first

marriage. Taddy had been a year ahead of Frank at Groton. He had great expectations:

his mother had come from the wealthiest family in America, the Astors. After

a troubled

|

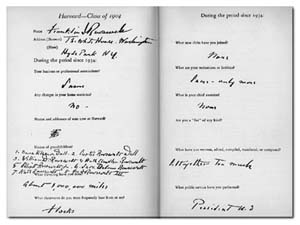

| Twenty years later, FDR sent in this information for the thirty-fifth reunion book. Photograph courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library |

As my Mother is all alone and as the end of the term is so near, I feel sure that you will not mind my staying at home with her. Also I should have to be here on Dec. 20th for some legal matter and I think I can make up during the holidays the work I am losing now. I shall be in Cambridge however on Wednesday next and if you desire to see me that day I can go to see you. I know you will understand that I am staying away merely for my Mother's sake and hope to have the work made up when we return early in January.

Believe me

Sincerely yours,

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The new president was interested in his cousin Franklin. He had encouraged

him during his years at Groton and Harvard; in 1905 he would give the bride

away at the wedding of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. "I'm so fond

of that boy, I'd be shot for him," he once told Sara Delano Roosevelt.

The admiration was mutual. In letters to her son, Sara referred to TR as

"your noble kinsman." Exposure to his ebullient relative always

quickened Frank's political hopes. But as a second-year student at Harvard,

he hoped most of all to follow TR as a member of the Porcellian Club.

The Porcellian was the loftiest of Harvard's "final" clubs.

The selection process was rigidly hierarchical. First you had to get into

the Institute of 1770, the oldest and largest club. If you were among the

first 70 or 80 of the 100 sophomores accepted, you were taken into

Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity ("the Dickey"). Then you might

join a "waiting" club, and at last a final club like Porcellian

or A.D. Your chances improved if you were a "legacy," i.e., related

to a member.

The Porcellian was the loftiest of Harvard's "final" clubs.

The selection process was rigidly hierarchical. First you had to get into

the Institute of 1770, the oldest and largest club. If you were among the

first 70 or 80 of the 100 sophomores accepted, you were taken into

Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity ("the Dickey"). Then you might

join a "waiting" club, and at last a final club like Porcellian

or A.D. Your chances improved if you were a "legacy," i.e., related

to a member.

By Christmas of 1901 the Institute of 1770 had elected 50 men. Frank Roosevelt

wasn't one of them. His anxious thoughts were diverted by an invitation

to the social event of the season-17-year-old Alice Roosevelt's coming-out

party at the White House. Two days after Christmas, Frank wrote Dean Briggs,

I have been asked to a dance at the White House in Washington on Friday January 3rd. As I have only three recitations on Friday, and none on Saturday, do you think I might go to it? It would be very kind of you to let me know about it.

By then Frank was thinking about life after Harvard. He had run unsuccessfully

for class marshal, finishing fourth in a field of six. (The clubs,

he thought, had conspired to elect their own three-man slate.) He then ran

for class committee chairman and chalked up an electoral victory. Now he

had to choose a law school. He had meant to attend Harvard Law, but his

mother wanted him closer to home and was urging him to enroll at Columbia.

To his mother's dismay, he intended to marry. He and Eleanor Roosevelt,

TR's "favorite niece," had been distantly acquainted since childhood.

They had been seeing each other regularly since November 1902, when they

met at the New York Horse Show. Eleanor visited Frank and his mother at

Campobello the following fall. In November she was his guest at the Harvard-Yale

football game. The next day they went walking in Groton and Frank proposed.

He was then 21; Eleanor was 18.

He broke the news to his mother at Thanksgiving. She first asked that

the engagement be kept secret for a year. Later she told Frank that she

would be renting a Boston apartment that winter, as she had for the past

two years. Frank opposed this extension of motherly oversight. As an alternative

he suggested they take a five-week winter cruise to the West Indies,

with Lathrop Brown as their guest. Sara acquiesced. The separation from

Eleanor did not cool Frank's ardor. Sara tried vainly to get him a post

as ambassadorial secretary at the Court of St. James's, where both his father

and half-brother had served. In time she became reconciled to the marriage,

but she also contrived to retain a controlling interest in her son's personal

life.

Frank was graduated from Harvard on June 29. As class committee chairman

he got to sit on the Sanders Theatre stage. Sara and Eleanor were in the

audience. The class orator was Arthur Ballantine, a man Frank had beaten

out for the presidency of the Crimson. "Our freedom must be made a

means of service," declared Ballantine. "Some, catching a bit

of the spirit of our brothers Phillips, Sumner, and Roosevelt, will find

their chance in the field of politics and social reform. Others, perhaps,

may help to lift American literature back to that high plane to which it

was once led by a Cambridge group. Wherever we serve, the message of this

ancient University is clear: we are to stand for absolute freedom of thought."

The Roosevelt he had in mind was, of course, TR. But FDR would find

his chance when it came.