Main Menu ·

Search ·Current

Issue ·Contact ·Archives

·Centennial ·Letters

to the Editor ·FAQs

Check out the athletic department's schedule listing for updated sports information.

|

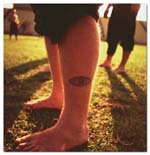

Senior halfback Eion Hu ran for 118 yards in the season's opening game, a 20-13 overtime loss to Columbia. On his fourth carry, Hu broke Harvard's all-time career rushing record. Phtotgraph by Tim Morse

|

For the Record

Eion Hu now sets one with each yard he gains

"Put your enemy in the wrong-and keep him there" was the maxim

espoused by Samuel Adams, A.B. 1740, political agitator and life of the

Boston Tea Party. By and large, Harvard football teams of the past decade

have seemed unaware of it. This season's opening-game loss to Columbia was

a case in point. Chiefly because of the footwork of halfback Eion Hu '97--who

broke a school rushing record in the second quarter--the Crimson had the

Lions down 13-0 at the half. But turnovers and a bungled field goal try

in the final quarter let Columbia tie the game, which then went into overtime

(a mandatory requirement, alas, in Division I-A and I-AA college football

this fall). The outcome was settled swiftly. Columbia scored on its first

possession, came up with an interception when Harvard was given the ball,

and was duly credited with a 20-13 victory.

"It never should have gotten to overtime," said Harvard coach

Tim Murphy. "We had our foot on their throats a good part of the game

and we didn't finish them off."

Hu's big day was the bright spot for Harvard followers. The rest of the

action was ruled by turnovers. A weak Columbia punt, a misdirected pass,

and a fumble gave Harvard a pair of field goals and a touchdown in the second

period. A Harvard fumble and three interceptions let the Lions out of their

cage in the second half. They caught up with a touchdown and two fourth-period

field goals, the second a 48-yarder that dinged the crossbar and tied the

game.

Hu promptly responded with a 52-yard breakaway run that took Harvard deep

into Lion country. The Crimson advanced to the one-yard line, then got hit

with a five-yard delay-of-game penalty that prompted coach Murphy to opt

for what looked like an easy field goal, with 1:36 on the clock. But the

snap from center was high, and the kick was blocked by Marcellus Wiley,

the Lions' behemoth defensive end. Harvard came away empty-handed, and the

5,760 in attendance had the novel experience of witnessing an Ivy League

tie-breaker. Columbia, an opening-game pushover for almost 20 years, has

now beaten Harvard twice in a row-for the first time since the early 1950s.

Tim Fleiszer '98, a converted fullback, played a strong game at defensive

end. Jay Snowden, another junior, started his first game at quarterback.

He completed 10 of 24 passes and had three picked off. He also punted, but

his work was subpar: seven kicks, 27-yard average. Freshman Chris Menick

made a promising debut at halfback: 25 carries, 91 yards. Ryan Korinke '99,

who made good on four out of seven field goals a year ago, handled the place-kicking,

nailing two of three field goal attempts and a point-after.

Hu scored the team's only touchdown on a six-yard carry. It was his twenty-first

in 20 varsity games (his class was the last to participate in freshman football).

Nursing a hamstring injury sustained in preseason practice, Hu was not at

full strength. Even so, he came off the field with 118 yards rushing and

a career total of 2,230 yards. On his fourth carry he eclipsed the career

record of 2,130 yards set in 1968 by Vic Gatto '69. Hu now breaks his own

record with each yard he gains, but after the overtime loss to Columbia

he was inconsolable. "The record doesn't mean anything to me,"

he said at a postgame press conference. "Today was terrible. I missed

two blocks and fumbled."

Hu came through the next weekend, scoring twice and rushing for 113 yards

as Harvard rocked Bucknell, 30-7. But the day's most spectacular effort

came from the Crimson defensive unit. Its members held the Bison offense

to minus 4 yards rushing and sacked quarterback Jim Fox five times. Rich

Lemon, Bucknell's all-time leading rusher, finished the game with 12 carries

and minus 9 yards.In its home opener a week later, Harvard lost a hard-fought

contest to Lafayette, 17-7. The Leopard defenders employed an eight-man

line to put pressure on Snowden, and Harvard couldn't mount a consistent

passing attack. Still nursing his muscle pull, Hu gained 69 hard-earned

yards. Snowden, a strong runner, scored Harvard's only touchdown on a 32-yard

keeper.

Golden oldies: The Great Gatto's 28-year-old rushing record, now

eclipsed, dates from the finale of the 1968 season, when unbeaten Harvard

scored 16 points in the last 42 seconds to tie Yale, 29-29. Gatto pulled

a hamstring and played only in spots, but it was he who caught Frank Champi's

last-gasp touchdown pass as time expired. In those days a tie really meant

something.

Hard times: From 1991 to 1995, Harvard teams had an overall won-lost-tied

record of 16-33-1, the poorest for any comparable period since the early

1950s. Only the squads of 1949 (1-8) and 1950 (1-7)-when Harvard's governors

began thinking about dropping football-posted sorrier records than last

year's (2-8).

Enfin: The 1996 squad has its merits-aggressive defensive crew, fine

receivers, Eion Hu. But the start of this fall's campaign made it clear

that the passing attack and the kicking game needed lots of attention, and

that coach Murphy's young team still had much to learn about keeping the

enemy at bay. A crash course on the theories of Samuel Adams might help.

Harvard's soccer teams had fun at Columbia. Both posted decisive victories:

4-1 for the men's team, 3-0 for the women's. All-American Emily Stauffer

'98, Kristen Bowes '98, and Naomi Miller '99 scored for the women's team.

In the men's game Rich Wilmot, a big senior forward, put in two of the goals;

John Vrionis '97 and Tom McLaughlin '98 got the others. Speedy Kevin Silva

'97, sidelined last year by a leg injury, contributed two assists. Jordan

Dupuis '99, a New Zealander, split the goalkeeping duties with veteran Peter

Albers '97. Harvard had opened its season with a 3-1 loss to Cornell, the

defending Ivy League champions.

The men didn't look ready for prime time against Cornell, but the Columbia

match was the takeoff point for the longest winning streak enjoyed by the

men's team since the Ivy championship season of 1987. Victims included nationally

ranked Boston University (2-1), Yale (4-3, overtime), Central Connecticut

(3-0), Lafayette (3-0), and Pennsylvania (2-0). Four stellar veterans from

the Greater Philadelphia area-captain Will Kohler '97, T.J. Carella '97,

McLaughlin, and Silva-made the most of their road trip to Pennsylvania.

Kohler and Carella each had a goal and an assist at Lafayette; Carella's

penalty kick gave Harvard an early lead over Penn, and Silva put in the

insurance goal on a pass from McLaughlin.

Fast competition: The field hockey team posted a 1-0 victory over

William and Mary in a September tournament hosted by Duke University. Duke's

roundballers had edged Harvard, 2-1, the previous day. . . . In men's water

polo, Mike Zimmerman '99 popped in five goals as Harvard posted a 17-5 victory

over Washington and Lee at a Naval Academy tournament. He'd scored four

as Harvard lost to the Middies, 12-7, a day earlier. . . . When the women's

volleyball team was shut out, 3-0, by George Washington University, its

record fell to 1-5. But hey, the season is young yet. -"Cleat"

Beautiful Feet

|

The Merlin of midfield: soccer genius Emily Stauffer in action. Photograph by Tim Morse

|

The fact that Michael Jordan also wears number 23 is only coincidence; Emily

Stauffer '98 chose that number to celebrate her birthday, June 23. But Stauffer's

dazzling dexterity with a soccer ball does occasionally suggest Jordan's

talent with a slightly larger sphere. "She's just magic," says

her coach, Tim Wheaton. "Emily can make that ball do whatever she wants."

A First Team All-American last year, Stauffer is clearly one of the most gifted

athletes ever to head a ball on Ohiri Field. After four games this fall,

she had netted five goals and two assists, including a three-goal outburst

in the first half against Boston College. On the first of those,

Stauffer took a pass from Rebe Glass '98 and then ran a solo aria against

one overmatched defender; the score had an artful elegance. What's more,

Stauffer now exercises her genius amid a sparkling array of teammates, and

the Harvard side has become a formidable power in women's soccer.

Undefeated Ivy League champions last fall, Harvard nonetheless received

no bid to the NCAA tournament. Why? Some felt the schedule needed toughening.

So this year, Harvard has scheduled the University of Hartford, a top-20

team last fall, and the University of Connecticut, a top-5 side. On their

way to those contests, the Crimson began the season by knocking off New Hampshire

(2-1), Columbia (3-0), Boston College (4-1), and Yale (2-1).

The Bulldogs were the most tenacious of those opponents. Yale took a 1-0

lead by the half, using an effective if tedious strategy of clogging the midfield

with bodies. But in the second stanza Harvard spread out the slower, less-nimble

women from Yale and played most of the game in Yale's end. Yet frustrations

continued; overall, Harvard took 26 shots to Yale's seven. At one point,

the powerful, dangerous forward Keren Gudeman '98 nearly broke the crossbar

with a rocket that bounced out, not in. Finally, with about 14 minutes left,

freshman Gina Foster found the net to tie the score at 1-1 and the crowd

at Ohiri erupted, releasing more than an hour of pent-up tension. Then Harvard

kept pressuring Yale; in a breathtaking finish, quicksilver forward

Naomi Miller '99 blasted a left-footer past the Yale goalie for the winning

score, with only 11 seconds left on the clock.

In addition to Stauffer, Miller, and Gudeman, Dana Tenser '97, Kristen Bowes

'98, and Devon Bingham '99 are all serious scoring threats. A measure of

Harvard's overwhelming offense: after four games, the team had outshot its

opponents 95 to 17, more than 5 to 1. Goalkeepers Jennifer Burney '99 and

Anne Browning '00 were becoming the Maytag women of Ohiri Field, with only

nine saves between them over the first four contests. Even so, Wheaton's

priority is to move the entire defensive effort up a notch. Add that to Harvard's

awesome firepower, and there's no telling how far these women could

go.

Team Transcripts

|

Offensive lineman Matt Birk '98 exposes his loyalties in Vanity Fair. Photograph by Peggy Sirota for Vanity Fair

|

In September, Vanity Fair magazine revived an old tradition of spotlighting

Ivy League football players by printing a group photograph of gridiron stars

from each of the Ancient Eight. Harvard's representatives were Eion Hu '97

(see page 70) and Matt Birk '98. In September, Burger King named Hu, an

economics concentrator, its "Scholar-Athlete of the Week," and

donated $10,000 to Harvard's general scholarship fund in his name.

Although Hu may exemplify the scholar-athlete, some of the best sports prospects

in secondary schools look less impressive on the transcript than on the

field. To ensure that Ivy League sports teams represent their schools

academically as well as athletically, the League in the early 1980s formulated

a guideline known as the "academic index," using a statistic called

the standard deviation, which measures the degree of variability or dispersion

in a population. "The idea was that, if you put all athletes together,

they'd be within one standard deviation of the class average," says

dean of admissions and financial aid William Fitzsimmons '67, Ed.D.

'71. "We did not want a separate athlete population."

The index uses Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores, class rank information,

and achievement test scores to compute benchmarks for each class, and a

rolling average for the four classes in college at any one time. Each of

the three components contributes up to 80 points to the total. A freshman

whose standardized test scores were all 800s and who ranked first in

a class of 2,000 would score the maximum of 240 on the academic index. The

Ivies impose a "fioor" of 169 for all recruits. As a general

rule, the group of recruited athletes within each sport must fall within

one standard deviation of their college's academic index.

The rub--at least for some coaches--is that different colleges have

different academic benchmarks, so the Ivy playing field is not level

in terms of recruiting. In index terms, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton are

at the top of the league (with Harvard atop that triumvirate), confining

H-Y-P coaches to a more academically rarefied group of athletes. Carolyn

Campbell, senior associate director of the Ivy League office, explains that,

unlike the case with intercollegiate sports competition, "Students

at different colleges don't compete with each other academically. Scholastically,

Harvard students compete with other Harvard students, not with Penn students."

Yale football coach Carmen Cozza, now in his final season, has publicly

declared his opposition to the academic index. Tim Murphy, his counterpart

at Harvard, declines to comment, as does Harvard athletic director Bill

Cleary '56. But in terms of recruiting athletes, the index is widely perceived

to favor schools with lower numbers--Penn, Columbia, and Brown. Even so,

Princeton last year won the Ivies in football, and captured 10 more league

championships-the most any member college had amassed in the league's 40-year

history.

Factors like "early decision" admissions-which Princeton and Yale

began last year-complicate the recruitment scenario. Early decision commits

students to the college that has accepted them by December of their senior

year. Harvard and Brown offer "early action," which assures an

applicant of admission but allows applications to other schools to go forward,

with the student choosing a college in the spring of senior year. Differences

in yield-the percentage of those accepted who enroll-also play a part. Harvard's

yield is generally the highest of any college; for the class of 2000, it

was an extraordinary 78 percent.

What this means in practical terms is that if Harvard can successfully recruit

an athlete who gains admission, there is an excellent chance of that athlete

playing for the Crimson. Fitzsimmons notes that there's a sequential process:

after being recruited, you have to apply, be accepted, and matriculate.

Then you have a chance to make the team. How successful that team

is in Ivy competition--in, say, football--is another matter. At Yale, openly,

and at Harvard, quietly, it's this last question that's being talked about

in athletic circles.

Main Menu ·

Search ·Current

Issue ·Contact ·Archives

·Centennial ·Letters

to the Editor ·FAQs

![]()

![]()